Gabriel Prokofiev’s Totality of Sound

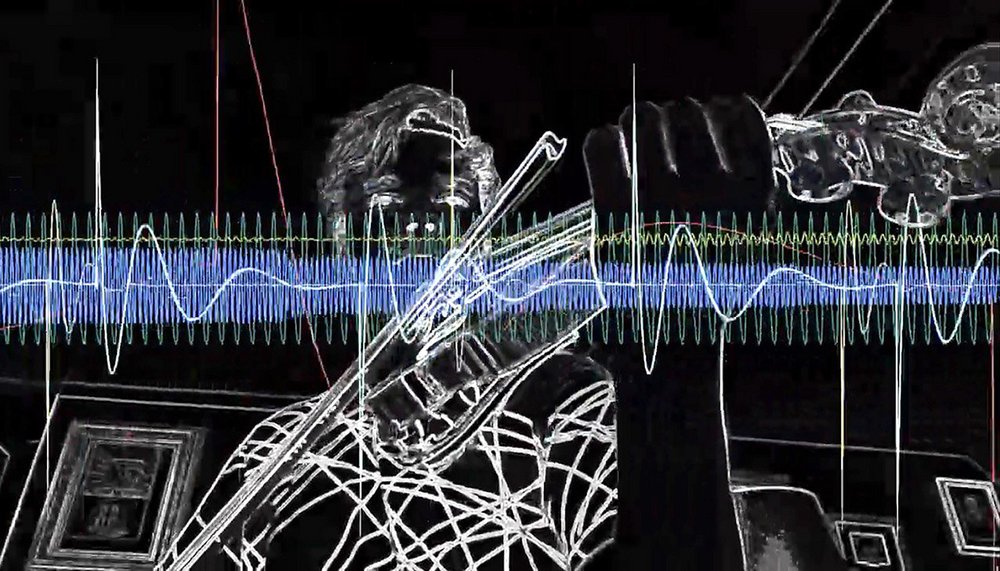

Gabriel Prokofiev, Yuri Revich. HOWL! - II - 'Separation'. Courtesy of the artist

Gabriel Prokofiev’s work encapsulates an idiosyncratic blend of tradition and experimentalism which pushes the boundaries in contemporary music. His compositions, rich in eclectic soundscapes resonate with today’s diverse musical landscape.

Arising from a struggle to overcome the limitations of traditional techniques, you often need to listen to works by contemporary composers several times to be able to grasp something of the initial idea at the heart of their radical experimentation. If you do not like it, you can listen to it again, and again. The perceptual and intellectual hurdles that today’s classical music presents to listeners are now seen as its essential aesthetic feature. And at a symbolic and metaphysical level, it mirrors the discordant dynamics of our contemporary societies.

“I was once invited by Joby Burgess, one of the greatest British percussionists, to write a solo work for him,” composer Gabriel Prokofiev (b. 1975) tells me in his new studio overlooking Regent’s Canal on a rainy autumn morning. “There is a famous piece by Xenakis called ‘Rebonds’, energized, exciting music featuring tom-toms, a bass drum, and a gong. I thought I would do something similar. Later, in a corner of Burgess’s studio, I noticed a Fanta bottle that has ridges on it, so you could rub it like a guiro. It felt sentimental, because I’d lived in Tanzania for nine months, and they had the same ones there. That’s how my piece for the Fanta bottle came into being.” During the performance, Burgess blew up a plastic bag, tapped it, and made some intriguing bass sounds. Other movements incorporated a wooden pallet and an oil drum—very strange junk objects that transformed the entire work, titled ‘Import/Export’, into a representation of globalization.

Gabriel Prokofiev who turns fifty next year represents a new generation of composers, working across a wide range of genres: chamber music, concertos for soloist and orchestra, operas, ballets, electroacoustic experiments, and film scores. His gravitation towards the classical tradition is rooted in an eclectic fascination with EDM in the ‘90s and his involvement in various pop music projects. The last of these, the disco-funk-house band Spektrum, distinguished itself in the early 2000s British scene with its extroverted nature, syncopated grooves, vocal modulations, and unconventional programming. While these qualities set Spektrum apart, they may have hindered its success in the mainstream. Nevertheless, ‘Enter The Spektrum‘, the band’s debut album, still sounds fresh two decades on. “In the world of pop music, you face so many pressures from the industry,” Prokofiev reflects, gesturing expressively. “Everything follows trends as closely as possible, which can be very narrow in creative terms. It’s ironic, since pop music was initially seen as rebellious, but now it’s very conventional most of the time.”

2003 marked Prokofiev’s transition to classical composition with his first string quartet. Built upon a foundation of familiar rhythmic, quasi-dance structures and fluid melodies, the piece created harmonic tensions that, while obscuring clarity, effectively conveyed an inner drama. This work also became the cornerstone for Nonclassical, Prokofiev’s label dedicated to curating monthly classical music events in unconventional settings and releasing music by fellow contemporary composers. “Now we are hosting our biggest event ever with the London Symphony Orchestra at the Hackney Empire. There will be thirteen composers and all the compositions are new. The LSO is considered as one of the best orchestras in the world, and it is a great coup that they are performing for Nonclassical. That is a big sign of what we have achieved over the past twenty years.”

Prokofiev gained true recognition with his Concerto for Turntables and Orchestra (2006)— a work where the DJ manipulates sounds produced by the orchestra itself. This composition caught the attention of ensembles worldwide, including the National Youth Orchestra, which performed it alongside world scratch champion DJ Switch (Anthony Culverwell) at the BBC Proms in 2011.

In a subsequent concerto, Prokofiev elevated the bass drum to a solo role. This instrument, while crucial in EDM, is relegated to a utilitarian, fragmentary function in orchestras, primarily used for dramatic emphasis. Collaborating with Joby Burgess, Prokofiev expanded the bass drum’s sonic palette through various techniques: rim tapping, striking metal lugs, chain dampening and coaxing whale-like sounds by rubbing the drum skin. This exploration echoes the influence of Jonty Harrison (b.1952), Prokofiev’s professor of electroacoustic composition at the University of Birmingham. Harrison’s work explores the structure of individual sounds, exemplified by his 1982 piece Clang, which is built from the metallic clatters of a Le Creuset casserole dish, enriched by harmonizer modulations, frequency filters, and cassette recorder manipulations. “I had terrible, but then afterwards maybe positive feedback when my bass drum Concerto premiered at The Roundhouse in Camden,” Prokofiev recalls. “I was very nervous, as it was my second piece with a symphonic orchestra. During the concert it felt great; the audience was swaying to the music. Just before the final applause, someone shouted, ‘Rubbish!’ It felt like a knife suddenly stabbing. We rarely get such strong reactions: at most contemporary concerts, people are very polite. Yet, it’s good to be hated sometimes.”

Gabriel was born in Southeast London to artists Oleg Prokofiev (1928-1998) and Frances Child. Oleg, the second son of the renowned Russian composer Sergei Prokofiev (1891-1953), studied under Robert Falk (1886-1958) and took part in underground exhibitions in Moscow during the ‘50s and ’60s. He married British art historian Camilla Gray, a researcher on Russian avant-garde art. After Gray’s sudden death in 1971, Oleg Prokofiev was granted permission to leave the Soviet Union with their daughter Anastasia and settle in England. There, he was awarded a fellowship in the Fine Arts Department at Leeds University and later met Child.

Gabriel’s creative reflections consistently underscore the profound impact of his artistically charged upbringing. The shadow of his grandfather—whom Prokofiev often cites as a personal influence and the last great melodist of the 20th century—looms large over his work. “People always suggest that I create a remix of ‘Peter and the Wolf.’ But to play with it, after I’ve spent a long time building my own voice, identity, and career, would feel very much like a marketing trick. I’m already so close to my grandfather’s music.” Whether due to his heredity or not, Prokofiev forges deeply intuitive relationships with sound, prioritizing its emotional resonance. While various musical genres can generate emotional responses, Prokofiev posits that classical music possesses a unique capacity to unlock deeper sensory perspectives: “Again, music and emotions are closely tied. You can say you’re not interested in emotion, but you can’t deny that when people listen to music emotions will arise.”

Prokofiev’s first major opera, Elizabetta, commissioned by the Regensburg Theater in 2019, further cemented his position as a cultural phenomenon. With a libretto by David Pountney, the work draws inspiration from the 18th-century legend of the ‘Bloody Countess’ Elizabeth Báthory, infusing it with a healthy dose of irony that comments on the fear of aging and modern society’s obsessions with beauty. A significant part of Elizabetta takes place in a sauna, a BDSM club, and a TV studio. Musically, it is a stylistic kaleidoscope where elements of hip-hop, commercial jingles, musicals, techno motifscoalesce with traditional operatic arias and recitatives.

Early in 2024 saw the premiere of the ballet The Obstruction of Lightness of Thought at the Thuringia Bach Festival. Here, Prokofiev again employed his ‘genre-fluid’ compositional approach, blending old and new. The score combines Bach’s harmonies with electroacoustic fugues and textures created by recording the turning of pages from Bach scores. “This ballet includes solo piano music inspired by Bach, whose compositions allow the mind to turn and feel like it is accessing the wheels of the brain,” Prokofiev explains. “The choreographer I worked with, Andris Plucis, said, ‘Let’s enjoy moments where you can have light, wandering thoughts.’ At the same time, there are more turbulent orchestral sections that reflect the pressures we receive from our online lives. I was worried that some people might say, ‘Oh no, Gabriel, he’s gone soft, he’s turned classical.’”

Yet, he has most definitely not. Prokofiev is set to embark on a project fifteen years in the making: a Concerto for Synthesizer and Orchestra. For this, he intends to use the first mass-produced analog synthesizer, the Minimoog, whose distinctive sound has long been a staple across diverse musical styles, from funk to techno. “No one has written a concerto for synthesiser with a full symphonic orchestra,’ he says. ‘The piece will delve into an exploration of contemporary life: with an orchestra, you can create the landscapes, the people, the community, while the synthesiser is going to represent contemporary electronic living.”

“Music is the source of my energy, a moment of electricity,” Prokofiev often says, and this energy channels back into the world through his creative endeavours. One part of his artistic DNA is composed from strands from his grandfather, Schnittke, Varése, Bach, while the other draws from hip-hop artists, Fred Again, David Lang, Matthew Herbert, and other contemporary artists—a complete list of which he had promised to email me but never did. As for genres, there is no such divisioncontemporary or classical music. A contemporary composer must be able to encompass the totality of sound.