Grisha Bruskin: between the archaic and the modern

A solo exhibition of this artist, who found his own philosophical approach to history and myth, is opening at the State Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow.

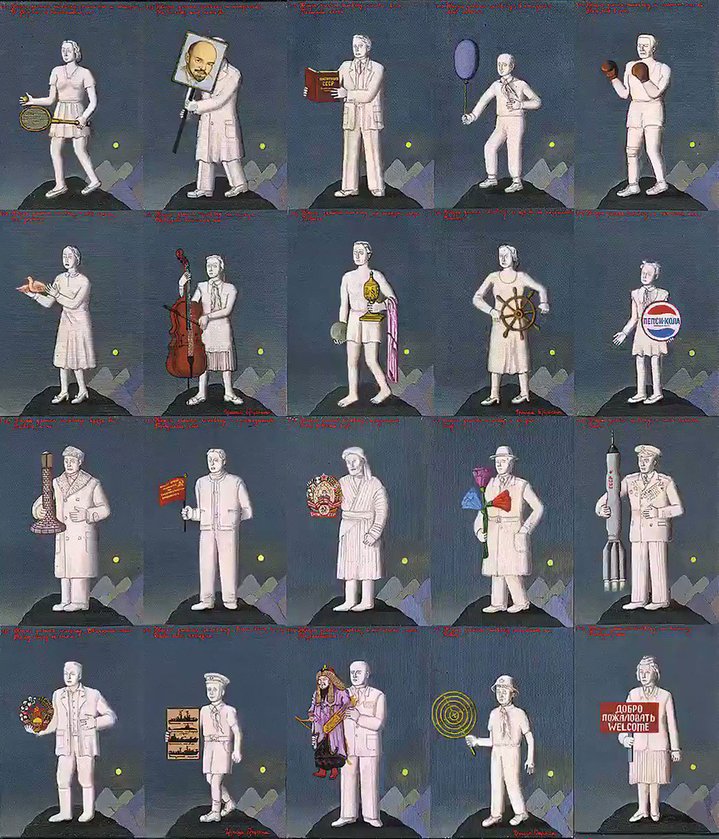

On July 7, 1988, Sotheby’s ‘Russian Avant-Garde and Contemporary Soviet Art’ auction took place in Moscow and the rules of the game changed forever. To the enormous surprise of the artists and the Russian art community as a whole, all of a sudden, there were collectors ready to pay substantial sums of money to acquire works of contemporary art outside the canon of Socialist Realism, which had been in strict force since the 1930s. On top of this, the real sensation at the auction was ‘Fundamental Lexicon’, a polyptych of 32 small canvases by Grisha Bruskin (b. 1945), estimated in the catalogue at £17,000 and eventually hammered down after heated bidding for £242,000. At the time, this was seen as a staggering sum and it caught the attention of the international media and thrust Bruskin into the limelight. However, as Andy Worhol's famous saying goes, fame only lasts 15 minutes, if it is not underpinned by the kind of authentic and unique vision of the world which an artist builds over his or her long career.

As an artist, Bruskin’s seems to embody the Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben’s image of modern man: a man whose modernity depends on the fact that he does not appear to be modern, because he steps aside from modernity, in order to have a proper look at it; to scrupulously analyze it. What is important in so doing, explains Bruskin, is that time becomes a continuum without a yesterday, a today or a tomorrow. The artist calls this “the collusion between the archaic and modernity”. The act of artistic creation lies in the ability of soaring upwards, only to look down at history from above as a sequence of simultaneous events. Contrary to what some might think, the artist’s role is not that of myth maker. The artist is well aware that even myths are subject to death. For Bruskin, the artist researches through the lenses of his own artistic vision how myths are born, live and die.

At root level, Bruskin’s quest concerns the power that images have in influencing the masses and how the idea of national art itself can be questioned through art. His “mythological” figures are there to reveal the mechanisms that are at work when ideology uses images to control people. Despite their association to a certain national or racial entity, be it the Soviet or Jewish, they are not an educational tool subtly used by a certain ideology. They are about the rule of the game, not the game itself.

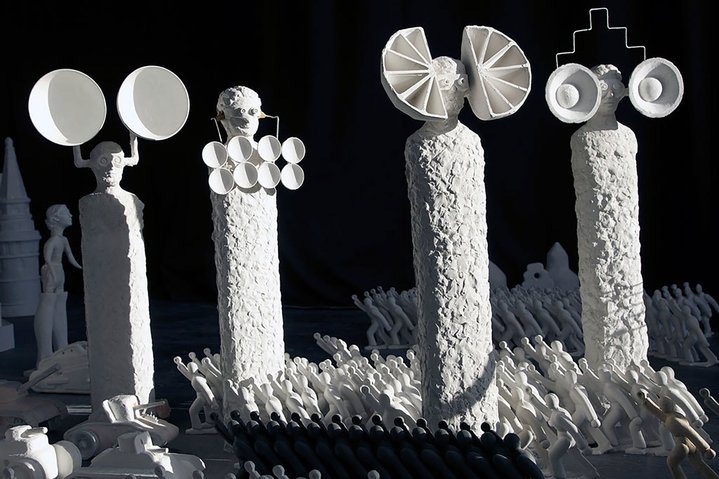

The ultimate task of the artist is that of fighting the temptation to build an aura around the subjects he depicts and presenting them as a narrative of power which deconstructs (and undermines) all narratives of power which control people’s lives. The artist thinks about the ways in which in the theatre of history decorations keep changing and it is the act of investigating this process, rather the decorations themselves, that motivates his work. Bruskin’s contribution to the Russian pavilion at the 2017 Venice Biennale, a total installation, aptly titled ‘Change of Scene’ is a pertinent example that illustrates the artist’s “signature” work. These were figures of anonymous people frozen in action on monotone backgrounds (or uniform material), which enable us to discern the archaic under the coat of the contemporary. But, are these people heroes or villains?

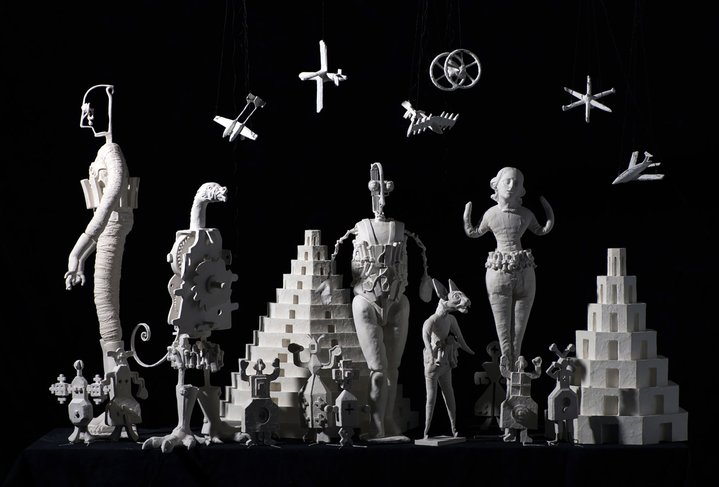

This hero/villain duality often lies at the core of Bruskin’s investigations into the making of myth. His series of sculptures title ‘H-Hour’ (2011), for example, scrutinizes the figure of an villain — of any villain: for instance, a hostile country, an enemy of the people, an enemy who lingers in our subconscious or even the ultimate villain, death. The starting point for this series, as for all his art, is the artist’s own life. When he was a child, all public spaces were covered with Soviet posters warning about the dangers of an attack from the enemy and invited Soviet citizens to get ready for when the attack might actually happen, when the “H-Hour” would come. Such a series harmoniously rhymes with his series of sculptures titled ‘Birth of a Hero’ made in 1984--1985, which depicts heroes from Soviet and Jewish mythology.

The plethora of subjects selected by the artist relating to a particular mythology makes the work of the artist similar to that of an entomologist collecting and studying insects. One difference is, however, that, here, the artist is consciously making art, as if writing a letter to the people of the future. Artists can not change the political, economic and social structure of the present. For example, as Bruskin recalled, during Soviet times, nobody had any idea when the current political system was going to end, if it would ever end. Therefore, when making a work, artists must not worry about the present and imagine an archeologist living in the distant future, who one day will find their work to help him piece together a real picture of the past. Most important of all, the artist’s work itself must bypass whatever ideology is in power at a particular moment of time. Further, in the future, Bruskin’s ‘Fundamental Lexicon’ and a work of art belonging to the canon of Socialist Realism made the same year should be studied together to understand that the former is much closer to the truth about the way people lived at the time when both works were made. It follows that the artist should be able to transcend time keeping in mind that a work of art is a precious testimony of its own time and has an inestimable value for archeologists of the future.

Clearly, though, what counts most of all is being true to oneself. Bruskin’s art has proved through the years that the success of a work does not depend on breaking records at auction. It depends instead on that very intimate moment when the artist is in front of his work and suddenly realizes that the message in the letter to the archeologist of the future is clear.