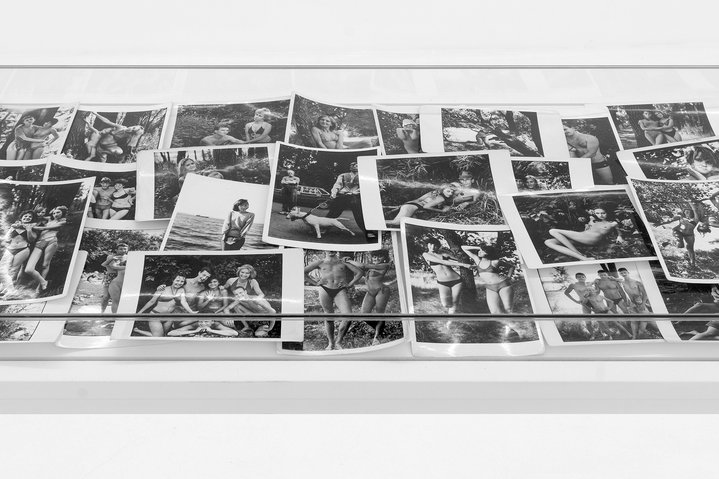

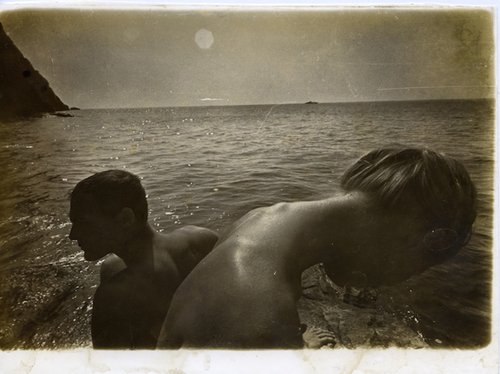

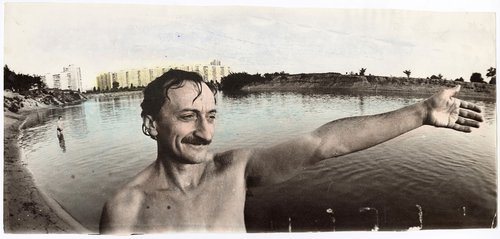

Nikolay Bakharev. Exhibition view in the Szena Gallery. Courtesy of Szena Gallery

Nikolay Bakharev on why the city is not a garden

A picture should not be beautiful, but interesting. Then you can find beauty. Beauty is in the human relationships that are formed’, so said Nikolay Bakharev evoking the emotional power behind his photographs of the secret life of the Soviet working class, now on view in Moscow.

‘There will be a garden city here’, promised Vladimir Mayakovsky in his 1929 poem ‘Khrenov's Tale of Kuznetskstroy and the People of Kuznetsk’. Today the city of Novokuznetsk is large with more than half a million people, but his garden prophesy was off the mark. In fact, Novokuznetsk is one of the ten dirtiest cities in Russia, as well as one of the five oldest in Siberia, at least among those that still exist. And Nikolay Bakharev (b. 1946)’s images are not of smog or antiquities. It is people he is most interested in and that is the secret of his success: incredible sociability.

‘What kind of artist am I?’ – Nikolay asks me rhetorically, sitting in his room at the Marriott Grand in Moscow before the opening of his new exhibition at the Szena Gallery, ‘can I even think of such a thing?’ The artist had just arrived from Novosibirsk, after attending the All-Russian Week of Young Photography fair where he had been speaking to a whole new generation, ‘Flusser says photography is a programme. And there is randomness in it. I take 50 to 60 shots. If I get one result, it's an accident”.

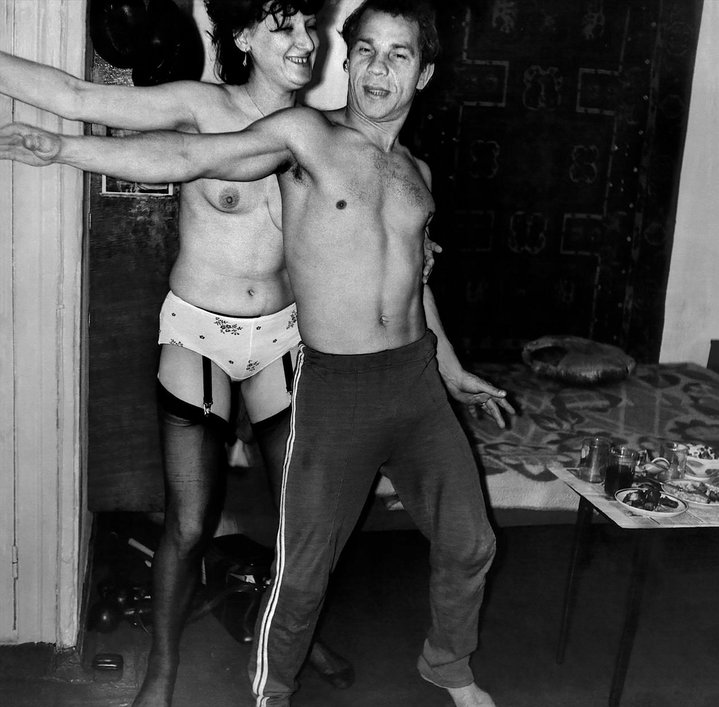

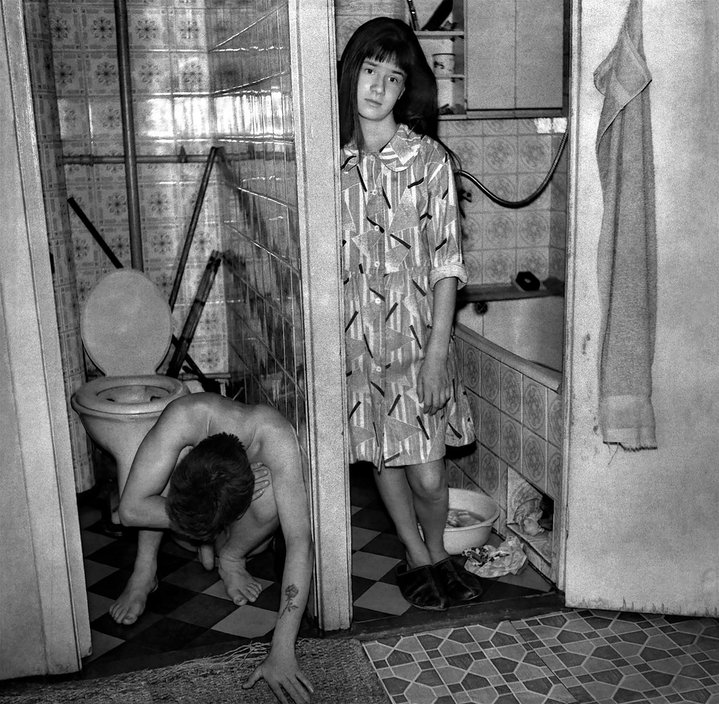

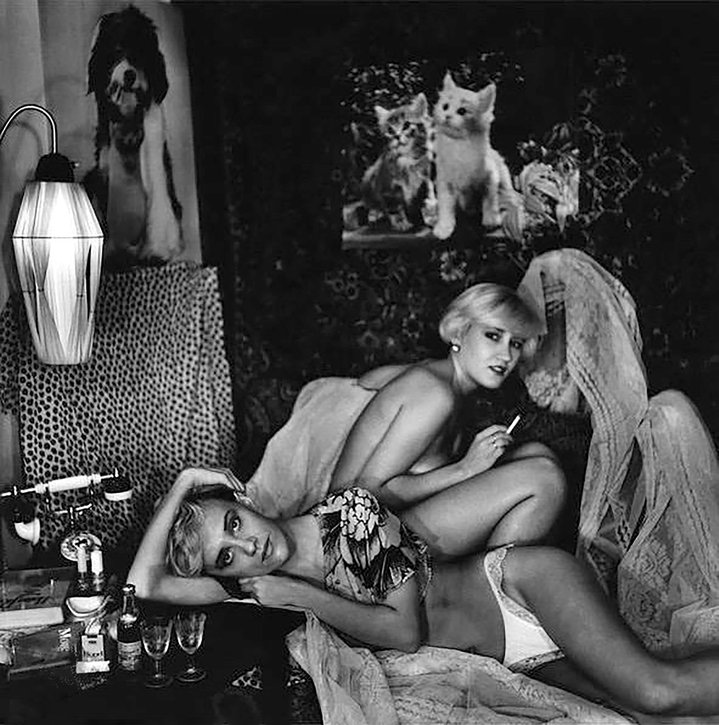

The people in Bakharev's works all look of a certain type. When they pose for the camera, they don’t look comfortable, but have dignity. When they get undressed, they look natural. Nudity is Bakharev’s signature. Whether his protagonists are depicted in their underwear or without it, in front of the camera they act as though there is no one looking. It’s almost as if they were taking selfies before the selfies’ era. His models are chiefly working women, students, or residents of poor suburbs.

He identifies with his subjects. ‘I'm just like them, so what they like, I like’, explains the artist. Orphanage scion Nikolay Bakharev made a spectacular rise within just a few years to become a fifth-class locksmith at the Kuznetsky Iron and Steel Works (the highest qualification for a repair worker in the Soviet Union was the sixth). He was in the upper ranks of the Soviet working class, with a stable wage and some social standing, when during the stagnation of the Brezhnev years, he decided to walk away from the factory to become a photographer.

Communist ideology dictated that the working class had the leading position in society. But there was no one who would have photographed the working class from the perspective of the working class: in Soviet documentary photography it was always seen through the eyes of the Other. However, unusually, Bakharev came from within the ranks: ‘I was there as if a servant. In front of a servant, so you can show yourself. Over time I realized that I was just the same as them.’

‘In the [Soviet] domestic service I learned to do relatively good quality work under all conditions,’ he explained. Domestic service units (DSU) in the late Soviet Union were multifunctional centres giving services which ranged from laundry to watch repair. ‘I brought in money, and so I was useful. I photographed kindergartens, weddings, funerals. And people on the beach. All schools in the cities had their own photographers so I went to villages. Who would go to villages then?”. The DSU gave him chemicals, film, and some legal cover. Then he went to work for the Khudfond (Art Fund) photographing paintings there and continuing to do independent work on the beach and in private interiors. In fact, during perestroika, he became best known for his beach scenes and intimate images of Soviet life.

‘A client never commissions material made for an art exhibition. People want to be photographed for their own reasons; they do what they want. I can provoke them, but I can't make up a relationship. The idea must come from them. For me, I have to get it right. If I did what I wanted to do no one would pay me’, the author recalls his years of work. He has developed a special ethic, based on a relationship of trust with his clients: ‘I design an interior, condense, and shoot it: I can play about a bit with what there is in the interior. There must be a mutual relationship, they need to understand that I am not watching my sitters, it’s as if I’m part of the picture and I am not the author of the shoot’. Nikolay Bakharev believes that the best results happen if ‘I am enjoying myself in the process everything comes together. It’s as if am them, even if I have my professional hat on’.

During the Soviet times private photographers made a lot of money and were hated by reporters who were the professional elite. Bakharev himself did not accept the Soviet press and its quaint incongruous maxim, ‘Ah, linger on, thou art so fair!’. ‘It didn't correspond to what I encountered in my life. And it made me skeptical about journalism’.

Then there were the many technical limitations which determined the style of his images. Film was in black and white, 100-200 ISO, the shutter speed needed for the interiors was half a second or a quarter of a second, and he shot images on a tripod. It meant his sitters could not move but they had to look lively and engaged at the same time, or the shot would fail. Of his method and sitters, Bakharev says, ‘I take them out of three-dimensional space into two-dimensional space and the pose has to be convincing which is not easy for people to grasp’.

Nikolay Bakharev first started taking pictures in a children’s photo studio in his orphanage using a plastic Smena camera. In 1965, he bought his very first camera on his worker’s salary, and then throughout his life he struggled with FotoCorr, Iskra, Kiev-60: all of them were amateur or semi-professional Soviet gadgets which were not easy to shoot due to their low technical quality. His photoshoots in an interior could last between three and five hours, a session with just one model on the beach could take only five minutes, but there might have been fifty such shoots to do in one weekend. It was a job that had nothing to do with art, but gradually he would take his own shots, which he kept for his own series.

‘You press a button, and the result is a stereotype. We are surrounded by borrowed imagery. Only a few people manage to go further,’ admits Bakharev, ‘An artist works with stereotypes and asks how to get away from them. You can't escape them. However, by accident I happen to get some shots that I feel don't depend on me’.

Soviet amateur photographers supported one another in dedicated photography clubs. But ‘Nudity was not accepted at the club in the Soviet times as it was seen as pornography. You could take pictures, and you couldn't exhibit them,’ Nikolai recalls, ‘and only the artistic director of the Novator clubs, Geogry Kolosov would stand up and defend me, he openly said those Moscow clubs were behind the times’. From the 1960s to the 1980s, Novator was considered the top photography club in Moscow.

‘The Siberia club in Novokuznetsk was one of the best in the country. They couldn't accept me because I was working at the domestic service unit. They saw photography as an ideological organ. As propaganda’. Nonconformists, members of the Triva Club also in Novokuznetsk, rejected Bakharev's work for other reasons: ‘you can't interfere in the historical process. They could not accept me in any way’. Nowadays they are often exhibited together: ‘But they are adherents of reportage photography. They didn't need those who made ‘staged’ photographs. They took their information from magazines which came from abroad’.

Openness is one of the ancient traits of the Siberian character. Brutality is another. Over just three days during the Russian civil war in 1919, the famous partisan Rogov killed all the ‘representatives of the propertied classes’ in the town of Kuznetsk. It turned out to be half the population: rich peasants, merchants and industrialists, officers and policemen, the nobility, and the clergy. Anyone without a blister on his or her hand was killed. They were hacked down with sabres, sawed off with saws. Churches were burned down, shops looted. But today, Bakharev takes photos of people who as he puts it are capable of ‘doing that all over again’. Brutality as the norm. You see it in the direct hard stare into the camera of his sitters, or in the cigarette poking out of the corner of someone’s mouth. The defenselessness of the working class, which is always a threat.

A breakthrough to authenticity is possible by stripping someone of everything that protects him or her. Nikolai Bakharev stood on the flip side of social realism. Soviet reportage imagined the man or woman eof duty. And Bakharev photographed the private lives of Siberians for themselves, not hiding their incessant drinking or rampant promiscuity. His approach during perestroika was given the nickname ‘Bakharevshchina’.

Novokuznetsk is an industrial city which was set up by the Soviets next to places devastated by Rogov the partisan. The Kuznetsk Metallurgical Works became a ‘giant of socialist industry’, the largest steelworks in Russia, and Novokuznetsk, which grew up around it, became a factory town. People from across the former empire went there less than a century ago, some looking for higher wages, others fleeing famine and collectivization. They married, had children, and those had children of their own, but tragically all together they didn't create any distinctive ‘local’ culture. Novokuznetsk is sadly a kind of characterless, non-place.

Yet Nikolay Bakharev still lives in Novokuznetsk. Despite his participation in the main project of the 55th Venice Biennale in 2013, a group exhibition at the New Museum in New York in 2011 and a nomination for the Deutsche Börse prize in 2015, he does not have a separate studio in his hometown. He has set up a small laboratory in a room in his own apartment. The local city authorities still view him as a suspected pornographer, and many of his works have never been shown in public and are unlikely to ever be published in Russia. But Anastasia Shavlokhova, founder and curator of the Szena Gallery, hopes to eventually catalogue and scan all of his pictures.

He is the last of the real outsiders. Nikolay Bakharev, a self-made photographer from Siberia, remains perhaps the last Soviet nonconformist that no one has yet been able to tame. ‘A picture should not be beautiful, but interesting. Then you can find beauty. Beauty is in the human relationships that are formed’, he adds as if by afterthought towards the end of our conversation.