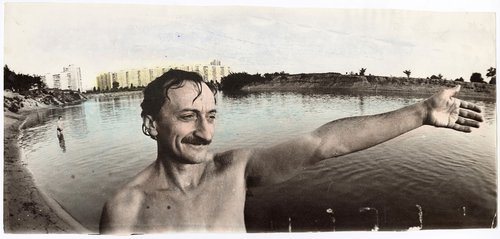

Sergey Bratkov. Qutting Smoking, 1995–2022. Inkjet print on AluDibond, lightbox. 130x200 cm. Courtesy of Volker Diehl Gallery

Heartbreak in Berlin. A New Exhibition of Kharkiv-born Artist Sergey Bratkov

Sergey Bratkov's latest exhibition opens at the Diehl gallery in Berlin on the 9th of December, in the midst of an unimaginable geopolitical context. The exhibition, called Heartbreak, is a retrospective consisting of photographs and videos from the 1980s till 2010s and will also showcase a new work created especially for the event.

Sergey Bratkov moved to Berlin in the summer of 2022 after living and working in Moscow for the past two decades. Already now in his seventh decade, behind him are numerous solo and group exhibitions across the Ukraine, Russia and worldwide. He represented both Russia and the Ukraine at the Venice Biennale, in 2003 and 2007 respectively, and his work was shown at Manifesta 5 in San Sebastian in 2004. What is the story behind his exceptional rise to international success?

It all started in his childhood at the Bratkov family dacha. The older generation of Kharkiv underground artists, such as Boris Mikhailov (b. 1938), Oleg Malyovany (b. 1945) and Oleksandr Suprun (b. 1945) were often guests at Sergey’s parent’s dacha, and it gave him a precocious taste of the art world. In his early twenties, together with his brother, he would organize local discos for which he would also design the interior decor, and in one interview Bratkov says it was in 1984 that he first became an artist when looking for a permanent space for a disco. That project did not work out but for the first time ever he understood the social and artistic importance of space. In that same year he made the ‘The Cherry Orchard’, a series which depicted the social and economic collapse of places where Russian playwright Anton Chekhov had written the eponymous play. Bratkov´s characteristic novelty, as opposed to the movement later called the Kharkiv school, was the search for domestic situations, painfully perceived by the author as weird and dysfunctional. There was his early mini-series about the funeral of a schoolteacher on a collective farm. With a freshly dug grave beside the school, filth, songs accompanied by guitar, and a pervading sense of being out of place. What was happening there, and why had things become so bad? The participants of this scene did not know why, and are tormented by the very fact of their own presence in this situation.

Sergey Bratkov. From the series Spell, #1, 2014. C-print, 34x51 cm. Courtesy of Volker Diehl Gallery

Two years later Bratkov got married, and on that same day as his wedding , 26th of April 1986, there was a disaster of unprecedented catastrophic scale at Chernobyl nuclear power station. The artist recalls it today, ‘My wedding was like in a movie. In Kharkiv. We were celebrating at my parents' dacha. My brother went to say goodbye to some of the guests and by chance was confronted by a gang of thugs who beat him up. They broke his jaw. Some were former convicts. Quickly the police found them and there was a trial. But just a week later I got a summons to go to Chernobyl. I had graduated in rocket engineering including missile maintenance so I imagined it must have something to do with the decontamination of the Chernobyl exclusion zone. As I said my goodbyes, I took a picture of myself with my brother and his daughter. It was a family picture... I arrived in Kyiv, where they put us up in a dormitory, but then for some reason they sent us all back to Kharkiv. They did not call me up to go to Chernobyl after all.’

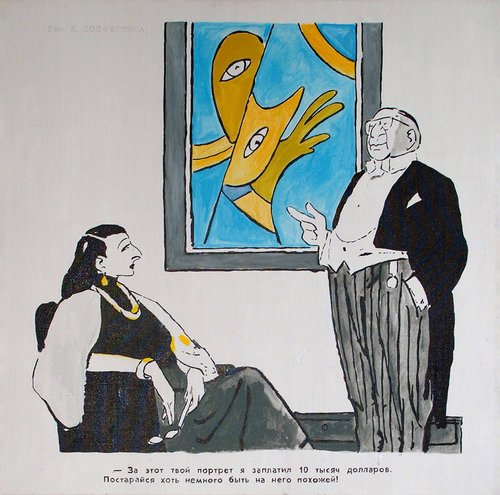

Around the same time, in 1986, Bratkov became a co-founder of the group ‘Litera A’. There followed a period of creative output of expressive paintings, oil on canvases. It was Perestroika and Glasnost, there was a wave of western interest in contemporary art from behind the Iron Curtain, and the establishment of international relations. This was all already underway inside the USSR. The resulting art sales, which were at that time mainly in Germany, enabled Bratkov to create a financial cushion and establish his independence.

During this brief period, Bratkov had never actually stopped taking photographs, but he was searching for ways out of the traditional methods of photography that had existed in the late Soviet Union, attempting to propel the medium into gesture and performance. His first photographic exhibition took him to the city of Cheb in the Czech Republic in 1989. It was during the Velvet Revolution. Around the same time, he also started making objects such as quilt covers sewn from photographs. When his grandmother passed away, he tied her personal belongings to a pole, took photos, poured them into concrete and buried them. Bratkov, together with Boris Mikhailov and Serhii Solonsky (b. 1957) showed their work to the public in 1991 at a group exhibition at the Opera House in Kharkiv. It sparked off a period of close friendship and intense collaboration between the three men.

He began to turn away from painting. As Bratkov puts it now: ‘The time for painting was over. There was an economic full stop ... and, more importantly, it was a time, the beginning of the 90s, when everything sped up, all that sitting in the studio and painting. There was a sense you had to respond quickly to the times. Photography was an opportunity to respond quickly. And we were interested most in questions about the Soviet past. The history of memory, relations on a national level, that was all connected.’

In 1993, the Rapid Response Group, chiefly a photographic project, materialized: Mikhailov, Bratkov, Solonsky, later joined by Vita Mikhailova. Their first major project together was ‘Transsvyaz’, a kind of teleconference with the addition of photography and performance between the United States, where Mikhailov was living at the time, and Kharkiv, where Bratkov was.

At that time Sergey kept his studio in the attic of an old house, and in 1993 he turned it into the ‘Up Down Gallery’, a not-for-profit project as at the time commercial galleries were only just beginning to exist in post-Soviet Russia. An exhibition of Serhii Solonsky’s work was the first to be announced and in the first year Bratkov showed a new series about homeless people called ‘Frozen Landscapes’. The works were printed on card, frozen in blocks of ice and suspended from a rope, with water dripping onto the floor as it melted. The ice fell off with a huge thud. The cards themselves, once dry, adopted the quality of sculptures. ‘Up Down’ is also where the posthumous ‘Litera A’ exhibitions were held.

In 1994, Rapid Response had an exhibition in Kharkiv Art Museum called ‘Ukrainian Photographic Expressionism’. The artists did a performance in which they wrapped themselves in bandages, after which the exhibition was suddenly closed down. The standout works of that time are a reflection on identity. There was ‘Spitting on Moscow’, where a zoo camel is taught to spit in the direction of the former capital of the USSR, or ‘The Three Letter Box’, which examined the readiness of people to instantly mimic the circumstances of the new state. The band members were all about provocation and interaction with their environment. At the same time, they did completely different things in their solo projects. For example, Mikhailov was showing his social-meditative series ‘Near the Land’ at the XL Gallery in Moscow.

Sergey Bratkov. Portrait with father, 1995. Inkjet print, 30x30 cm. Courtesy of Volker Diehl Gallery

‘When it all spilled out in the early 1990s, a lot of young people rushed into social reportage, and then time passed and so arose the question, what to do then? And then there was the example of Boris Mikhailov, who said about his work: tear it up, re-connect it, comb it into the redness of the swollen social body’, Bratkov recalls.

Rapid Response carried on until Mikhailov left for Berlin. Their last project in 1997 was the series ‘Guard of Honour’. It is a kind of ironic reflection on post-Sovietism. While in Moscow, the group members had noticed that there was no longer a guard of honour with bayonets near the Lenin Mausoleum. So, they took knives from the canteen and began marching in front of the mausoleum. Naturally, they were arrested.

By this time the money he had initially earned from selling paintings had run out. To earn a living, Bratkov was shooting portraits on commission, often keeping something aside for himself. Then, in Moscow, he went to work in an advertising company, cooperating with glossy magazines, notably Playboy. On the one hand this added glamour to his photographic palette and, on the other, it gave him professional chutzpah and opened some doors.

He drew on similar experiences with a pivotal project in his career called ‘Children’ executed in 1999 and 2000. This intimidating, almost glossy photo-shoot of kids, shot in worn interiors of Kharkiv homes with the permission of the parents, was exhibited in Moscow in 2000, at the Regina Gallery, and caused a major stir in the public. At the same time, it marked the start of a multi-year collaboration between Bratkov and entrepreneurial gallery owner Vladimir Ovcharenko. From the turn of the millennium, Sergey Bratkov gradually found himself becoming one of the most important contemporary artists in the Russian cultural scene.

He went down parallel paths of documentary photography and staged portraiture. Important documentary projects of the noughties include ‘My Moscow’ (2002) and ‘Volcanoids’ (2004), a kind of wild ethnography; ‘Ukraine’ (2009), a story of youth, drive, danger, and nonchalance against a landscape with a post-apocalyptic mood. He also made videos and received one of Russia's two most important contemporary art prizes, the 2009 State Innovation Award for his work ‘Balaklava Courage’.

And an example of staged social directing is a series created in a Kharkiv home for the elderly after the sinking of the submarine Kursk. Here, Bratkov filmed old people who had served in the Russian navy. In addition, in 2003, he filmed a series titled ‘Metallurgists’.

If in the 1980s Bratkov was thinking in individual works like an artist, in the 1990s, he started thinking more like a photographer in terms of a series rather than unique one-offs. And then, as he put it, he had worked this serial agenda out of his system by the mid 2000s. And although from time to time he will still mount an exhibition dedicated to a series of works, as an artist he has moved towards making statements in which photography is only one of his methods of expression.

In 2013, the work ‘Leaving to Forget’ appeared, in 2016 ‘The Next Station is Barricadnaya’, and in 2019 ‘You Don't Fly from Restaurants to Outer Space’. Huge black and white photographs or collages on photographic canvas, complemented by neon or acrylic, became his signature pieces in this decade.

Since the late noughties, Bratkov's work has been deeply chiseled by the growth of frustration, which is evocative of the thinning of the social fabric in Russia, where the artist was living at the time. His most recent exhibition in Moscow which took place just last year was called ‘Was/Is’. What looks from the outside like the prosperity of the Russian capital is presented as a thin film, masking an uglier reality, ruin and ultimately hopelessness. Of course, a few of Bratkov's projects during recent years beg to be interpreted post factum as a premonition of the future war; but this is a stretch. However, as an artist, he has captured the emotions that spill over into the atmosphere, and this resonates in his work. If you view them consecutively, you can see a cumulative effect.

Bratkov has always exhibited in Ukraine, including a solo show called ‘Ukraine’ at the Pinchuk Art Center in 2010 and, in the same space, a group show titled ‘Guilt’ in 2016. He still regularly takes part in projects in other European and American countries. Bratkov is no newcomer to the Volker Diehl Gallery in Berlin, where his work was shown in 2013. Now, a new round of collaborations has come about, in which the artist is reassembling his early history from its shards, and at the same time breathing life into a new one.