A video work by Irina Nakhova, which contained footage of street protest rallies, was censored from a museum exhibition in Venice. A year later, she unveils it in Moscow.

The artist Irina Nakhova (b. 1955), one of the standard-bearers of Moscow Conceptualism, prefers to transform reality around her rather than conform to it. As a teenager, she was introduced to a prominent Moscow Conceptualist named Viktor Pivovarov (b. 1933), who encouraged her interest in contemporary art. “The best and most productive time for Russian artistic community was in the 1970s and 1980s, when people were very supportive of each other,” she believes. “There was no gender [or] age discrimination. I was treated as an equal. Older artists never ‘mentored’ us, they taught us through example,” she told me in a recent Skype interview.

Irina enrolled in Moscow’s Polygraphic Institute and, upon graduation in 1978, she made a living illustrating books. In the 1980s, she pioneered the ‘total installation’ genre, transforming her room into an immersive artwork. For her, this was a refuge from the suffocating social climate of the final phases of the Soviet regime. “I did it for myself, because I felt a need to transform my living space. I invited only close friends to see it. Back then, I did not think of it as of an important breakthrough in Russian art.” Each installation only lasted a couple of weeks.

Sotheby’s first Moscow auction in 1988 brought the USSR’s underground art into the limelight, including international recognition for Nakhova. In 2015, she became the first female artist to represent Russia at its national pavilion at the Venice Biennale.

Her work has covered a broad range of themes, from gender issues to the tragic history of Russia and her own family: her grandfather was executed during Stalin’s Great Terror of the late 1930s. Since the 1990s, she has taken an interest in new media. Her works are often equipped with motion sensors: they interact with approaching visitors and even strike up conversations with them.

She always takes the architectural properties of the venue into account. “An installation should always be site-specific. Otherwise it is something different - an object, or a sculpture,” she says. Yet, despite her ever-growing interest in new media, she never abandoned painting.

“When I paint, I perceive the passage of time in a totally different way.” The process of painting for her is vital, and somehow akin to psychotherapy or meditation. “When I work on a video or an installation, I aim at a certain pre-planned result. But when I paint, it’s not like that. There’s no goal to achieve and my head should be perfectly clear. Painting adds time to one’s life, while all other activities take the time away from it,” is the way she puts it.

Since the early 1990s, Nakhova is based in Moscow and the U.S. “I have never actually moved to America,” she says. “I just split my time between my two homes.”

As well as many other Moscow artists, she took part in anti-Putin rallies after the rise of protest movements in 2011--2012. “As a citizen, I try to keep track of the processes taking place in our society.” Many of these rallies in Moscow were brutally dispersed by the police. Hundreds of protesters were arrested. Nakhova started filming these scenes of rebellion and violence right from the start, without having any particular project in mind. Her installation ‘Repairs’, shown at the Moscow’s private Stella Art Foundation in 2012, included some of this footage, as well as her ‘Green Pavillion’ show at the Venice Biennale in 2015.

Nakhova was later invited by the Moscow’s State Pushkin Museum to take part in a media art exhibition that it and the Stella Art Foundation were preparing for the 2019 biennale. The show, inspired by Tintoretto, was to take place in a deconsecrated church, in which condemned Venetian criminals in the past had to spend their last night praying before execution. Nakhova had developed a three-channel video installation for the site, which included footage of protest rallies in Moscow and Paris.

She felt it was a right homage to the most expressive painter of the Venetian Renaissance. Nakhova points out that “Tintoretto was a painter of crowds and his works are always full of drama”. She takes the protests out of their up-to-the-minute political context by slowing down the movements and covering the image with semi-transparent patina. As an artist she focusses on human emotions, on the faces of people thrown by fate to the different sides of the struggle. “I like to observe how ordinary people get involved in politics, and thus, into history,” she says. The process of making photo and video documentation allows her to focus on the details one never notices during the event itself. “I like to watch the transitory turn into the eternal,” is her explanation.

A few days before the opening the representatives of the Pushkin Museum of Fine Art informed Nakhova that the footage showing the protest would not be shown, blaming that on the Italian side. “I was never able to find out what actually happened and why,” Nakhova admits. “That work was ruined, as it lost its only connection with the present. It was instead turned into a pretty candy,” is the way the artist saw it.

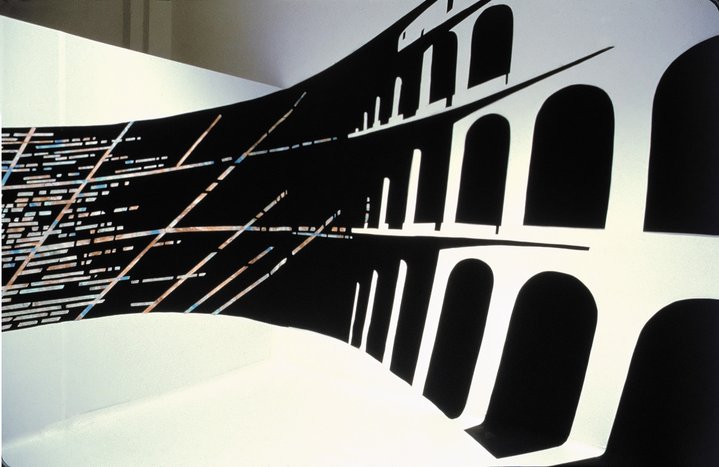

Disconcerted, yet unabashed, she decided to develop the censored part a separate project to which she added footage of anti-Brexit rallies in London filmed in September 2019. She used one frame of her video as a base for a four-part painting. The resulting installation called ‘The Wall’ will be shown in September at the Moscow’s private pop/off/art gallery. Due to the disruption of international flights caused by the lockdown, Nakhova won’t be able to attend the exhibition herself. Nevertheless, its timing could not be more appropriate. With the BLM movement on the rise in the U.S. and a potential political upheaval in Belarus, Russia’s closest neighbour, Nakhova’s inquisitive, compassionate gaze invokes much-needed reflection amidst all the sound and the fury.