Natalia Opaleva: birth of a museum

The story of how a single portrait by a long-dead homeless Russian artist turned a successful banker into the creator of a Moscow museum of non-conformist art

Art collecting is like gold prospecting. Just ask Natalia Opaleva, a banker and gold company investor who was drawn like a magnet to a painting by Anatoly Zverev, a Soviet underground artist whom she had not heard of before, when circling the stalls at a Moscow art fair in 2003.

Up until then, she says, “my entire sphere of interest was in the realm of finance,” but she had already decided that it was time to broaden her horizons.“I walked around once, twice, and then a third time and I kept coming back to this one portrait,” she said. “A very beautiful woman came up to me and said, ‘Let me tell you about this portrait.' The beauty revealed that she had been the model in that 1959 painting and explained that it was by Anatoly Zverev (1931-1986), a restless down-and-out who had spent his entire life in Moscow. Opaleva then bought that work for $5,000.

“Of course, when I bought this portrait, I couldn’t even imagine that it would lead to the opening of a museum.” The collection of her AZ Museum, opened in a central Moscow mansion in 2015 at a cost of $12.5 million, is primarily made up of works by Zverev. It now draws 45,000 visitors per year, and has become a visible presence in Moscow's cultural landscape. This March, Natalia Opaleva received The Art Newspaper Russia Award, in the Personality of the Year category. The beautiful woman in the Zverev portrait, Polina Lobachevskaya, is now the museum’s co-founder, curator and art director.

Aliki Costakis, daughter of the late Russia-born Greek collector George Costakis, who was a longtime patron of Zverev and dubbed him the “Russian Van Gogh,” was so taken with Opaleva’s interest in the quirky artist that she donated 600 of his works to the AZ Museum. Zverev was categorized as a “parasite” by Soviet authorities for not holding an official job. They harassed him for his entire adult life, especially when he became renowned abroad. It was only shortly before his death in 1986 that he held his first solo show.

The museum building is situated in the geographic heart of the artist’s Moscow haunts, where he went on his long drinking binges — and where he expressed his obsessive love for Oksana Aseyeva (1892-1985), a muse of the early 20th century Avant-Garde whom he first met in 1963. Zverev painted hundreds of portraits of this much older woman.

The museum’s mission does not stop at Zverev. From Aliki, Opaleva also purchased her father’s collection of Russian Non-Conformists that he was allowed to take out of the Soviet Union to Greece in the 1970s. As a result she now has a total of 2,500 works, of which 1,500 are Zverev's.

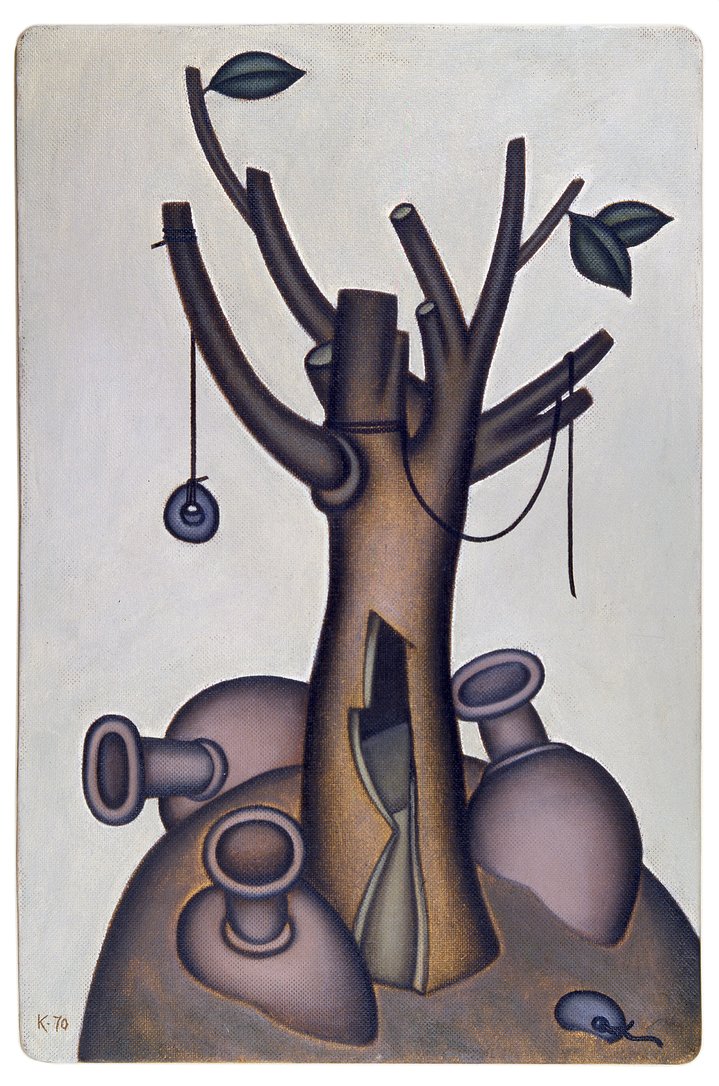

The rest include such artists as Pyotr Belenok (1938-1991), Lydia Masterkova (1927-2008), Vladimir Nemukhin (1925-2016), Dmitri Plavinsky (1937-2012), Oskar Rabin (1928-2018) and Oleg Tselkov (born 1934). “I bought some from collectors, some later at auctions and from artists’ families,” Opaleva said. “I was very lucky to be able to buy and gather a collection of very good works.” She now limits herself to about 100 new acquisitions annually.

Opaleva says she has paid up to $100,000 for Zverev’s works, but that such high quality pieces can be found only in Moscow and generally via private sales. She said she does not approach her collection as an investment, adding at one point in our interview that “I only buy what I like.” “I see the mission of our museum as promoting the non-conformists internationally, not on the market, but on the international cultural arena,” she said.

Lobachevskaya, with a background in film, has helped give the museum a modern, cinematic flair evident in its lighting, music, and multimedia displays, which create — rather than dictate — a unique atmosphere.

The success of GV Gold, which landed Opaleva on Forbes' list of Russia’s wealthiest women with an estimated fortune of $260 million (a sum she neither confirms nor denies) means she can now devote most of her time to her collection.

In 2018, she footed the nearly 700,000€ cost of the museum’s first foreign exhibition, “New Flight to Solaris,” a conceptualisation of late Soviet film director Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1972 science-fiction movie “Solaris” through nonconformist art at the Franco Zeffirelli foundation in Florence.

The full trilogy of exhibitions she has sponsored based on Tarkovsky’s films — the others are “Stalker” and “Andrei Rublev” — will be shown this summer in the State Tretyakov Gallery’s new section to inaugurate its expansion into the formerly adjacent Central House of Artists.

AZ Museum