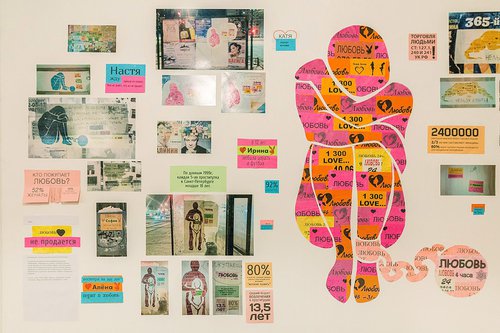

Olga Grotova. The Friendship Garden, 2023. Studio Voltaire. London. Courtesy of Olga Grotova and Studio Voltaire. Photo by Zoe Maxwell

Grotova on Feminism, Gardening and Memory

Studio Voltaire, a not-for-profit venue in a repurposed Victorian era mission hall tucked away in South London reaches out to both local communities and international artists from outside the mainstream. During her artist residency, Russian artist and poet Olga Grotova has brought stories from her own family history, one that is familiar to many Russians and yet is still taboo. Revealing these stories to international audiences they also need to be told closer to home.

In Britain we call it sweeping things under the carpet. At a public discussion last month between eminent art historian Griselda Pollock and Olga Grotova (b. 1986) as part of her current practice-based research project ‘The Friendship Garden’ at Studio Voltaire, a Latvian artist who happened to be in the audience, asked a question ‘on behalf of a friend in Latvia who is also an artist’. Her friend had thought about exploring memories relating Stalinist camps in her work but said that she was simply too afraid to do this. Grotova’s video ‘To My Daughter I will Say’ about her and her mother’s journey to the all-female gulag in Kazakhstan in which her great-grandmother Klavdia and grandmother Marina had been interred for twenty years, has just been completed. After its showing in London, Grotova would like to share it with those whom she met on her journey and perhaps who were shaped by the same fate in the Kazakh camp but there are limits. Grotova admitted on the surface her video is just about gardening and women so it can be seen as unthreatening, but such invaluable, open conversations around the work would be hard to imagine in Russia or Kazakhstan. For people whose family members were affected by the gulags it is often too painful, and for the authorities this is a history they want to write (or write out) themselves.

There is something of David and Goliath with softly spoken Olga Grotova and her art practice. At Studio Voltaire, in a leafy south London suburb you find her 20-minute video shot on 8mm film in a tiny dark brown walled room hung with some of her soil paintings. I sat there watching it through several viewings and no-one else came in. It is fragmented, pieced together a bit like memories are with a haunting soundtrack, you immerse yourself in the light and nature she has captured, her art is about aesthetics as well as politics. But for Grotova it is far more than the film. Art practices today have become more than production or process, it is art in an art ecosystem and how it connects with people and how art has the power for social change. When dealing with past traumas, Pollock talks about how, in English, we can speak of ‘withnessing’ something rather than witnessing. We were not there, but we can honour and explore the past by engaging with it ourselves and artists can help us do this. It is cathartic and in this lies the power of Grotova’s art.

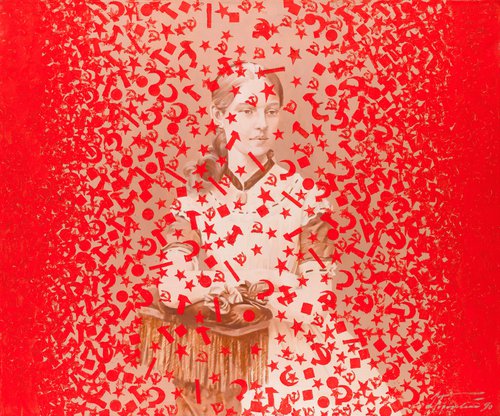

The Goliathan scale of the trauma is well known even if individual stories are rarely shared in public or in private. The experiences of Grotova’s family were repeated all across the Soviet Union, a vast container of millions of lives which endured traumas long since buried and forgotten or washed away. Women in particular need to find their voice to express their sense of this collective past. As Pollock pointed out during the discussion at Studio Voltaire, in the West it is stories about experiences in Stalin’s camps written by men and about men which are best known, although there are memoirs by Ginzburg and Kersnovskaya they do not get such an airing. Sharing these stories from a female perspective is something particularly topical now, the memoir ‘In Memory of Memory’ published just five years ago by Maria Stepanova pieces her family history together from old photographs, letters and diaries, it is a history which was not handed down first-hand through anecdotes, she has to build the story herself as a writer.

There is a sense that Olga Grotova’s most important work is yet to come. She plans to return to the camp in Kazakhstan. Called ‘Point 26’, referring to its geographical location, it was closed after the death of Stalin, although by then it had grown into a huge undertaking with thousands of people working in it. When the camp was closed, buildings knocked down and archives burnt, the garden remained and some former prisoners and guards stayed on and it was assimilated into a collective farm which produced abundant fruit – locals later nicknamed it Raspberry Village and for a rouble went there to get a bucket of raspberries. Grotova’s dream is to re-establish the garden as kind of living memorial and bring different communities together, it is a kind of soft art activism she describes as being ‘implanted’ now in her practice. It is no small task, though, involving the upward struggle of looking for funding and also dealing with contemporary Kazakh cultural strategies.

It is cultural investment that desperately needs to be made and support is crucial. It was George Orwell who said something about destroying a people if you deny or obliterate their own understanding of their history. Telling stories about the past which have been hidden or repressed in our societies or communities, serves not just as a kind of resistance in the present, it is a means of our survival. If, for millennia, art has told stories or acted as a catalyst for others to open new dialogues, it seems that today this is as relevant as ever as an agent for change for the better. There are parallels between present and past. A line in the film reminds us that the women in the camp took to gardening together as an act of self-survival. It empowered them to carry on and build something good in the midst of such inhumanity.