Nadya Plungian: Curator Who Goes against the Grain

Elena Melnikova. Excursion to the Ball Bearing factory, 1937. Courtesy of The State Museum and Exhibition Center 'ROSIZO'

Moscow based art curator Nadezhda Plungian has a talent for creating new narratives around overlooked themes and this year she has two major institutional shows in the Russian capital which show that even large-scale state museums are finding a place for unconventional voices that shake up the status quo.

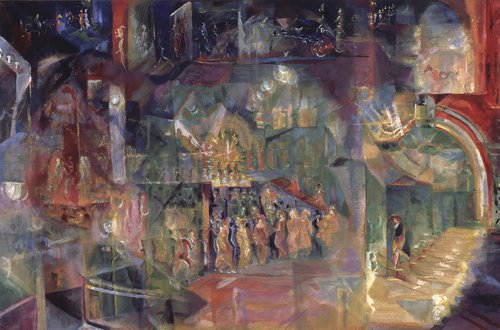

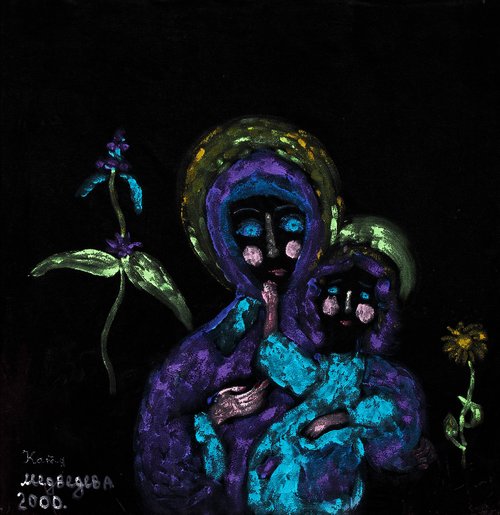

A summer exhibition at the Museum of Moscow, ‘Moskvichka. Women in the Soviet Capital in the 1920s and 1930s’ has been curated by Nadya Plungian together with Ksenia Guseva and it comes off the back of another big show in Moscow, this time at the Museum of Russian Impressionism, also curated by Plungian about the long since forgotten association of Soviet Avant Garde artists called ‘Group 13. In the Alleys of Times’. Both of these exhibitions look at Soviet city life in the first decades of the USSR and include the work of artists such as Nadezhda Kashina (1896–1977), Tatiana Mavrina (1902–1990), Vladimir Milashevsky (1893–1976), Antonina Sofronova (1892–1966) and Boris Rybchenkov (1899–1966). There are parallels between Plungian's recent book ‘The Birth of a Soviet Woman’ published by the Garage Museum for Contemporary Art in 2022 and the theme of the ‘Moskvichka’ exhibition.

As a curator and art historian, on the surface Plungian appears to relish narratives that flow and evolve between one another, something with which she disagrees. "I was working on the projects for Museum of Russian Impressionism and the Museum of Moscow at the same time, but I cannot say I saw them as connected. However, if this is how they are perceived, why not? [Art critic] Anna Tolstova saw ‘In the Alleys of Times’ as a feminist exhibition because it analyses phenomena that have been sidelined by culture. Such a reading is possible, as is any other interpretation. The project has a life of its own. I am interested in the history of Soviet modernism in the first half of the twentieth century, I like systematising and revising it in a variety of different contexts. I love Group 13 and always refer to them in my articles or books because I think they are a major phenomenon in Soviet art, certainly [on a par with] with Vladimir Lebedev's ‘Detgiz’ or Vladimir Favorsky’s school. And I found it exciting to take Boris Rybchenkov's landscapes out from the Museum of Moscow, where they are rarely exhibited, or to request Roman Semashkevich's ‘Tea Room’ from the Russian Museum. I want these artists to become recognized and loved by many," she says.

Plungian readily admits the connection between her book ‘The Birth of a Soviet Woman’ and the exhibition at the Museum of Moscow. "I was inspired by the book when I was working on the exhibition. The sections I prepared for the exhibition partly follow the structure proposed in my book, although I try not to repeat myself”. In the end, the sequence does not relate very closely to the book and the central theme is different as the Moscow images had to be analysed and placed in a dialogue with Ksenia Guseva’s themes.

As the exhibition project evolved, ‘Moskvichka’ became a scientific and artistic ‘testing ground’, where many years of research by different writers and experts came together. For Guseva, it is about the history of fashion and textiles, the synthesis of art and industry, a whole series of beautiful exhibitions on this topic. For Rustam Gabbasov, the designer of the exhibition, it is an in-depth engagement with Soviet fonts from different decades. Anna Rumyantseva, the architect of the exhibition, has created a very interesting wooden structure, subtly interpreting the architecture, arts and crafts, and colour of the 1920s and 1930s. And there is the work of Maria Orlova and Andrei Skatkov, costume and fashion historians.

Plungian's curatorial profile has evolved over the past decade. She loves to work in a team and create historical exhibitions in which her mission is to correct popular opinions about individual artists as well as entire trends in Russian art.

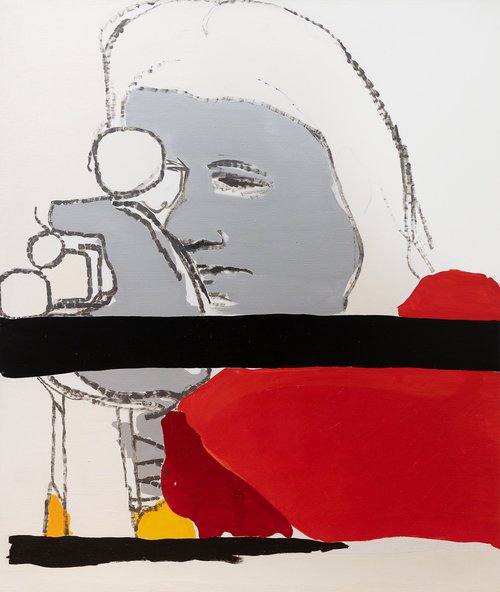

Her two-part project ‘Modernism Without a Manifesto’, shown at the Moscow Museum of Modern Art in 2017–2018, consisted of works owned by Russian collector Roman Babichev. A curatorial team was assembled that included Alexandra Selivanova, Valentin Diaconov, Maria Silina, and Olga Davydova, in addition to Plungian, who was responsible for the art of the 1940s and 1950s. Contrary to what most art historians believe, she considers this period to be a critical motor in the national artistic processes. She and her colleagues on the project wanted to show the division between the avant-garde and socialist realism, for so long a major defining factor in Russian art history, has actually been harmful and has not clarified anything.

More recently, Plungian has been working at the Municipal Gallery on Shabolovka in Moscow. There, she and curator Alexandra Selivanova, who heads up the venue, have curated numerous memorable projects including the outstanding ‘Surrealism in the Land of Bolsheviks’ in 2017. Together, Plungian and Selivanova demonstrated that an artistic movement, which Soviet and post-Soviet versions of history asserted did not exist in Russia, had in fact been born and lived in the USSR under the most difficult of circumstances. Writer, artist and bohemian Yuri Yurkun (1895–1938) was one of the heros of this show as well as the current exhibition ‘In the Alleys of Times’.

In the exhibition ‘Soviet Antiquity’ which they curated a year later, Plungian and Selivanova showed how the genealogy of images of early Soviet art, not just monumental art, could be traced back to Greek and Roman subjects. Plungian has taken a similar approach to Group 13 her roster comprising Vladimir Milashevsky, Daniil Daran (1894–1964), Nikolai Kuzmin (1890–1987), Tatiana Mavrina, Nadezhda Kashina, Antonina Sofronova, Valentin Yustitsky (1894–1951), Olga Gildebrandt-Arbenina (1897–1980) among others at the Museum of Russian Impressionism exhibition. She encourages us to see their art as urban Soviet Art Deco, to appreciate its individualism, its focus on fashion, on technical innovations and leisure time.

Previously marginalised as third-rate artists, Plungian firmly believes that this group explains life in the Soviet Union from the 1920s to the 1950s better than other more famous artists have done before. She notes pointedly that Group 13 flourished both during and after the Second World War. She also argues that it is time to re-evaluate artists like Tatiana Mavrina, insisting that art critics should not be looking at Mavrina solely through the prism of her late style, which is close to lubok, traditional Russian coloured folk prints. Instead, they should be looking with fresh eyes at her early, experimental works.

Plungian the curator juxtaposes the works of members of Group 13 with works by French artists on loan from the State Pushkin Museum. Doing so, she argues that they are not only comparable but sometimes even superior to their European counterparts. She believes the story that began at the Museum of Russian Impressionism exhibition remains far from finished. What she now envisages is mounting a retrospective dedicated to the work of Group 13 leader, Vladimir Milashevsky.

As for the ‘Moskvichka’ exhibition, Plungian and Guseva did not simply create a gallery of female images and specific historical figures. They displayed an era, that was sandwiched between the Civil War in Russia (1918–1922) and the Second World War, in all its complexity, and not just in black and white. That said, despite the title and theme, and keeping in mind that Plungian began working as a curator of feminist festivals and exhibitions in the first half of the 2010s, this project, with its detailed study of women depicted in and creating art, takes the keen visitor back to universal questions about all inhabitants of the country at the time.

‘Moskvichka’ opens with a painting by Mikhail Tsybasov (1904–1967) ‘Asya’, created in 1932–33, who Plungian describes as "an exemplary urban woman from the 1930s ... her sad gaze seems to have drowned in retouching, like a newspaper photograph" and it ends with a 1945 painting ‘In the Subway’ by Samuil Adlivankin (1897–1966), which depicts a man in an underground train lost in thought, dressed in a cloak and hat, who seems to be simultaneously passing by and disappearing. It is a fitting finale which conveys a sense of the fragility of human memory that runs through this exhibition.

Moskvichka. Women in the Soviet capital in the 1920-1930s

Moscow, Russia

April 24 – August 25, 2024

Group 13. Through the Alleys of Times

Museum of Russian Impressionism

Moscow, Russia

February 8 – June 2