Marina Alexeeva’s Thoughts In and Out of the Box

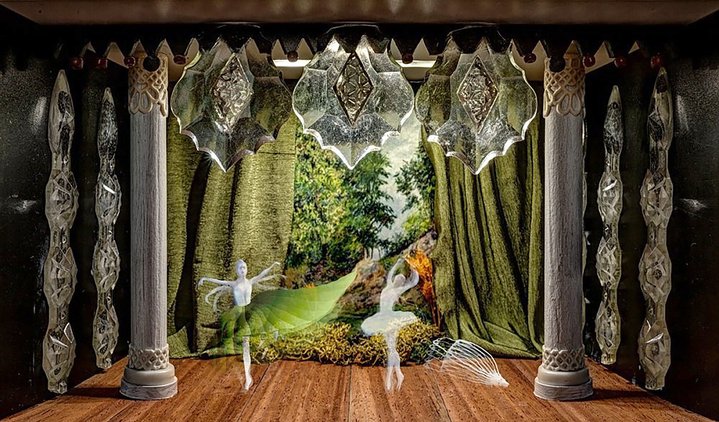

Marina Alexeeva. Office, 2019. Mixed-media, video, sound installation. 38x38x38 cm. Courtesy of Shtager&Shch Gallery

St. Petersburg artist Marina Alexeeva is opening a solo show at Shtager&Shch Gallery in London. Her signature brew of small-scale video art and her laconic drawings both reflect the tragic absurdity of the world around us.

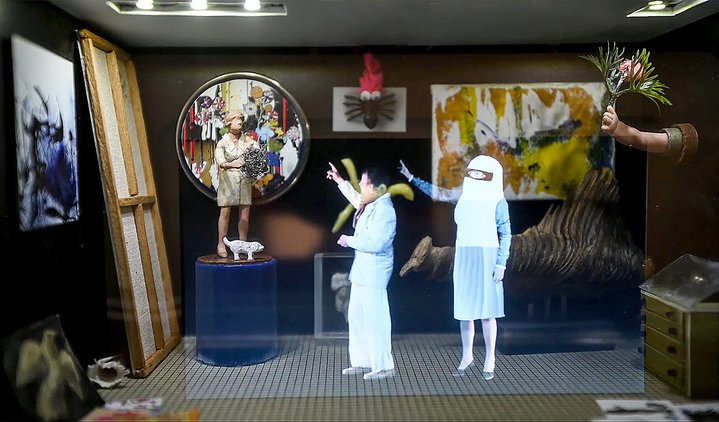

Although Marina Alexeeva (b.1959)’s art can be scaled up to monumental proportions, occupying a whole theatre stage or the facade of an apartment building, such as in her project ‘Prose and Workers’ Settlement’, which she co-authored with composer Vladimir Rannev, she feels most comfortable working in an idiosyncratic hybrid medium that demands intimacy with the spectator. The only way to experience her signature ‘life-boxes’ is one-on-one interaction, a voyeuristic pleasure. Her life-boxes are little black boxes with a small window or a peephole in the front wall. Inside, magic happens. In a tiny 3D model of an interior, hand-drawn cartoon people and creatures live mysterious lives full of catastrophes and sudden metamorphoses.

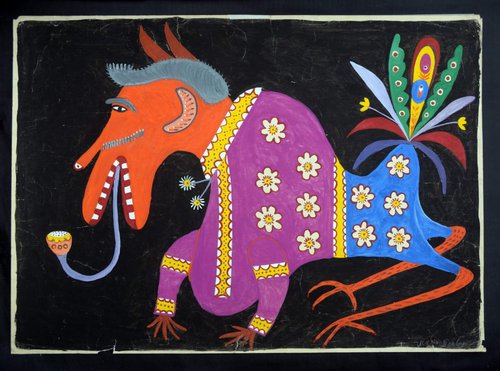

Alexeeva was trained as a ceramic artist in her hometown of Leningrad (now St. Petersburg) at the Mukhina Higher School for Art and Industry, now the Stieglitz Academy. She is a well-known figure on the city’s art scene and used to host art exhibitions in her studio, also her home, on the outskirts of the city. She called it the Selskaya Zhizn (Rural Life) gallery. It took her many years to develop her signature art medium; she set out at first creating ‘secrets’, glass-covered assemblages reminiscent of a Russian children’s game where buttons, stones and other little treasures are hidden in holes in the ground and covered by shards of bottle glass. Next came miniature models of interiors built inside boxes with a glass front wall. Alexeeva assembled them from found objects and household rubbish, creating the illusion of a lived-in, inhabited space, such as a flat or a train compartment. The turning point came when she met engineer Sergey Karlov who explained to her how to project videos inside the boxes, using a semi-transparent mirror. This way, hand-drawn cartoon figures appeared on the background of a miniature interior. Alexeeva, who learned animation techniques from her husband Boris Kazakov, a well-known animation cartoon artist, loved the idea from the outset. Finally, it seemed, her empty little spaces filled up with life, a life so surreal it seems to have been invented in a dream. “When I start to work on a new piece, I never have a plot in mind”, she once told me. “The transformations show what’s in my character’s mind, a person might be a cute bunny on the outside and a crocodile inside.” She never knows where her creative process will lead her, a spider can turn into a teacup or the other way around. She never knows how long they will take, sometimes it will take her up to six months to finish a ‘life-box’.

Last year the surreal imagery of her animated cartoons suddenly started to look too realistic for some audiences and this led to her works being banned from public exhibitions. One state museum in Russia refused to show a life-box dedicated to the Russian-Ukrainian landscape painter Arkhip Kuindzhi (1841-1910), a native of Mariupol. “I always have a lot of action in my works, all sorts of explosions and guns, and nobody used to care. But now people ask to remove everything that reminds them of an explosion. They are afraid in advance,” she says. “Maybe it’s time to open underground galleries again”. She has even considered restarting her Rural Life gallery to give her fellow artists a space for free expression.

Transporting Alexeeva’s fragile works overseas is a logistical challenge in the time of closed borders and cancelled flights. However, art dealer Marina Shtager, another native of St.Petersburg who lives in the UK, has brought several of them to London in time for the opening of her new gallery space in Fitzrovia. In her new works, Alexeeva turns to institutional critique, rendered in her own whimsical, tongue-in-cheek way. The pomp and pathos of grand cultural institutions ooze away in a wink, and a ballet performance and a gallery visit turn into a grotesque dance macabre. The exhibition called ‘Habitats. Semiotics of Hope(less)’ includes five life-boxes and a new series of drawings. These graphic works were inspired by the tragic events of the last year, yet in an indirect way. Each one shows a single object and the word NO, a timely symbol of an era where destruction and negation reign both in the physical world and in the realm of ideas. “I have the impression that now there’s NO to everything.”, as Alexeeva puts it. “Everything loses its meaning. There will be no this and no that, etcetera, ad infinitum. Everything is slowly being scratched out”.