Marina Koldobskaya’s Painterly Thought-Processes

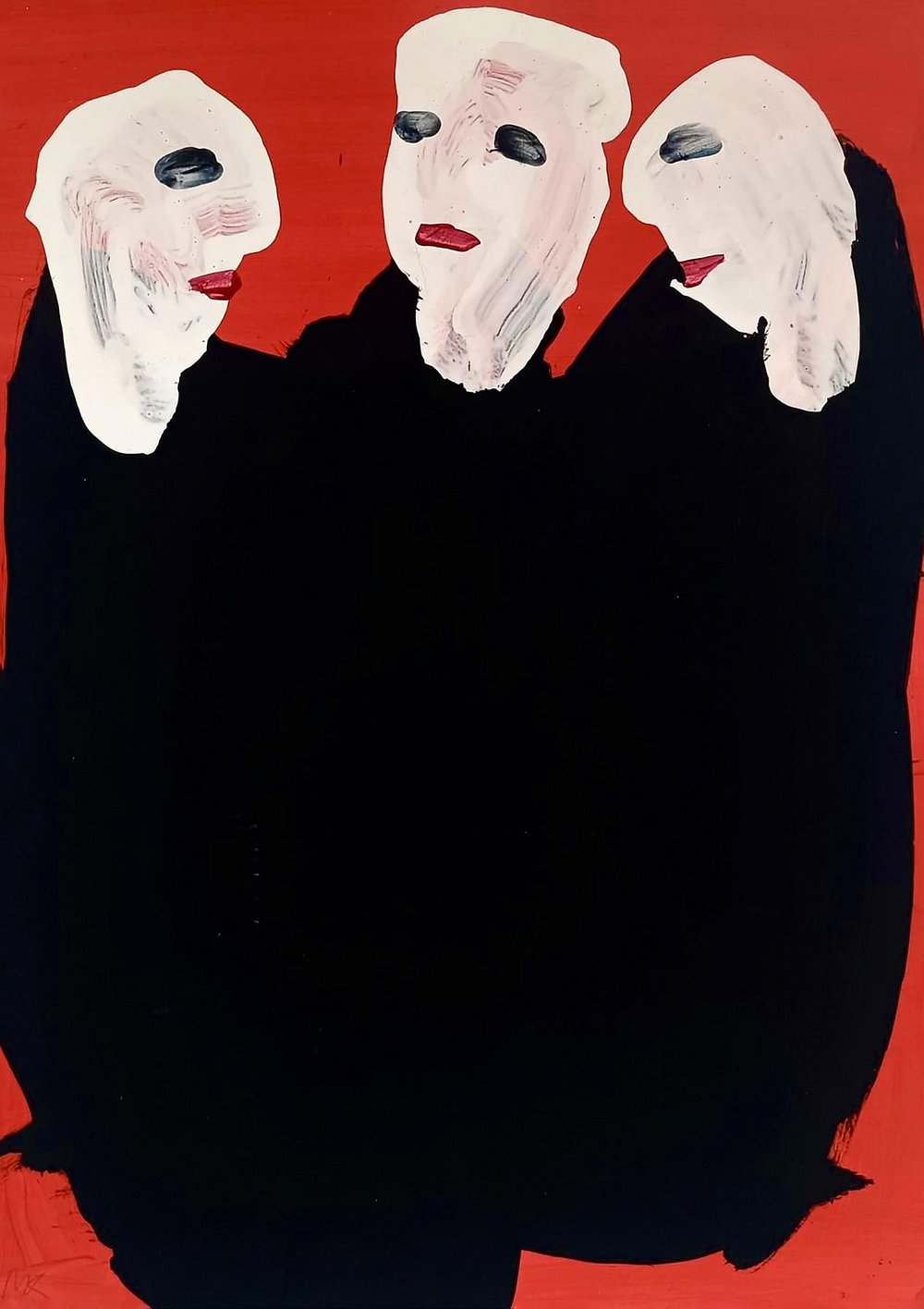

Marina Koldobskaya. Trinity. Courtesy of the artist

Based today in Berlin, this Leningrad-born artist has a solo exhibition in the seaside town of Budva, Montenegro. Koldobskaya, known for minimalist expressionism, invites viewers to explore profound themes of human ethics and faith through her iconic imagery.

‘Red Corner’ is Marina Koldobskaya (b.1961) ’s most recent exhibition, a painter originally from Russia whose minimalist expressionism has become her trademark. A meditation on icons reduced to a bare minimum of painterly gestures to be immediately recognisable, the viewer is surrounded by familiar images of human morality, ethics, meaning and faith: the Virgin Mary, the Holy Trinity, Christ and Archangels portrayed in a stark form, stripped of detail, both haunting and menacing; these bearers of western moral values which have upheld and guided society. Why has she turned to such images? “During tough times, we talk about what matters most in life. I think we are on the eve of a Third World War, we are talking about life, death and the end of everything. What other ways do we have to discuss these things?”

Speaking to and through art, Koldobskaya is engaging with layers of Russian and Byzantine visual tradition from fourteenth century icons through to soviet pop art of the 1960s via Suprematism, which itself is rooted in icons. The exhibition is the result of the artist’s month-long stay in the newly-founded NovaRiznica Balkan residency, initiated in Montenegro by art dealer and cultural entrepreneur Marat Guelman (declared a foreign agent by the Russian authorities) for Russian artists in exile.

“I was happy, I was given as much paint, canvas and paper as I wanted and I painted and painted.” About her process, she paraphrases Cezanne’s “thinking with paintbrush in hand” it has become her personal, non-verbal way of understanding the world. With little control over her process, she never knows which painting will turn out well, usually ending up with piles of paper and canvases. But she’s evolving, she admits, “Now I throw away only about half, ten years ago 90% would end up in the bin.”

She poses questions, provokes and contextualises our contemporary life and its constituents through her visual phrasebook. Koldobskaya’s images are reduced to the minimum necessary for interpretation, succinct yet powerful symbols like designs for logos. You should be able to scale up or down any image, this is an important criterion for her, that an image can still be read either as a tiny badge or covering the wall of a house. It is something of the approach of a designer. And yet these works are hand-painted, emanating gestural energy, wet paint dripping down the canvas. In this respect she sees a kinship with calligraphy, the intersection of expression and discipline.

This exhibition is executed in her trademark colours of red, white and black - the colours of constructivism and agitprop Soviet propaganda - but also the base colours of archaic human expression: white clay, red ochre and black soot. Enough to talk about all the main things in life: darkness and light; fire and blood; earth and sky. The colours do not come straight out of the tube, she carefully mixes them. “Simple doesn’t mean easy, this is painting”, she puts it. Even the black is deceptive because it has tiny additions of blue and red to make it more complex and painterly, but this is no special secret, she learnt this trick as a young art student.

Koldobskaya studied design at St. Petersburg’s renowned Stieglitz Art Academy (then known as the Mukhina school), but her real coming of age happened when she found the Society for Experimental Visual Art (TEII), where she discovered the existence of non-conformist unofficial art “for me it was like discovering Atlantis”, she recalls. She quickly joined the Society, and with this collective took over Pushkinskaya 10, a legendary artist squat in the heart of St. Petersburg.

“And then began chaos, or freedom.” Koldobskaya stayed in the art centre for over two decades, becoming a formative part of this unique creative cluster.

Koldobskaya evidently channels many artistic influences, to name a few Russian predecessors: Mikhail Larionov (1881–1964), Vladimir Yakovlev (1934–1998) and Mikhail Roginsky (1931–2004); contemporaries among the St. Petersburg New Artists and Mitki groups such as Olga (b. 1960) and Alexander Florensky (b. 1960), Ivan Sotnikov (1961-2015), neo-primitivists such as Irina Zatulovskaya (b. 1954) and younger generations evidently bear her imprint, namely Alisa Yoffe (b. 1987). Ukrainian naive artists Maria Prymachenko (1909–1997) and Polina Raiko (1928–2004) (Koldobskaya is part Ukrainian herself), as well as broader folk and naive art. This collective patchwork of influences form the fabric of her output and yet she is unmistakeably unique and recognisable.

Apart from her prolific artistic output, Koldobskaya has also curated numerous exhibitions, worked as an art journalist, served as director of two institutions, The Museum of Non-Conformist art and the St. Petersburg branch of the country’s first contemporary art institution, the National Centre for Contemporary Art (NCCA). She co-founded CYLAND media art laboratory and organised the media art festival Cyfest together with Anna Frants (b. 1965). Koldobskaya is also a poet, illustrating print runs of her own poetry books. She organised the country’s first female art groups and exhibitions, yet she doesn’t call herself a feminist. So many and ever-changing are her faces, that sometimes it is hard to keep up but critic Mikhail Sidlin explains: “She was borne by the wind of freedom of the late eighties, and her metamorphoses are a life project.”

Is she still changing today? Over the past two years, since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Koldobskaya has been living and working in Berlin. Has this move changed her, has it affected her art? “Life has changed, but I don’t think any differently. Certain elements in my art are becoming more defined. I think there is some kind of concentration going on and some peripheral elements are being eliminated”, she reflects.

Koldobskaya co-curated ‘Heartbeat’ a new collective exhibition of six female artists in Berlin last summer, which included two artists from Russia, two from Ukraine, and two from Belarus. A rare example of collaboration between cultural representatives of these nations. The process of curation was entirely collective and thoroughly democratic. Koldobskaya loathes cancel culture. Her contribution was a huge wall mural of seven menacing cat-like creatures, black paint smeared and dripping in a unified mass and seven pairs of evil eyes staring from the wall.

“Those who were heroes have become criminals. And vice versa. Those we consider criminals are being hailed as heroes. This is all an inversion of black and white. There are huge holes in all this cultural fabric, and through them hell is seeping out.” Not many artists have managed to continue their practice, find a visual language fitting to the current cataclysmic state of European existence, but Marina Koldobskaya with her raw sincerity and presence is one whose visual expression lends itself to current affairs, speaking not only for herself, but for many of us who feel voiceless and lost.

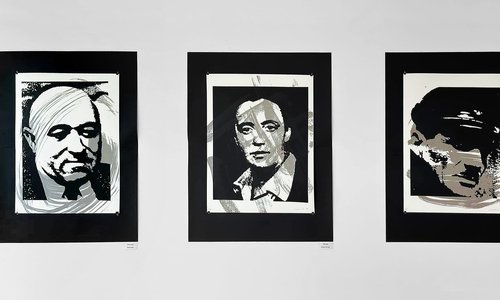

Marina Koldobskaya. Red Corner

Montenegro European Art Community

Budva, Montenegro

23 May – 9 June, 2024