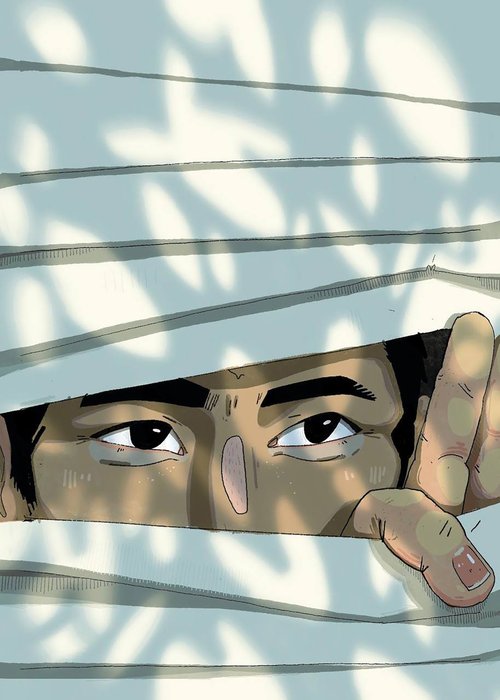

Katrīna Neiburga. Sologamy. Video screenshot. 2023–2024. Courtesy of the artist. Publicity photo

Latvian Artist Katrīna Neiburga’s Reflections on Sologamy

Established prize winning Latvian multimedia artist Katrīna Neiburga has a solo show at the Latvian Art Museum. In 2009 she received the prestigious Purvītez Prize, one of the country’s highest honours for individual contribution to the art of the nation.

Latvian artist Katrīna Neiburga (b. 1978) is perhaps best known today in Scandinavia where her works can be found in numerous contemporary art museums. In Russia she is known more as a scenographer where at the Mariinsky Theatre she created the video for Richard Wagner's Salome and for Tannhäuser at the Stanislavsky and Nemirovich-Danchenko Musical Theatre in Moscow. At the Perm Opera and Ballet Theatre she made videos for Sergei Prokofiev's ‘Dueña’.

Sologamy is a multifaceted artistic endeavour comprising video art, clips with different plots and periods, photographic collages made from self-portraits and genre scenes executed in all manner of techniques and colours, but always with one single protagonist, who is the author. Sometimes there are a dozen portraits mounted together in one space, each heroine looking at one other, showing a range of emotions, from surprise to admiration and confusion. Sometimes they are just double photographic portraits or video portraits with an intense gaze on the right and a detached, ironic one on the left. Her over a glass of wine; with Tarot cards. On a deserted Baltic beach, the video self-portraits run towards each other, foreheads collide, and then disperse in a reverse shot. The deliberate use of postmodernist techniques associates them with Andy Warhol (1928–1987) and his iconic diptych with portraits of Marilyn Monroe, and fifty portraits of the actress all looking at one another.

“I'm exploring solitude here,” the artist explains. “Traditionally, a woman who lives on her own is seen as an eccentric with cats, unkempt and lost. And in the contemporary sense, it is the exact opposite, she is a proud, self-sufficient, independent human being. I have tried to examine these myths in a mirror image, as if they were studying each other. And so, the artist studies herself. I was very attracted to the sound of the word ‘sologamy’. I found it when I already had the idea for the project. And then I came up with the context: I found the story of an American woman, Linda Baker, who arranged a serious formal marriage ceremony with a fiancé who never existed in reality. And there was the recent story of Indian blogger Kshama Bindu, who married herself in a traditional Hindu ceremony.”

In 2001 Neiburga started to work with various multimedia techniques, after receiving her master's degree in visual communication at the Latvian Academy of Art and since then she has risen to become the best-known multimedia artist in Latvia.

Like the French structuralist Roland Barthes in his book ‘Mythologies’, Neiburga conducts a thorough deconstruction of the myths of mass consciousness in each of her works. Barthes deconstructs an advert for washing powder as a means of deep cleansing of humanity and Neiburga deconstructs the healing tea mushroom kombucha, a popular craze of Soviet housewives in the times of so-called ‘developed socialism’, as a remedy for all diseases, the elixir of youth of the Brezhnev era. Barthes theoretically deconstructs cosmetics advertising, and Neiburga creates a project called ‘Hair’, a deconstruction of the meaning of hairstyles and close relationships with hairdressers in contemporary post-Soviet culture.

“When I decided to understand the phenomenon of kombucha tea mushroom, I put an advert in the newspaper. And after that began many adventures in Riga's residential neighbourhoods. It turned out that hundreds of people still grow this mushroom in three-litre glass jars, trade it, tell each other about its healing effect on their organism, even on their whole life. To loop this mushroom performance, I rented a tent in the centre of Riga and sold three-litre jars of kombucha. And had philosophical conversations with the customers. It's paradoxical, but the fashion for kombucha is making a comeback before our eyes!” says Neiburga passionately.

While the fashion for kombucha lived among the inhabitants of overcrowded five-storey residential blocks on the outskirts of the megacities of the late USSR, in the centre of Riga, among artists, writers and philosophers there was a fashion for the ideas of the Frankfurt School, the ideas of the Surrealists and Dadaists, the ideas of expanding consciousness through meditation, reciting mantras, ritual dances from pagan times, holotropic breathing, self-observation according to the method of the mysterious mystic George Gurdjieff. This fashion came to Riga from the neighbouring Estonian university city of Tartu, where these ideas were developed in the early 1970s by dissident intellectuals from all over the USSR.

At the beginning of 1993, inspired by the ideas of the Tartu semiotic school, Riga philosophers Uldis Tirons and Arnis Ritups began publishing a monthly intellectual magazine called Rigas Laiks (Riga Time). It is still very popular in Latvia, and the Russian version, published since 2001, has even reached Moscow and St Petersburg and you find it everywhere on the shelves of art collectors across those two cities.

In the mid-1990s, Tirons and Ritups travelled to London to meet the famous Buddhism scholar, philosopher and researcher of Freemasonry Alexander Piatigorsky. He was a remaining enthusiast of the various interdisciplinary studies of the Tartu semiotic school. They made an indepth documentary about him called ‘The Philosopher Escaped’, and recorded kilometres of interview tapes, which are still being transcribed, systematised and published in every issue of Rigas Laiks.

In the late 1990s, Piatigorsky was regularly invited to Riga to hold lectures, seminars and debates, both in academic classrooms and in Latvian forests. He talked about Buddhism, the Roerich family, the mystic George Gurdjieff, Freemasons, hallucinogenic mushrooms, his friends, the Tibetologist and religious guru Bidya Dandaron, who was imprisoned under Stalin for being from a Buryat lamaist family, and under Brezhnev for organising a tantra-studying group, about his youthful friend Yuri Knorozov, a Soviet philologist who deciphered the Mayan script. “Piatigorsky was an extraordinary human being, and it is impossible to stop talking to him,” says Neiburga.

From time to time the editorial staff of Rigas Laiks travelled directly to the spaces where she spent her childhood and youth. Neiburga’s mother, the famous Latvian writer and artist Andra Neiburga (1957–2019), was for many years the life companion of the legendary Latvian bohemian writer and philosopher Pauls Bankovskis (1973–2020). After Latvia's independence Andra Neiburga suddenly became rich and ran a real estate agency, and she immediately rented part of her property to the editorial office of Rigas Laiks to earn symbolic money.

“I have been in the artistic world since my childhood. Not only my mother, but also my father, Andris Breže, is an artist. He was very famous in the 1990s, his conceptual abstract graphic works developed the ideas of abstractionism, he experimented a lot with objects in the landscape,” says Neiburga. “But my mum used to say: don't go into art. Get a normal profession. Like a lawyer, for example. I didn't go to a children’s art school, as it is usual for future students of the Latvian Academy of Arts. And I was almost taken to law school. But I felt, no, I can't go there, I'll die there. I want to study art. So, I enrolled in the Latvian Academy of Art. Eleven years after my mother graduated.”

Would Neiburga ever become a professional film director? In 2016 after she won the grand prize of the Riga International Film Festival ‘Big Kristaps’ for her documentary film ‘Garage’ there was a sense that this might happen, but it turns out it is her eldest son who is studying to be a film director, Latvian cinema being on the rise, attracting good money from abroad. For Neiburga this is not an appealing prospect: “Cinema limits me to the rules of its genre. In cinema, I lose a lot of the freedom that is possible in video art. The cinema is interesting but too narrow for me.”