Jean-Jacques Gueron: the French supporter of Soviet nonconformists

The story of a successful businessman who became obsessed with Russian contemporary art.

How did a French trader from Nice manage to build an important collection of Soviet Nonconformist art without leaving France? The answer lies in what collector Jean-Jacques Gueron calls a stroke of fate.

His parents had arrived in France from Turkey in the 1920s. They had to earn a living and certainly couldn’t afford to collect art. Gueron was born in Nice in 1943 and moved to Paris where, after completing his engineering studies, he began working in a women’s fashions shop, together with his uncle and brother-in-law. Both those family members had begun collecting in the 1960s.

Gueron’s brother-in-law was interested in abstract art, while his uncle had a friend named Jean-Claude Gaubert, who was a fashion stylist and a Paris art world insider. It was Gaubert who introduced Gueron to contemporary art by taking him to artists’ studios in 1969.

His first acquisition was purchasing the work of Venezuelan artist, Mauro Mejiaz (1930–2000). At the time, Gueron knew little about art, but he was literally smitten, both by the artist, his paintings and even his studio, so much so that he bought Mejiaz’s entire works, which numbered around 100. It was the only time in his life that he asked his mother for financial help and it was that event which turned him into a collector.

Gaubert was astonished that a 25-year-old salesman would want to buy art, but he invited Gueron to a major exhibition at the Grand Palais in Paris in the Spring of 1972. The show was an annual event called ‘Grands et jeunes d’aujourd’hui’. They were strolling through the show when their attention was suddenly drawn to a small watercolour by Russian artist Mikhail Chemiakin (b. 1943). Gaubert was interested in it and Gueron eventually found the artist’s contact details.

Chemiakin had come to Paris in 1961, at the invitation of Dina Vierny (1919–2009), a Jewish émigré from Bessarabia who modelled for Matisse and Bonard and was the muse of sculptor Aristide Maillol (1861–1944) for his last 10 years. Vierny had organized a show of Chemiakin’s works in her gallery on rue Jacob, and offered him a 10-year-long contract to become a signed painter. Chemiakin, however, had come to France to break free from the restrictions of the Soviet regime and discover freedom. Vierny’s proposal fettered his intentions. Having rejected it, Chemiakin found himself out on the street. Gueron and Gaubert eventually found him in a shabby Paris apartment. They quickly became friends, and Chemiakin began introducing Gueron to other Soviet Nonconformist artists.

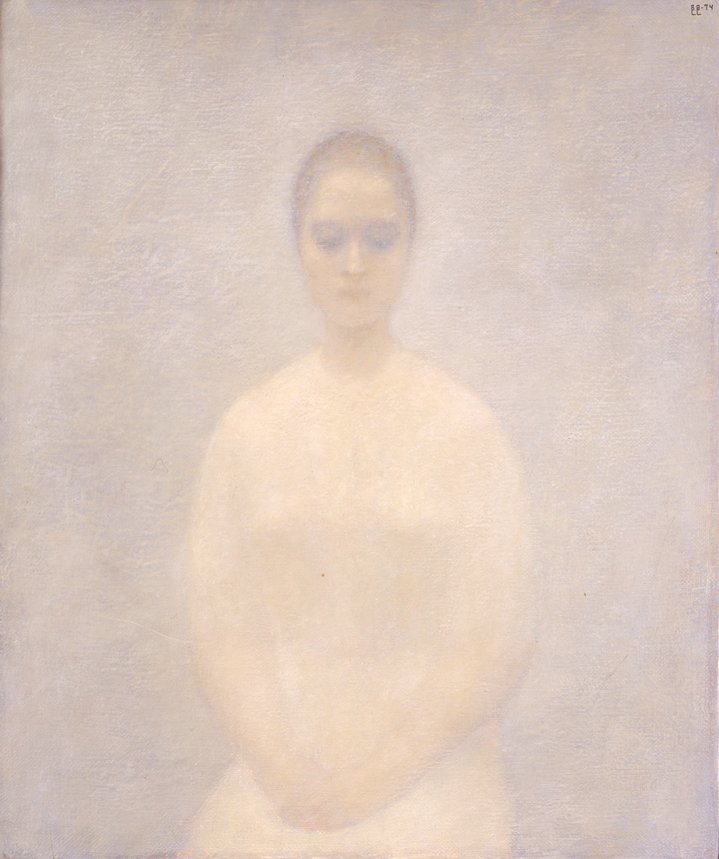

Soon, Soviet artists began flocking to Paris, and Gueron had a chance to meet them. Some of the artists he admired weren’t famous at that time, such as Lidiya Masterkova (1927–2008), whom Gueron met on his own.

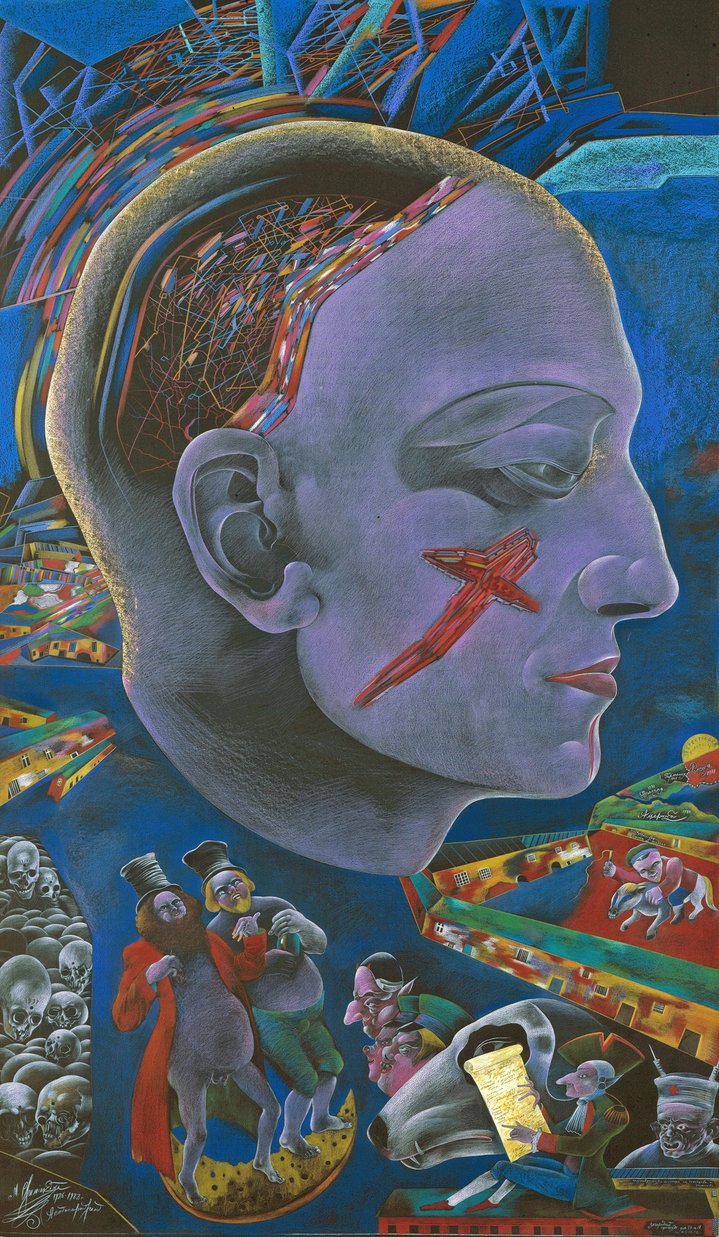

“My collection has two main pillars, and those artists are like day and night. They have nothing in common,” says Gueron. He is very fond of Chemiakin, especially the art from his Soviet period. Gueron was an active buyer of Chemiakin’s art from 1972 to 1980, after which the artist moved to the USA. The second “pillar” of Gueron’s collection is Vladimir Yankilevsky (1938–2018). He was among the last Soviet artists to come to Paris, but Gueron met with him shortly after his arrival and became his first and major collector in France.

Gueron managed to build his collection of Soviet Nonconformists almost entirely in Paris. It wasn’t until 1989 that he had a chance to visit the Soviet Union for the first time, mainly because most of his time was spent on focusing on his business.

In order to buy an artwork, Gueron needs a direct encounter with an artist. Moreover, he believes that people should aim to meet with living artists. “It pains me that instead people prefer waiting in long lines to see exhibitions of famous masters once they are dead,” he laments.

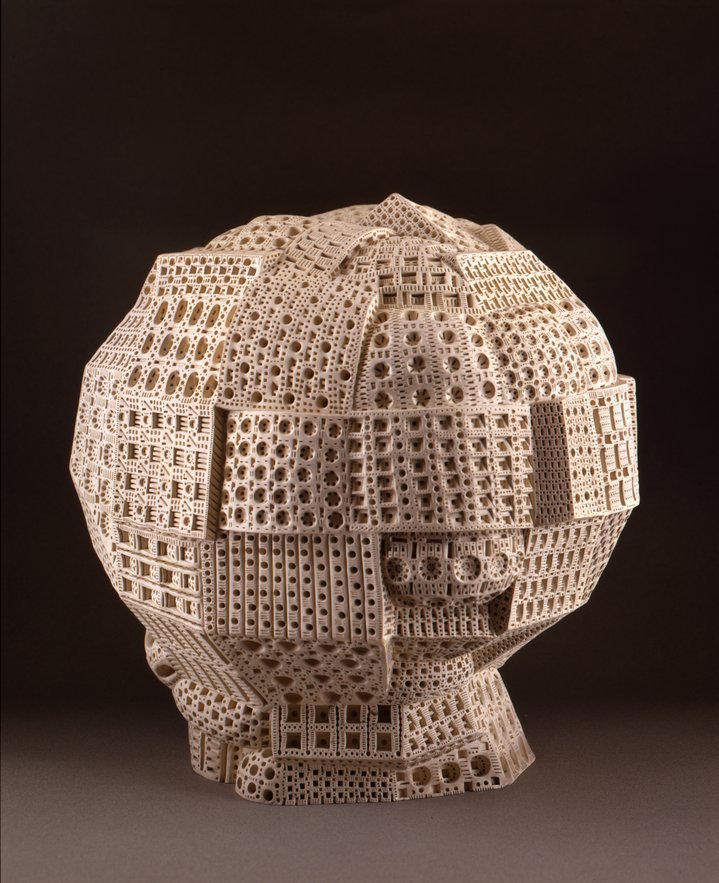

Gueron says that when he steps into an artist’s studio, he can immediately spot which of the many works on show he wants to hang on his own wall. However, Gueron has always has had one strong reservation. He has never felt the appeal of sculpture. “It might be a psychological issue, or perhaps I just never had an eye for it,” he says.

Other than that, Gueron doesn’t set any rules on buying art. What matters is that a painting should evoke strong emotions. It must, in his words, arouse a “coup de cœur”. The subject needs to speak to him, whether its message is tragic or light. In general, he is less interested in conceptual artists, but there are exceptions. Yankilevsky, whom Gueron admires is, without doubt a conceptualist.

Gueron has never sold any of his art works. “I wouldn’t have made a good gallery owner, because I can’t easily separate from the paintings,” he laughs. All art collectors yearn for their collections to secure a posterity. Everything in a collection is important: not just the famous artworks, but also the small “insignificant” pieces that testify to a moment in life, he says.

However, museums like the Centre Pompidou in Paris have never asked to acquire any of the works he has collected. Gueron says the first step in such transactions always has to be made by the museums. In Anglo-Saxon countries, museums and buyers cultivate relations with art collectors, but that is, according to him, not the case in France.

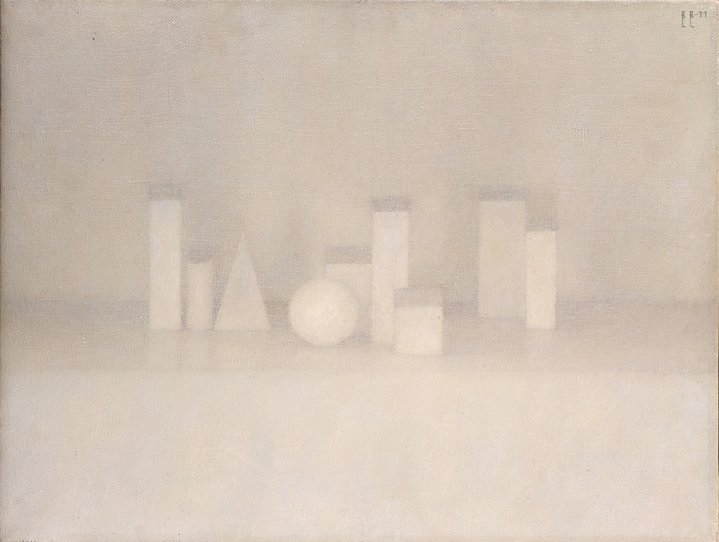

Nevertheless, Gueron has lent parts of his collection many times, including in Spain: first in Pamplona in 2002 and in Torrelavega in 2003, and in 2015 in the Nau Gaudi centre for contemporary art in Mataró. He is particularly proud of this latest exhibition and its catalogue, which includes around 120 works by Chemiakin, Yankilevsky, Oleg Tselkov (b. 1934), Aleksandr Arefyev (1931–1978), Oscar Rabin (1928–2018) and many others.

Since 1989, Gueron has visited Russia many times, but only on the occasion of his friends’ art shows and events, and never to buy art. If it hadn’t been for the Soviet Nonconformist artists, he would have collected South American or Eastern European artists, or the Surrealists. But having found Russian art, he has enjoyed the journey greatly. “If I hadn’t found Mikhail Chemiakin’s address at the exhibition at the Grand Palais in 1972, I wouldn’t have existed,” is the way he puts it.

Gueron Collection