Lost in Translation, Badalov’s Language of Nomadism

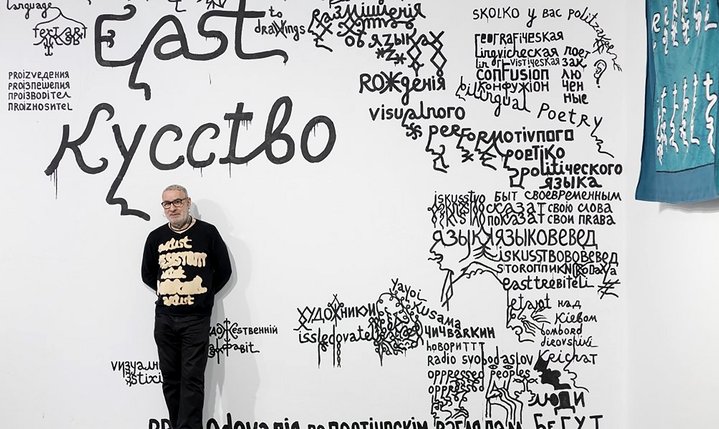

Babi Badalov. Almaty. 2023. Courtesy of Aspan Gallery

‘To see, to read, to tell’, the first solo exhibition in Kazakhstan of established Azerbaijani-born artist Babi Badalov has opened at the Aspan Gallery in Almaty.

Living as a refugee in France for the past 15 years, Babi Badalov is a true 21st century nomad. Born in a village in the south of Soviet Azerbaijan in 1959, he lived in Russia in the 1980s before moving to the USA after perestroika in the 1990s. He found himself returning home after some years and then he emigrated again, this time to Britain. If it is hard to keep up with his roving biography his origins as an artist are easier to define. It was in Leningrad in the 1980s that he first found his voice as an artist. He enrolled in the Academy of Arts, but it was the city’s vibrant underground art scene which really piqued his interest, where he met and became friends with artists such as Valentin Savchenko (b. 1955), Yuri Gurov (1953–1992), and Vadim Ovchinnikov (1951–1996) and Badalov became an active player himself on the scene, eventually identifying with the New Artists group. Later, in exile, he developed his mature, idiosyncratic style, which was formed gradually through his wanderings around the globe, the bitter-sweet experiences of an émigré.

These experiences are particularly relevant today. ‘To see, to read, to tell’ is a timely show presenting interconnected themes around globalization, national identity, emigration, and the problems of language. Such issues lie at the heart of Badalov’s work and are being discussed actively now in the Kazakhstani cultural milieu. Over the past year Kazakhstan, famous for its nomadism, has become a destination for new Russian emigrants.

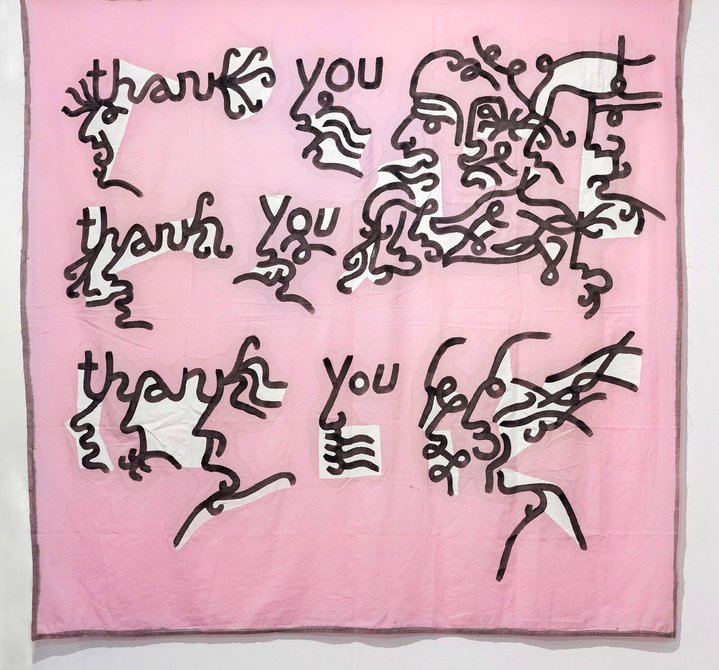

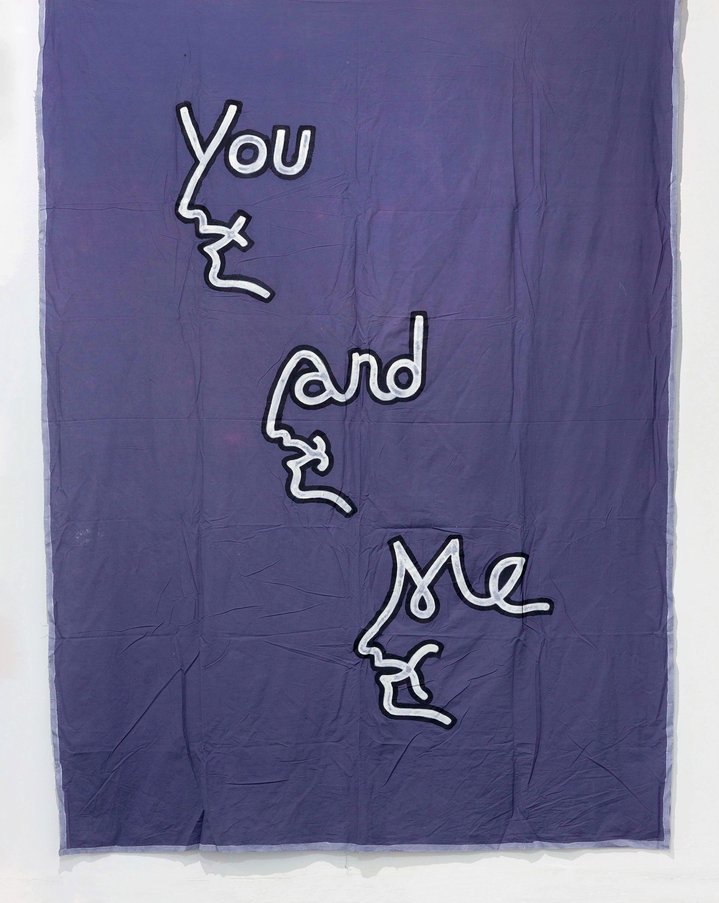

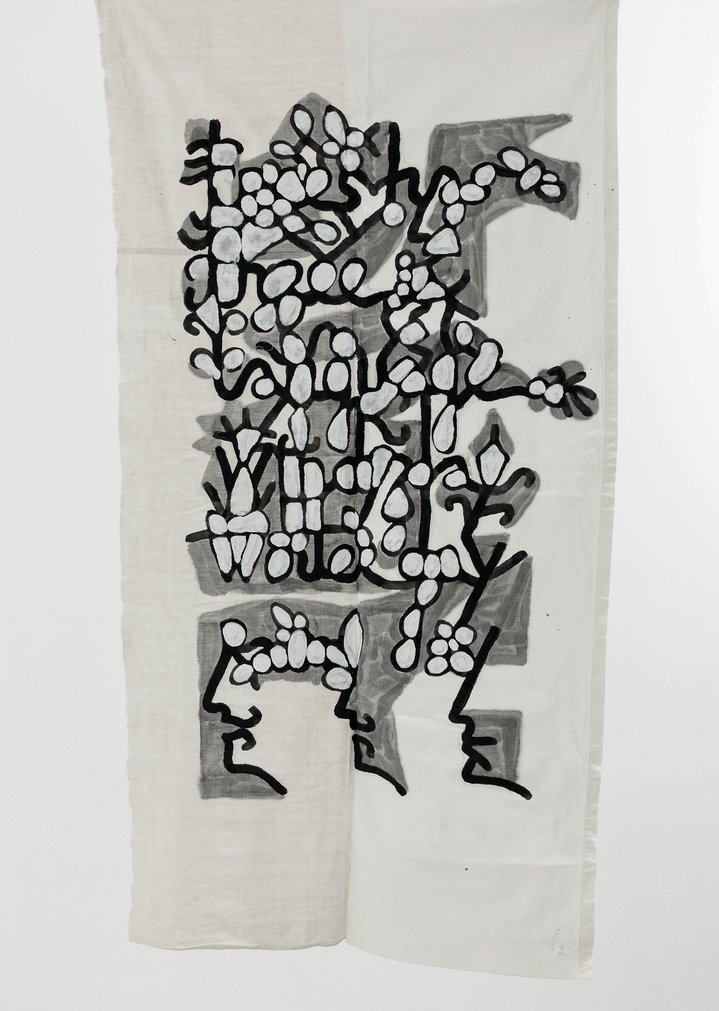

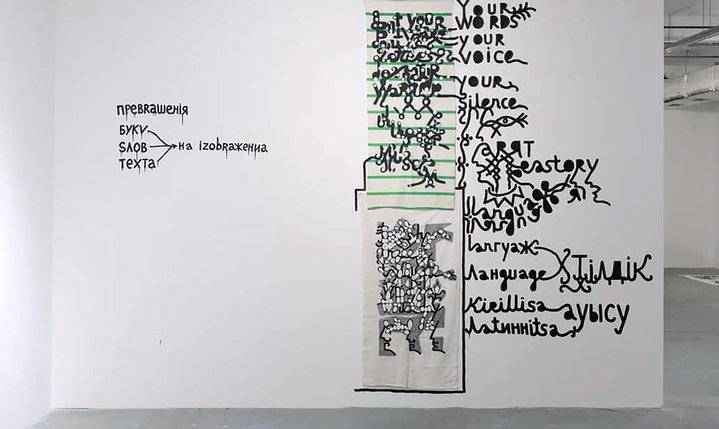

Babi Badalov’s work is often assembled into total installations. Here, strewn haphazardly all around the exhibition space there are canvasses stuck to the walls and hanging from ropes; there are sheets, curtains and even t-shirts, things he buys in second hand stores which have their own stories from the past. It is as if the artist brings them to life again through upcycling in his art practice, decorating them in his own inimitable style with cyrillic and latin inscriptions mixed together to form one word, while the font he uses for his artist's signature adds a dash of the orient. Word play transforms 'nationalism' into 'naSEEonalism' or 'naSEAonalism'. The text is woven with ornaments and drawings into a single image evocative of the layering of graffiti in an émigré neighbourhood. The limits of the canvas are ephemeral for nomadic artists and sometimes the words and lines from one work or the other spill out over directly onto the wall.

This exhibition in Kazakhstan is important for Badalov in terms of the local audience: "Here I see the possibilities of meaningful dialogue with my audience, because people here understand both English and Russian. I love the Russian language; it is very poetic. I can't write in English so organically, but here I can make a bilingual exhibition."

In the show, the Kazakh context is mixed with an international one, spiced with émigré colours lifted from the Parisian district of Barbes where the artist's studio is located. Sheets of canvas are ‘hanging out to dry’ on ropes; there are T-shirts hanging from poles, in a parody of a fake designer clothes street market, but instead of ‘Hucci’ and ‘Versase’ logos the garments are branded by acute social problems. One inscription ‘Uyghur lives matter’ reminds us that this region where the Chinese government has been carrying out genocide against Uyghurs since 2014 is only a few hundred kilometres from Almaty. A ‘SocialEast’ t-shirt hanging nearby summons the West to turn to the East and not ignore the tragedies taking place there. There is a sense here that a global world in which people care about one another regardless of nationality, language or social status is still a distant reality. The plight of the Uyghurs lies outside the Western political agenda, just as the daily challenges of the marginalised, refugees and immigrants never come to the attention of well-meaning citizens. The artist has also dedicated a monumental mural on the gallery wall to the persecution of the Uyghurs in China.

Badalov's art in some ways evokes the lyricism of a personal diary. The best way of describing one’s life, he said during an artist talk organised by the gallery, is in book form, although he added that few people actually write one. For him his work is a kind of autobiography of both his thoughts and experiences. As a nomad himself, his vision is defined by the nomadic gaze, which is in turn a defining quality of the art he produces.

The West, the East, the Russian-speaking post-soviet space; words, graphic design and ornament all of these elements are mixed together in his art and sometimes hard to read one overriding message. As a viewer you have the sense that you find yourself in an immigrant quarter and your ears (and eyes) are bombarded with multilingual chatter. You try to hear just one sentence, you can't make it out, and you wonder if there is any real comprehension possible at all. Looking at his work from this perspective, as if from the alienation of an immigrant, hostage to a lack of knowledge of the language and culture, the emptiness or vagueness between the words and the patterns takes on a special meaning. Or maybe it is that the viewer is in a laboratory of dreams constructing a synthetic world culture. One where no language or nation is lost entirely, but they all contribute to a global melting pot. Maybe there is a model for a future global world where people and cultures maintain their uniqueness, but at the same time are not alienated from one another?

Loss of self and identity is one common problem experienced by people who emigrate. Far away from their ‘own’ place, many have to find new answers to the question ‘Who am I?’ One of the basic answers - that of being a nomad - can be seen as a new starting point from which it is then possible to build up new, complex structures in one’s life. Nomads jumpacross borders and think on a supra-national level, embracing the planet and humanity as a whole. Nomads absorb different cultures, open themselves to others, try to find a common language. They feel fragmentation and boundaries but then through processing the experience of travelling, they become moulded by this, it makes them free and receptive. In the end, the diary gathered from all of Babi Badalov's paintings manifests itself in the figure of artist-nomad who writes a book in all languages at the same time, yet mysteriously also in only one: his own.