Jānis Zuzāns: between a casino and a museum

An art collector from Latvia has opened a private museum in the heart of Riga. Despite the complex relationship between Latvia and Russia, here artworks from both countries co-exist in perfect harmony.

Jānis Zuzāns is one of the top ten richest people in Latvia. He is the biggest art collector in the Baltics, sponsor of the prestigious annual Latvian Art Prize in honour of the artist Wilhelms Purvitis (1872–1945) and founder of the Latvian Academy of Art. There are only two permanent experts on the jury - Jānis himself and Mara Lace (b. 1954), director of the National Museum of Art; guest experts change every year. He represents Latvia on Tate’s Russian and Eastern European Acquisitions Committee. Despite such esteemed posts, in the public’s opinion and that of Latvian intellectuals, he is a controversial figure, because Zuzāns made his fortune in the business of slot machines. These are locally dubbed “one-armed bandits” and he owned the country’s very first casino in the Post-Soviet era.

In September 2020, Jānis and his wife Dina opened the Zuzeum Art Centre on the outskirts of downtown Riga, in a late 19th-century restored factory building in the style of a loft. During the first months of its existence, it operated on an appointment-only basis, due to the COVID-19-related lockdown in Latvia. Its exhibition space is 3,000 square meters and the collection includes more than 2,000 works by artists from almost fifty countries around the world. And one of its largest parts is a collection of Soviet unofficial and contemporary Russian art. Prior to the opening of Zuzeum, the couple had already shown works from their collection in their gallery Mukusalas Makslas over the past decade.

The Zuzāns’ collection grew out of a few spontaneous purchases in the 1990s: Jānis was very interested in Indulis Zarinsh (1929–1997), a living classic of Latvian art. Jānis recalls how he saw the painting ‘In the Artist’s Studio’ at the last exhibition that took place while the artist was still alive. That work now hangs today in the couple’s bedroom. And Dina really wanted to acquire for their home a landscape by Liga Purmale (b. 1948), which she had seen by chance in a local gallery. “For the first ten years, it was just a hobby, but suddenly it turned into a real passion and we decided to collect seriously,” says Jānis Zuzāns.

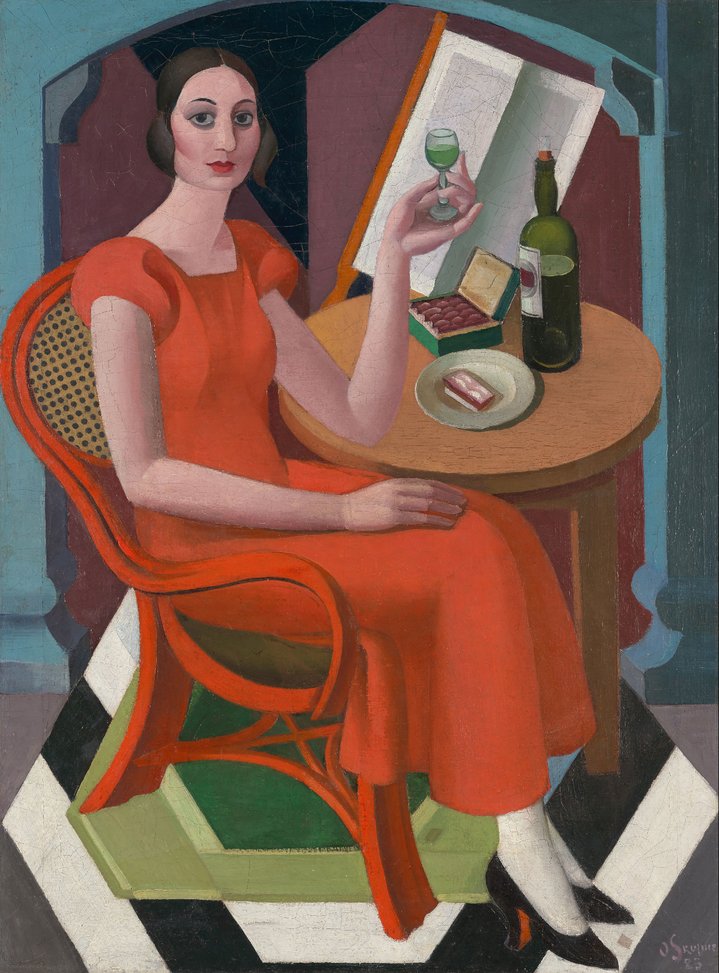

Jānis was a great admirer of French modernism, Picasso and Braque and, in the early days, he was fascinated by the works of avant-garde artists of the First Republic of Latvia (1918–1940). The heyday of Latvian avant-garde painting was from 1919 to 1927. At that time, many Latvian artists even lacked money for paints and canvases and now works by such masters as Niklavs Strunke (1894–1966), Romans Suta (1896–1944), Uga Skulme (1885–1963) and Jekabs Kazaks (1895–1920) are rare and extremely difficult to find. And those that are available have already been collected by museums. But this betrays the excitement that the Zuzāns love.

In the summer of 2017, the Zuzāns showed their collection of Latvian paintings at the National Museum of Art in Riga. The exhibition ‘TOP no Top / Top of the Top’ covered 200 years of painting development in those geographies which are now called Latvia. “I heard conversations about these artists as a child, I saw their works in the art magazines of the First Republic, which my father used to buy. Our family had money, my father worked as a manager in a department of a large grocery store in Riga, meaning he ‘sat on the deficit’,” says Jānis frankly. Seven years ago, at Art Basel, on the stand of Moscow’s Regina Gallery, Jānis got into conversation with Mikhail Ovcharenko, a young but, in his words, erudite and active art dealer, the son of the famous Moscow art dealer Vladimir Ovcharenko.

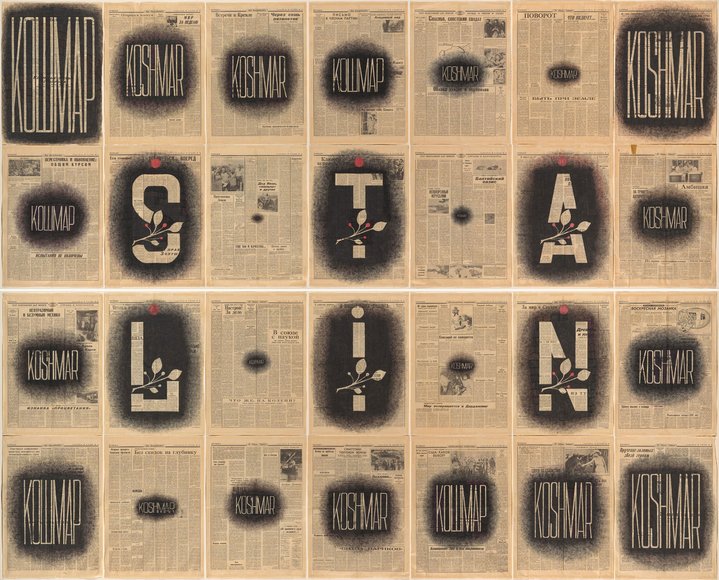

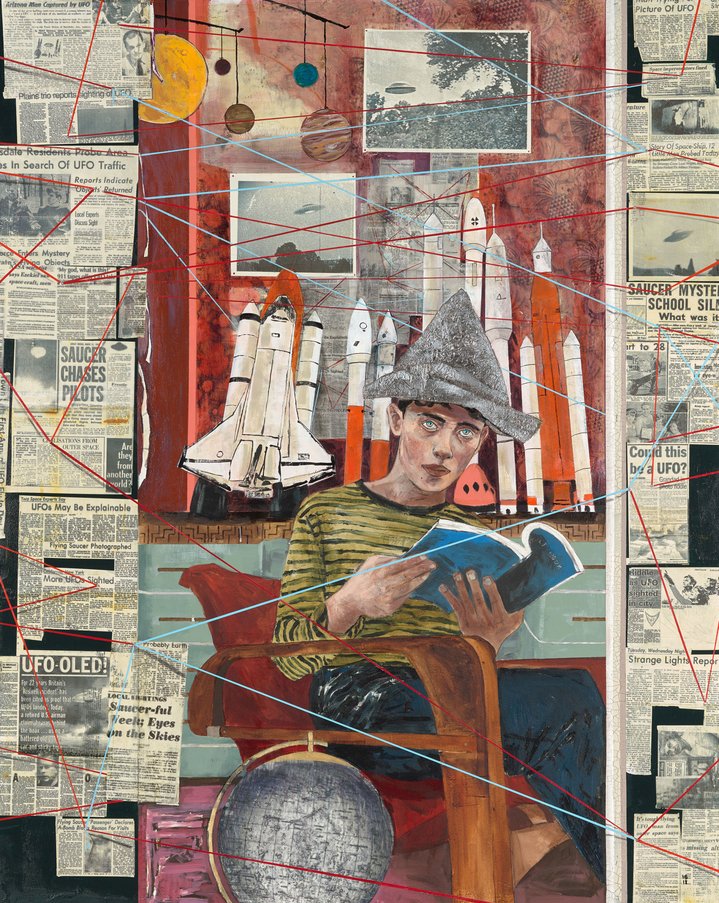

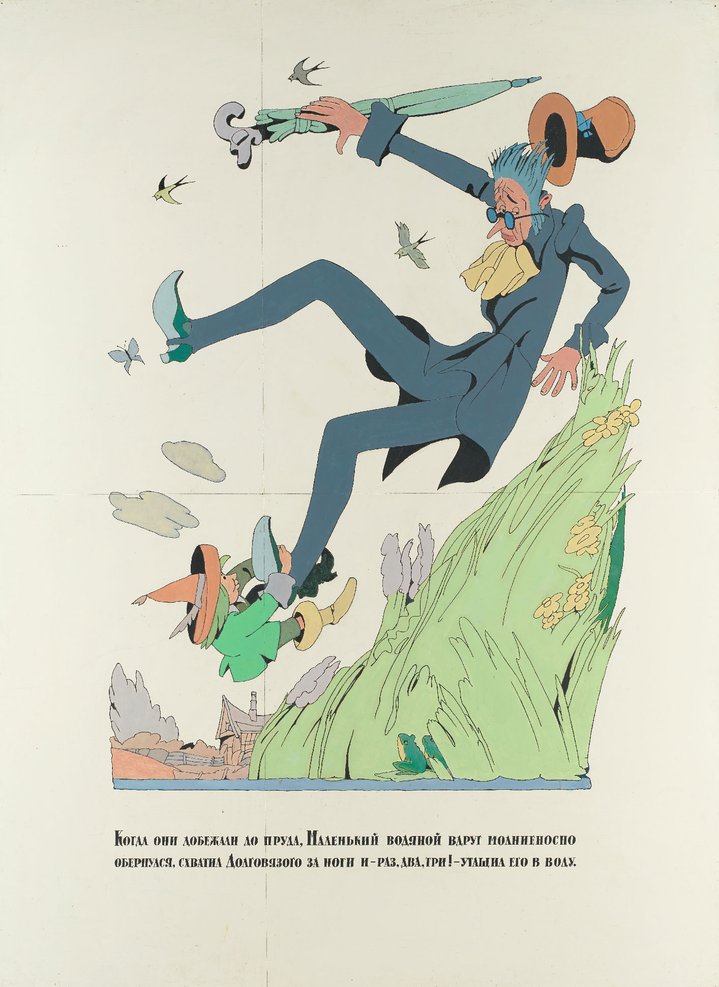

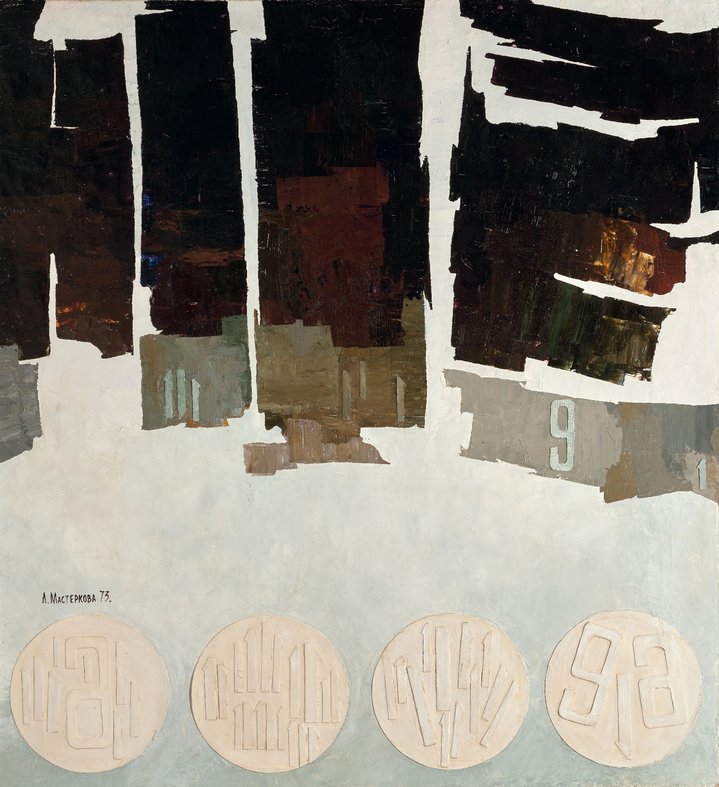

“He told me a lot about unofficial Soviet art of the '60s and '70s. And at this time, I came up with an idea to make a collection of underground Soviet art. I wanted to make a comparison: there were also non-conformists in Soviet Latvia at that time, but they weren’t banned. In Moscow, they used to bulldoze exhibitions. By the way, I have works from that famous Bulldozer exhibition! I’m generally interested in people’s confrontation with different political systems. But I am especially fascinated by the subtle language of artistic protest: Oscar Rabin, Lydia Masterkova, Vladimir Nemukhin, Erik Bulatov, Dmitry Prigov, Ilya Kabakov.” Since then, Mikhail Ovcharenko has been helping him put together a collection of works by these artists. Jānis has decided to hold a major exhibition of Russian art from the 1960s to the 1990s in Riga next year. He has not decided on a name yet, but there will be a couple of hundred works ranging from Oscar Rabin (1928–1918) and Anatoly Zverev (1931–1986) to Oleg Kulik (b. 1961) and Anatoly Osmolovsky (b. 1969) (declared a foreign agent by the Russian authorities).

Jānis Zuzāns is often criticized for his gambling business. They say, “People sometimes lose their last coin and families go bankrupt because of addiction to games, while he enjoys his art!” When hearing such accusations, Jānis calmly retorts “We offer a choice and everyone decides for himself whether to go to a gambling hall, or an art gallery.” But now, he risks making new enemies among his countrymen for his passion for Russian art, as well. Latvians are wary of Russians because of 20th century history how the Soviet Russians occupied Latvia, destroyed its independence, tens of thousands of people were deported to Siberia and the North, many of the deportees died. Almost every Latvian family had a relative, close or distant, who died during deportations. This is echoed even decades later. After the annexation of the Crimea, the attitude towards the modern, new Russia in Latvia is extremely cautious. In early March, the news about Russian billionaire Pyotr Aven’s purchase of a building opposite the National Art Museum of Latvia to house and display his huge collection of paintings and porcelain was discussed in the Latvian press. Most observers wrote about “Putin’s hand from Moscow” allegedly “visible” behind this purchase and the billionaire’s intentions. Many Latvian bloggers were of the same opinion. Although Aven assures that he primarily cares about the tourist attractiveness of Latvia, the homeland of his grandfather Jānis Aven.

“In my family, too, there were survivors of the occupation”, Jānis says. “But, you know, many Latvians who survived and returned from Siberia say: if there weren’t good Russian people there, they wouldn’t have survived. Don’t take the bias of a small group of our nationalists as a policy of the state. I don’t feel wary of my interest in collecting and exhibiting Russian art.” Jānis calmly talks about the fact that Russia has been on this territory for almost 300 years. That is why it is interesting to compare Russian art from the Soviet period with Latvian art: the two developed in parallel, yet they were very different. Artists even in Soviet Latvia did not feel the “onslaught of politics” from above. Jānis was surprised and perplexed when he realized that even many professional art critics in Latvia, academically educated people, know very little about Russian contemporary art and almost nothing about the unofficial Soviet art of the 1960s and 1970s, with the exception of Ilya Kabakov (b. 1933). “But when I talk about Oscar Rabin, Komar and Melamid, Leonid Sokov or Dmitri Prigov, they just open their mouths in surprise. They hear these names for the first time. And these are internationally recognized artists!” This is also the reason why he wants to show them to the Latvian public.

Zuzeum art centre