Litichevsky and His Opus Comicum

Georgy Litichevsky. Intelligence of Flowers. Exhibition view. Courtesy of Iragui Gallery

Produced over the period of four decades, Georgy Litichevsky’s idiosyncratic graphic novels blend intellectual history with countercultural aesthetics, creating thought-provoking, alternative Russian narratives through vibrant visual storytelling.

Artist Georgy Litichevsky (b. 1956) boldly presents an alternative version of Russian history in his scroll work ‘Opus Comicum’. For the artist, alternative histories have become an endless saga as he constantly invents new and remarkable visual stories. Born in Dnepropetrovsk (now Dnipro, Ukraine), the artist built up his career in Russia and today lives in Nurnberg and has been creating his sharp witted pictorial stories over the past four decades. In Spring this year, the Vinzavod Centre for Contemporary Art in Moscow staged ‘Borders of Visibility’ an exhibition featuring a comic book by Litichevsky called ‘Ole vota.’ Translated from the Finno-Ugric language of the Komi-Zyrians from the Komi Republic in Northern Russia, the phrase means ‘I live, I see’. It connects the theme of a non-classical worldview with the phrase “I live, I see” by poet Vsevolod Nekrasov (1934-2009), perhaps best known today because of Erik Bulatov's (b. 1933) famous painting in which these words define the whole space. Written in Finno-Ugric, the phrase also echoes the biography of the great avant-gardist Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944), whose ancestors were princes of the Finno-Ugric Mansi people. In this comic piece, Litichevsky vividly and masterfully shows us, in the form of intertwining dreamlike visions, how the wild nature of the Urals (Yugra) influenced Kandinsky's spiritually inspired abstraction.

Georgy Litichevsky is not aligned with any artistic group or style, most often he is associated with Russian new wave art. This movement emerged in the late Soviet era as an alternative to abstruse and elitist conceptualism, the mainstream of unofficial art in the USSR. A graduate of the History Faculty of Lomonosov Moscow State University, specialising in ancient world history, Litichevsky in 1986 fell into the ‘bad’ company of the Kindergarten artist group. Its members, German Vinogradov (1957-2022), Andrey Roiter (b. 1960), Nikolay Filatov (b. 1951), and Gosha Ostretsov (b. 1968) were creating intentional bad art: art addressed to mass expectations. The art of the ‘kindergarteners’ can be compared with the work of Leningrad's ‘New Artists,’ led by Timur Novikov (1958-2002) and Viktor Tsoi (1962-1990). Their language is naive, absurd, brightly coloured, aggressive and devoid of the abstruseness and primness of conceptualists.

The comic style was finely tuned to late Soviet new wave aesthetics and ideologies. When we recently met at his home in Nurnberg, Georgy Litichevsky reflected how it all came about: “I was not crazy about comic books when I started to draw them. But as a child I watched cartoons, and flicked through magazines like ‘Murzilka’ (about a Soviet child correspondent – either a cat or a bear cub), and was fascinated by the graphics of unofficial circle artists in the magazine ‘Nauka i zhizn’ (Ed. ‘Science and Life.’) Before I had even heard of the word ‘comic’, I always drew stories with pictures. Then later, at university, I came across underground publications like the French Hara-Kiri, the predecessor of the scandalously famous political comic magazine Charlie Hebdo. I discovered that comics could be free, angry, and witty. I'm interested in combining intellectuality with brutality and the very comic structure of depicting narrative, where text moves as if in a film strip, and words are contained in ‘bubbles’ – phylacteries. And I still find this approach inspiring today after all those years. For me, this is an antidote to the conventional plots and clichés that dominate the institutional art environment.”

Importantly, Litichevsky emphasises the idea of mixing intellectual history with brutality, black humour, and the aesthetics of youth subculture. With courage he steps out of the familiar field of play with its fixed parameters and rules. In 1993, Litichevsky became a member of the editorial board of the legendary ‘The Art Magazine,’ published by Litichevsky's long-time friend Viktor Misiano who he met at university. Today, Litichevsky jokes he could enter the Guinness Book of Records for having published his comics in every single issue of ‘The Art Magazine’ from 1993 till today. For the anniversary 50th issue of ‘The Art Magazine’ on the theme of Education, Litichevsky drew a comic in which he identified the wedge between classical art education and contemporary art institutions which existed in the early 2000s. A young female curator, resembling Medusa Gorgon, cries out: “The Academy of Arts? Not worth the mental effort!” And she opens a contemporary art magazine: “I know and can do everything already because I regularly read The Art Magazine.”

In the role of trickster, Georgy Litichevsky moves away from the aesthetics of traditional comic books. Recently, he talked about how he conceives his opuses in the genre of the graphic novel rather than manga or comics. Graphic novels have complex plot lines, original image and text content, and are seen as a full-fledged art form.

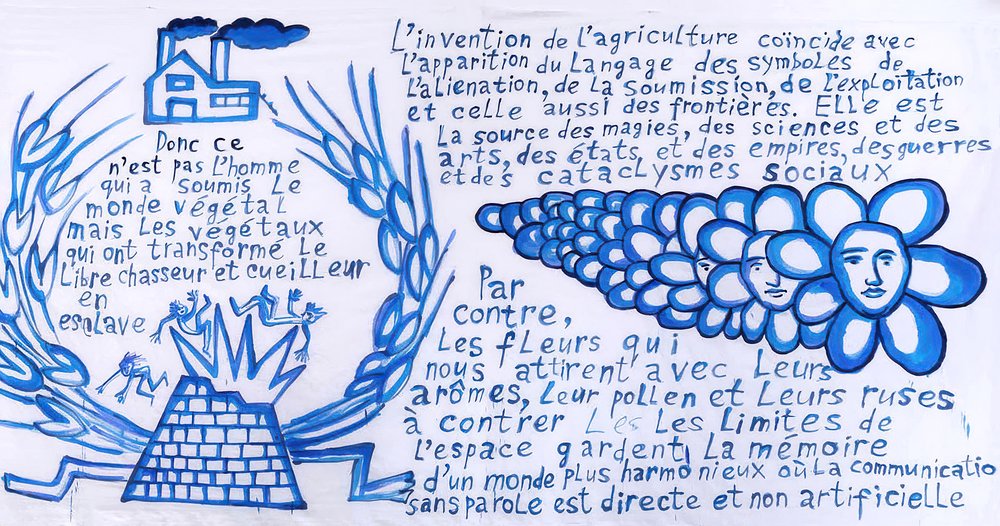

Ultimately, although it is his trademark medium, Litichevsky does not work exclusively in the genre of comic books. The Centre Pompidou in Paris owns a series of his large works on paper called ‘Flowers against the Fire Demon’, created in 2010 and shown at the exhibition ‘Works on Paper, a gift from Florence and Daniel Guerlain’ (2013). Here grimacing daisies recall the Baroque allegories of human temperaments and the stubborn talking flowers in Lewis Carroll's ‘Alice in Wonderland.’

Such pictures by the artist are on a large scale and are made to be unrolled like a scroll. In these works Litichevsky says he was inspired by paintings by members of the early 20th century avant-garde association ‘Jack of Diamonds’ and Mikhail Larionov (1881-1964) whom he discovered for himself in 1983, as well as the childlike paintings by Paul Klee (1879-1940).

In 2017, the Museum of Contemporary Art in Thessaloniki held a solo exhibition of his work called ‘Hypothetical Dances.’ And in 2019-2020 in Brussels and Moscow, Iragui gallery staged an exhibition called ‘The Intelligence of Flowers’ which was based on texts by the symbolist Maurice Maeterlinck.

Georgy Litichevsky explains: “For the exhibition in Greece, I created a series on the theme of dance, parodying the frieze of the Gigantomachy of the Pergamon Altar. The painting ‘The Parthenon Cannot Be Destroyed’ depicts how Baron Munchausen diverts Ottoman cannonballs from destroying the Parthenon, distracted by a belly dance. In another painting, Count Cagliostro wants to cross crocodiles with wolves to create ‘wolf-odiles,’ so that the Neva can acquire the status of the Nile. And here he meets Munchausen, and they exit through the underground streets of St. Petersburg into Neolithic caves with images. Yes, this is about the origin of art – but their communication is suddenly interrupted because the Neva waters start to rise, creating a flood... At the exhibition ‘The Intelligence of Flowers,’ I unfolded a 15-metre-long comic painting. In it, in the form of a dialogue between Tolstoy and Chekhov (with mention of Maeterlinck), an eco-aesthetic theory of ‘floratism’ developed. I invented this neologism. It means: all power to the flowers, as they are smarter than everyone.”

When Litichevsky's paintings are exhibited, they never behave well, leaping out of their frames, sometimes turning into objects, trashy dolls, and toys for hard-core Rastafarians. Litichevsky cancels all conventions and classifications, boundaries between genres are erased, and historical narratives merge into a single hallucinosis, gonzo journalism. In the contemporary world of lost illusions and posthumanist speculations, the artist's work has acquired a sudden and aggressive relevancy.