Granova wrestles with the Soviet past

Portrait of Katya Granova. Photo by Oleg Korzun. Courtesy of the artist

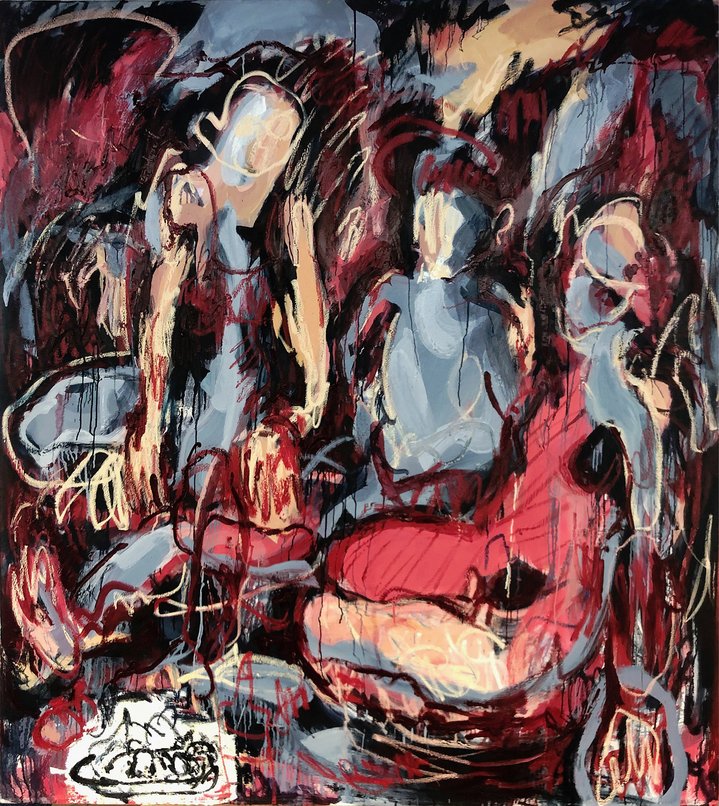

An artist with both Russian and Ukrainian roots is trying to process her family’s troubled past in a series of paintings based on photographs. Her solo exhibition called Voices from a Suitcase is now on view at Shtager&Shch gallery in London.

Katya Granova (b. 1988) is on a personal mission: to grasp the elusive nature of the past and bring to life Soviet history by interpretating and reconnecting with it in the present. Looking back at pre-revolutionary Russia or more recently the Soviet 1970s and 1990s, the artist bridges the personal and the collective using photographs drawn from her family archives or photographs she has found.

As a millennial, Granova grew up in the immediate aftermath of the USSR. She came of age as ideologies of the Soviet Union with its old certainties and understanding of history crumbled, and this led the artist to reflect on how ambiguous history is, with its many faces. She finds especially interesting the contradictory narratives of the Soviet past many of which have not been addressed, moments of nostalgia blended with seething resentments; there is often a sense of collective amnesia. “My family, like many others had conflicting ideas about the Soviet era. My parents were young in the 1980s and they loathed it, but my grandmother revered the communist times,” says the artist. Her goal is not to fix the past but to draw attention to its complex nature reflected in the historical experiences of the ordinary people. Vintage photographs became a starting point for the creation of an expressive body of paintings. “I began working with photographs of my family, and then I used found ones, as they give me more creative freedom to invent a story around them. But I do like working with my family pictures because I feel more emotional about them,” says the artist.

In Granova’s works, merging into the background, there is often a line-up of ghostly figures. It is as if she is grasping at a preservation of those who are no longer there, such as her own grandparents or even strangers depicted in photographs which she finds in flea markets. There is a sense she is balancing the great irreconcilables: love and loss, presence and absence, life and death, togetherness and separation. Her paintings also reflect a search for a sense of belonging.

When Granova moved to England six years ago, she began to question her own sense of identity, rethinking her dual Ukrainian and Russian heritage. In her new homeland, Granova suddenly felt an acute sense of her own past as being unresolved, she refers to it as blurry, out of focus both on a collective and personal level. It led to feelings of isolation and alienation and self doubt about her own origins. “I felt a compulsion to engage and interact with the past to address and move past the alienation I felt as an immigrant. So, I started by working with old photographs of my grandparents which I expanded into a large scale” explains the artist. “I wanted to interact with them on a physical level, so I painted over them. It brought energy to my brush, it was as if my unsolved past was in some way fuelling my brushwork and thus enabling me to reach a new level of passion and expressivity in my painting,” she adds. The brushwork in her large-scale paintings evoke Cecily Brown, with the monumentality of Rubens.

For Granova’s most recent solo show, Voices from a Suitcase, which has just opened in Shtager&Shch in London, she chose ten works she had painted during the past five years. The suitcase is a metaphor for the collective experience of immigrants. “They do not just bring novel cuisines or foreign languages, they carry with them their national past and identity. I come from Russia, it’s a country with a complicated history that has not been fully worked through,” she explains. “Almost every family in the Soviet Union confronted some tyranny, whether it was war, trauma caused by the KGB, imprisonment, or as was the case in my own family, murder during the revolution. I have this history still weighing me down in my suitcase and I have to address it as I start my new life. My painting practice is a way I have of dealing with that,”.

The exhibition opens with ‘Navy Sailors Sunbathing’ a painting based on a photograph from the 1970s of a group of young sailors enjoying the sun at the seaside in Sevastopol. Crimea was the artist’s second home, a place she spent the summer with her grandmother. She explains: “This image is ambiguous. The young men seem very human and laid back while they relax in the sun, there is no immediate sense that they are in there on military training.”

Her painting ‘New Year’s Kindergarten Party, 1970’ refers to a new year celebration in 1970, the herald of a new decade, in a nursery school in Simferopol, Crimea. It depicts Granova’s mother surrounded by children all dancing around the Christmas tree. There is a photographic image underneath, peeking out, capturing a familiar scene in standard Soviet photo albums. In ‘Pediatric Surgery’ which shows surgeons operating on a child, the figures are almost abstract as they merge with the background. The work was inspired by a photograph taken in the 1960s of her grandfather who was leading a medical operation. “My grandfather passed away not long after I painted it. I was exploring the dual reality of his absence in life and presence in the photograph. Roland Barthes' understanding of a photograph as a documented dead moment was particularly relevant for me here.”

Granova does not reveal the original images or narratives at the exhibition where viewers are left to make their own interpretations. Perhaps she sees in this the chance to turn the narrative into a new story. And biographical connections and the artist’s rather pessimistic view of the past do not easily sit in harmony with the rose-coloured paintings on display. That Granova prefers not to explicitly reveal the connections between her narrative and the images, perhaps gives her a sense of freedom to confront the past.