Liza Bobkova’s Porcelain Pack of Cards

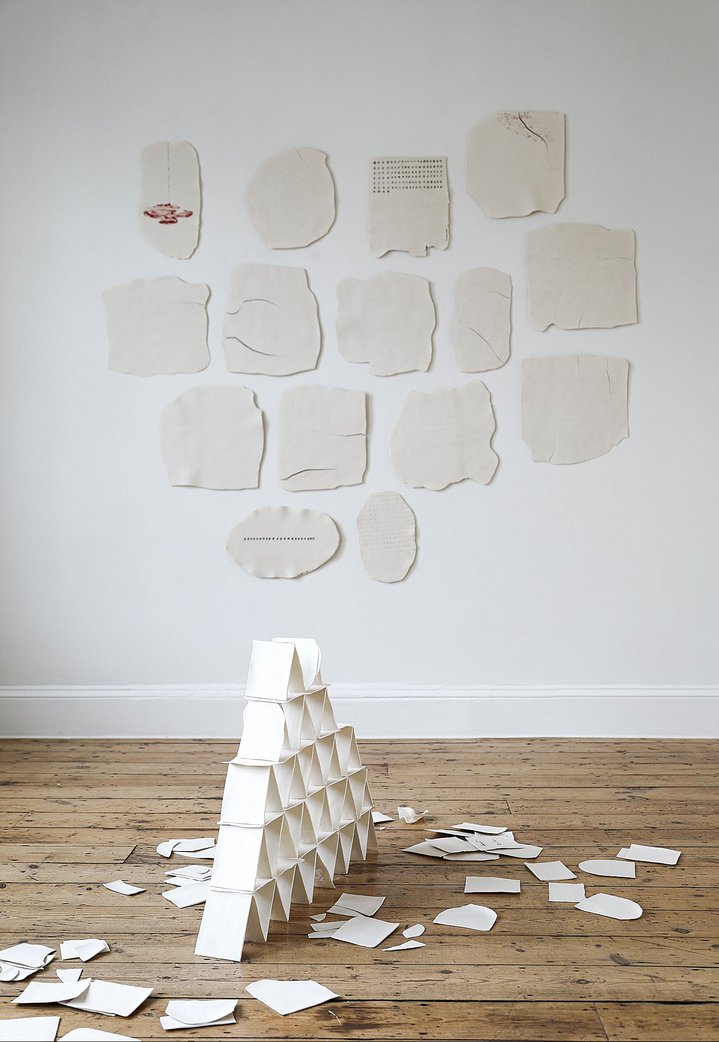

Liza Bobkova: Restoration of Time. Exhibition view. London, 2024. Courtesy of Art 4 Gallery

Liza Bobkova’s current exhibition at Art 4, Cromwell Place in London is a realm of Alice in Wonderland absurdity where delicate porcelain towers of cards evoke childhood wonder and the fragility of creation. Amidst the art’s allure, visitors confront a transient dance between stability and collapse.

Porcelain was known as white gold. It took a thousand years before anyone outside China was able to find the formula: Johann Böttger, a German alchemist, stumbled on the hard paste in 1708 in pursuit of making gold. The opening of Liza Bobkova’s (b. 1987) exhibition at Art 4 in London’s Cromwell Place was jam-packed and the artist was anxious about the fragile focal point of the show: she had re-created a tower of cards, like the ones she made in her childhood. She placed two cards at an angle to each other and once they balanced, she packed four other cards around as a wigwam. Then she built on top of that and tried to make her tower of Babel as high as possible until it tumbled. Today, her cards on the floor of Cromwell Place are not made of paper or plastic but porcelain. The structure was simpler, paired down to triangle upon triangle: it is seven floors high with a base of seven card houses, almost an equilateral triangle.

There was a thirty-metre queue of people in the street waiting to get in. Once through Security and with drinks in hand they climbed the sturdy stairs and entered the enclosed space of the Wing Gallery, they were able to share in the thrill and danger Liza Bobkova had experienced as a child when building her house of cards. Like a tree in autumn, this Pagoda of cards had a canopy of porcelain cards around it. An interactive work of art, it is up to each individual visitor to decide whether these are building blocks, waiting to be added on top of the ever-expanding edifice, or whether they are the first signs of the whole caboodle imploding.

At the end of the opening night, Bobkova was so relieved that no-one had trod on her creation or damaged it that she jumped with joy. The House of Cards shook. She nearly destroyed her own fragile castle. Sitting in the gallery two days later she told me that ‘In my childhood I had a dream that a woman put her hand on a book, and she immediately understood everything in every book she touched.’ After going to the Art Academy in St Petersburg she spent some six years setting up a department of contemporary books in the library, so she acted on the dream, wanting to give students access to knowledge that had not been available before. Her dream has its own magic ambiguity, echoing Theodor Adorno’s declaration that ‘books say something without being read.’

Her mother decided Liza Bobkova had to be an artist. Maternal pride set her on path that was later made even clearer by an Ilya Kabakov (1933–2023) diptych word piece. The question is asked: ‘Volodya, where are you?’ Immediately, the comforting answer comes back: ‘I am here.’

Bobkova enjoyed her education and working at the Academy for six years, but she has stated, that ‘I am glad that I did not stop at the direction that the academy gave me. Artists with a classical education often stop at the edge of Method…’ She now adds ‘after making ideal things for years I wanted to make something wrong.’ The now long tradition of double thinking in Russia has helped her rebel against the outdated strict line of Greek thinking, which has become a straitjacket rather than a functional philosophy.

Bobkova was brought up in the Eastern part of the Russian Empire, near Vladivostok, so building Pagoda-like card houses made in an ancient Chinese material, conjures up the looming influence in the East of China. As the game with cards taught her, the biggest structures can collapse just as quickly and more spectacularly than small ones.

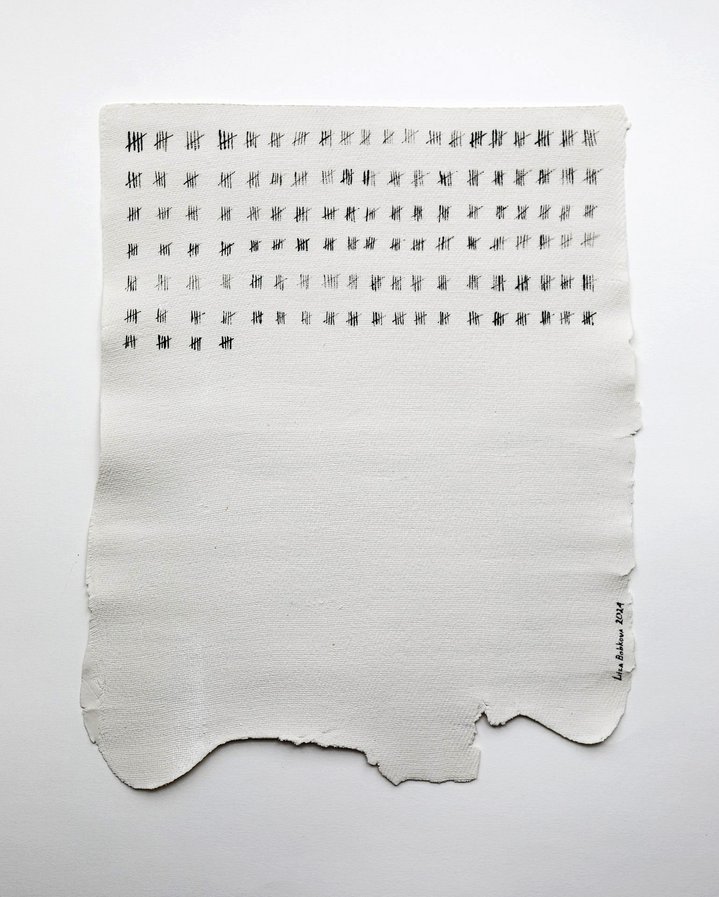

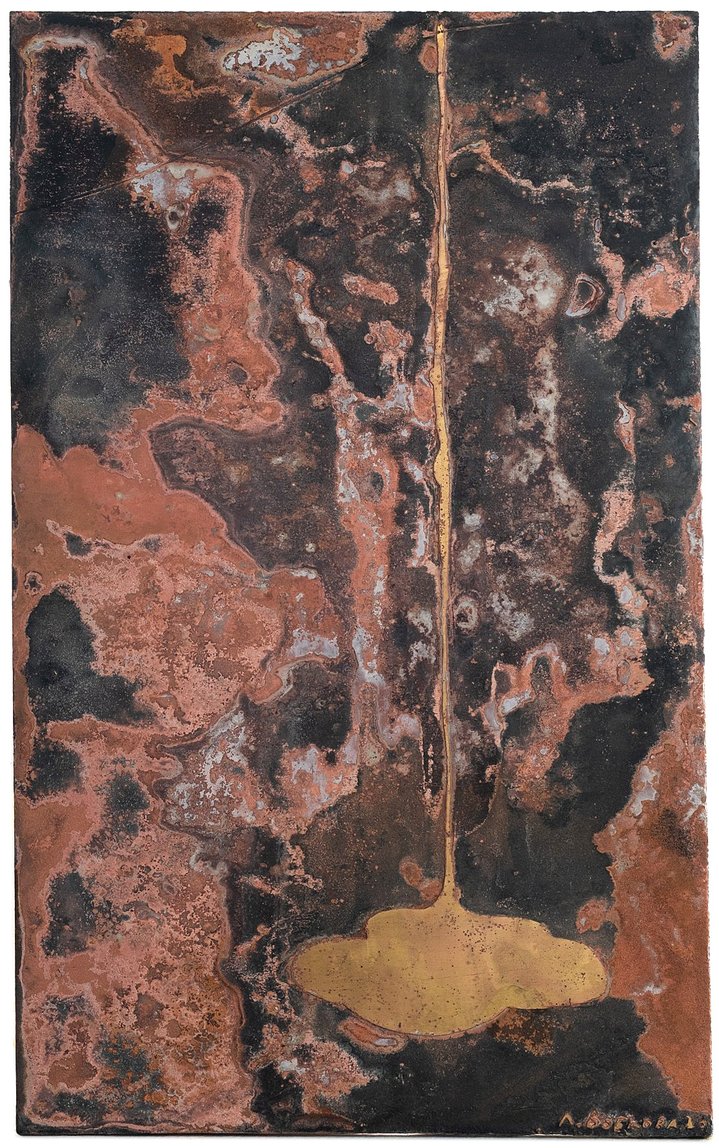

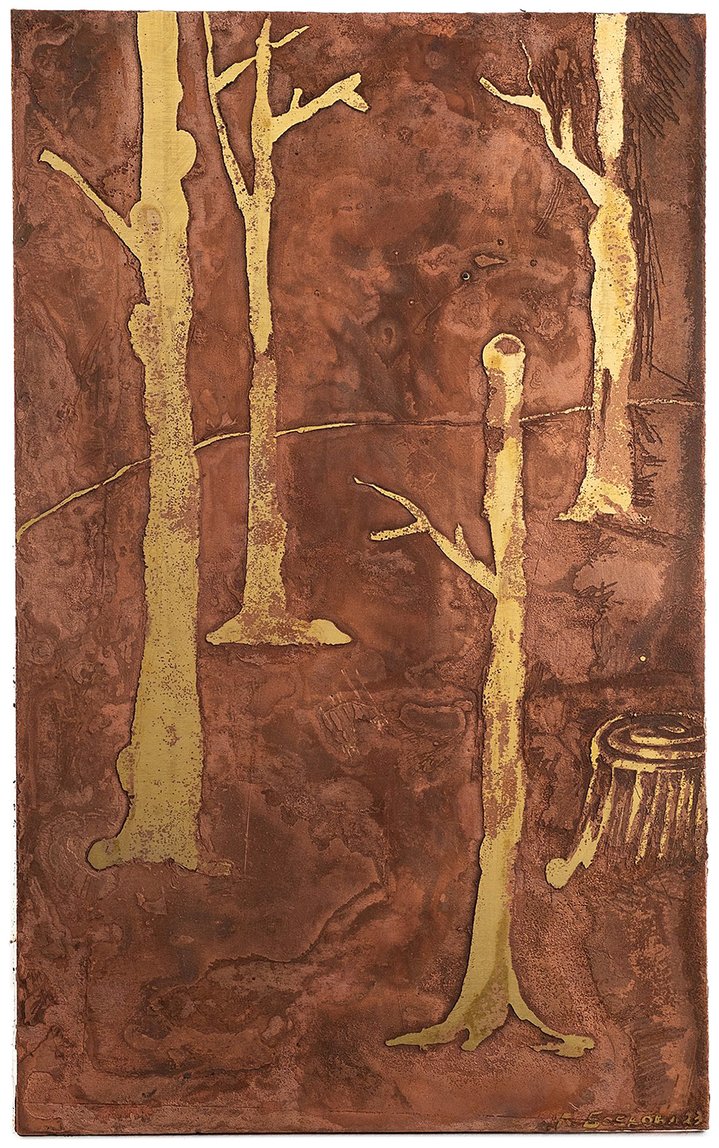

In the exhibition there are just as many works made in metal as porcelain ones, but the theme of the show, fragility in the face of time, is told most poetically in the brittle white gold paste. She is a Modernist, or at least a follower of Baudelaire, so likes the faults in the material. As Baudelaire promoted, she pushes harmony a certain distance but finds more meaning in the cracks and blemishes. She has made some works where she is fooling time as she has made calendars, where she has scratched days and weeks off, rather like a prisoner in a cell, but of course she must have done it when the material had still not fully hardened.

The artist interacts with the space with interconnecting metal spheres. These will remind Muscovites of an earlier installation she made at Galerie Iragui, which consisted of similar metal geometrical forms coming out of bright pink sand. Pink can be an ideal feminine colour. It has provided symbols for gay liberation. But thinking back to that Moscow installation while looking at the new show in London, I am overwhelmed with visions of the most sophisticated porcelain of all time: pink Sevres. Marie Antoinette considered it the height of luxury and owned the factory. A single cup in her day cost more than she paid even the foreman of the workers. Fortunately, the sands of time, whether pink or not, bring change.