Oleg Kulik: Through the Bars with Gritted Teeth

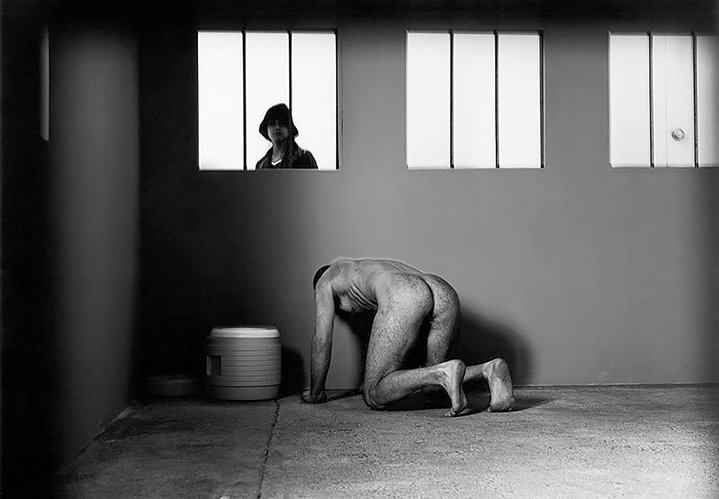

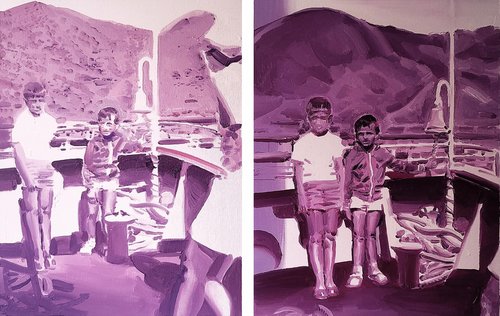

Oleg Kulik. Anima Animalis, 2023. Exhibition view at Diehl Gallery. Courtesy of Diehl Gallery

Radical artist best loved for his ‘man-dog’ performances is currently under trial in Russia for offending the authorities in the wake of new anti-dissidence laws. While he awaits trial, a solo show has opened at Berlin’s Diehl Gallery.

Bringing together some of the artist’s earliest works, such as his ‘Deep into Russia’ series of the nineties shown along with more recent pieces, a new exhibition at Diehl in Berlin curated by Carsten Ahrens, functions on a juxtaposition of the old and new. And it is his works from the most notorious and infamous ‘dog’ period which act as the glue holding it all together. Among various photographic series of the decade on view, there are the video documentations of his two most iconic performances, ‘I love Europe, It Does Not Love Me Back’ at Bethanien in Berlin in 1996 and the following year ‘I Bite America and America Bites Me’, at Deitch Projects in New York.

Taken as a whole, the exhibition presents Kulik’s career as a path of radical derision mixed with love and a striving for self-liberation. Transgression is an integral part of his path.

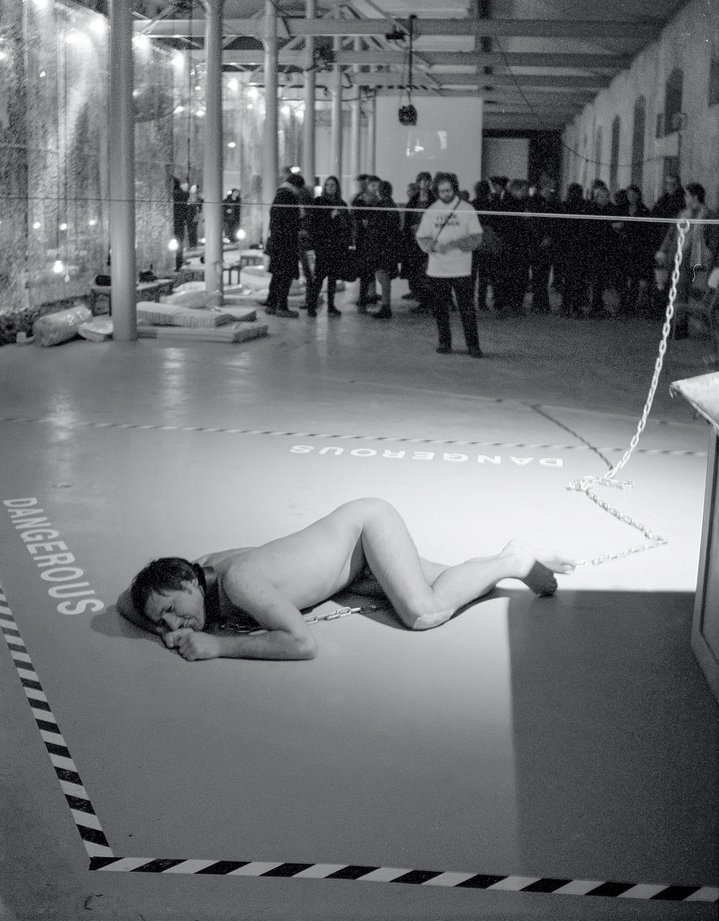

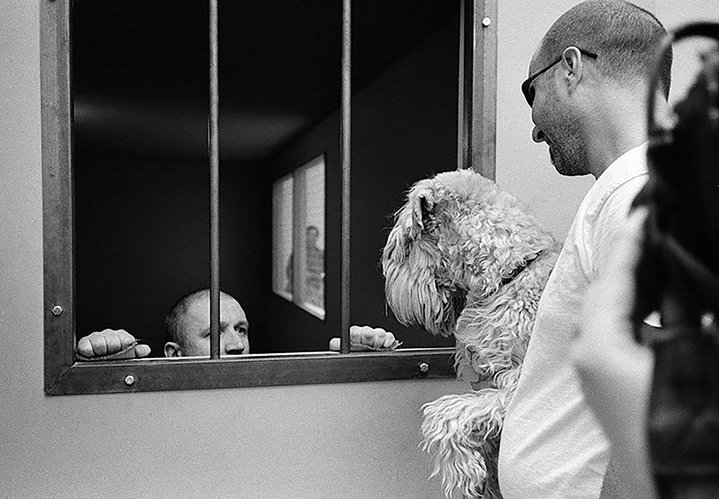

Oleg Kulik. I Bite America and America Bites Me (Series of 23, #12), 1997. Courtesy of Diehl Gallery

Born in Kyiv, Ukraine in 1961, Oleg Kulik has lived in Moscow for the most of his life and is internationally perceived as a Russian performance artist. His artistic origins do not betray any of the enfant terrible he later became. Initially Kulik trained as a sculptor and then worked as the artistic director of Regina, one of Moscow’s first commercial galleries from 1990 till 1993. Those three years in which he worked as a curator coincided with the end of the USSR, the Communist party was still in power. However, back in 1990 its influence was already waning, and small-scale private businesses were already becoming commonplace. And simultaneously, the USSR was opening up to the world, its art sparking international interest, such as in Sotheby’s now legendary auction in Moscow in 1988. Late Soviet contemporary art became popular in Europe and the US, and collectors and curators come to visit Russia.

However, by 1993 the situation could not have been more different. The USSR had dissolved, followed by production line interruptions, resulting in the breakdown of industry and huge unemployment throughout most of the resulting fifteen new states. In the art world, international interest in these aspiring democracies was fast on the wane, and sales eventually dried up. Yet in many ways, this widespread social, economic and political depression acted as a stimulus for Russia’s artists who needed to survive and at the same time had unprecedented freedoms. It was just at this crucial time that Oleg Kulik lost his curatorial job at the gallery.

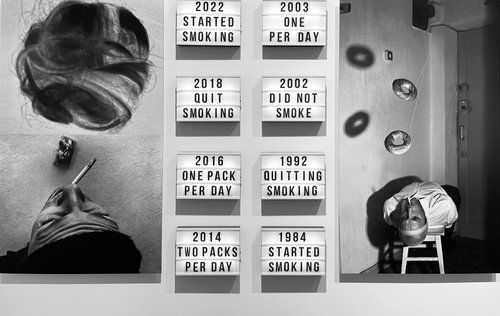

The earliest work shown at the Berlin exhibition dates from this period. It is a black and white series of twenty-nine photos called ‘Deep into Russia’ which he made in 1993. It starts as a ‘harsh but true’ documentary but quickly evolves into something quite different: a fake-glamorous, fake-pornographic, fake-zoophilic mocumentary. Kulik goes for the jugular, ridiculing and exaggerating at the same time contemporary glossy publications and the seriousness of traditional documentaries.

It was as early as 1994 that Kulik found his alter-ego as a ‘man dog’. It was as if the times were such that the only way to express yourself was to become rabid, to bite and drool. His performance ‘The Mad Dog or Last Taboo Guarded by a Lone Cerberus’ which took place on 23rd of November 1994, involved artist Alexander Brener (b.1957) walking him on a leash. It became a symbol of the epoch. Oleg Kulik’s emergence as a performance artist also marked his transgression into the wider world, and he became the most famous post-Soviet artist of the time. While in Russia his performance works were quite varied, including the 1994 ‘New Sermon’ and the 1995 ‘Political Animal’ a.k.a ‘Kulik for President’, it was for his dog persona that he became noticed internationally.

He began to push the boundaries. In 1995 Kulik was arrested in Zurich for his non-sanctioned actions at the opening of a group show of blue-chip artists, where he barred visitors from entering the venue. And by March 1996 he was an institutionalized member of the ‘Interpol’ group exhibition in Stockholm, where as a dog he physically assaulted visitors and destroyed some of the artwork on view. Again he was arrested.

His 1997 endurance performance in the USA, ‘I Bite America and America Bites Me’ directly references Joseph Beuys' (1921–1986) famous ‘I Like America and America Likes Me’ performance with a coyote at the René Block Gallery in New York. Kulik spent two weeks in a cell where he attacked visitors. One of the most striking images in the current show is the artist looking straight into camera from behind the bars.

In 1999 times had changed again in Russia, and Regina gallery opened once more in Moscow with an inaugural exhibition, ‘Russian’ by Oleg Kulik, by that time a celebrity artist both inside Russia and abroad. Throughout the noughties he built on his international success, mostly turning to photography, sculpture and installation. His large-scale sculpture ‘Tennis Player’, 2002, was shown at the Venice Biennale.

In 2007 he enjoyed a large retrospective exhibition at the House of Artists in Moscow, co-produced by MMOMA and XL Projects, and curated by Elena Selina. This show preceded the highly successful ‘I Believe!’ group exhibition at Vinzavod Art in Moscow which was curated by Oleg Kulik himself.

After a long hiatus, Oleg Kulik made a come-back in 2018 and presented a new body of work called ‘Our Mother’ as the inaugural show for the Scene gallery in Moscow. His new preferred materials were synthetic foam and iron bars. After Russian troops entered Ukraine in 2022, one of the works from this show came to the attention of the Russian authorities, who subsequently took legal action against the artist. It was the sculpture ‘Big Mother’, he had made four years previously which was being exhibited in April 2022 at Art Moscow fair. It was only two months after the hostilities had broken out and new laws had just been rushed through incriminating dissidence with the military actions of the state leading to a witch hunt by governmental loyalists. The artist was accused of ridiculing soviet-era war monuments which brought a criminal charge. “If even ten per cent of the interpretation that is now being projected onto my work was true, I not only would not show it, but I also wouldn’t even have started making it,” he said in an interview to The Art Newspaper Russia, explaining that the sculpture was a reaction to personal rather than political issues. “It took almost three years to make and was a painful recovery from the trauma of being separated from my beloved wife.”

The ’Grid’ pieces made in 2019 and now on show at Diehl are made of steel and naturalistically sculpted body parts, which squeeze through the grilles. Once more the artist is turning to transgression as his modus operandi, a recurrent motif whose radical irony is a threat to the artist himself.

Sadly, this exhibition is the last for the curator Carsten Ahrens, who passed away just weeks before opening.