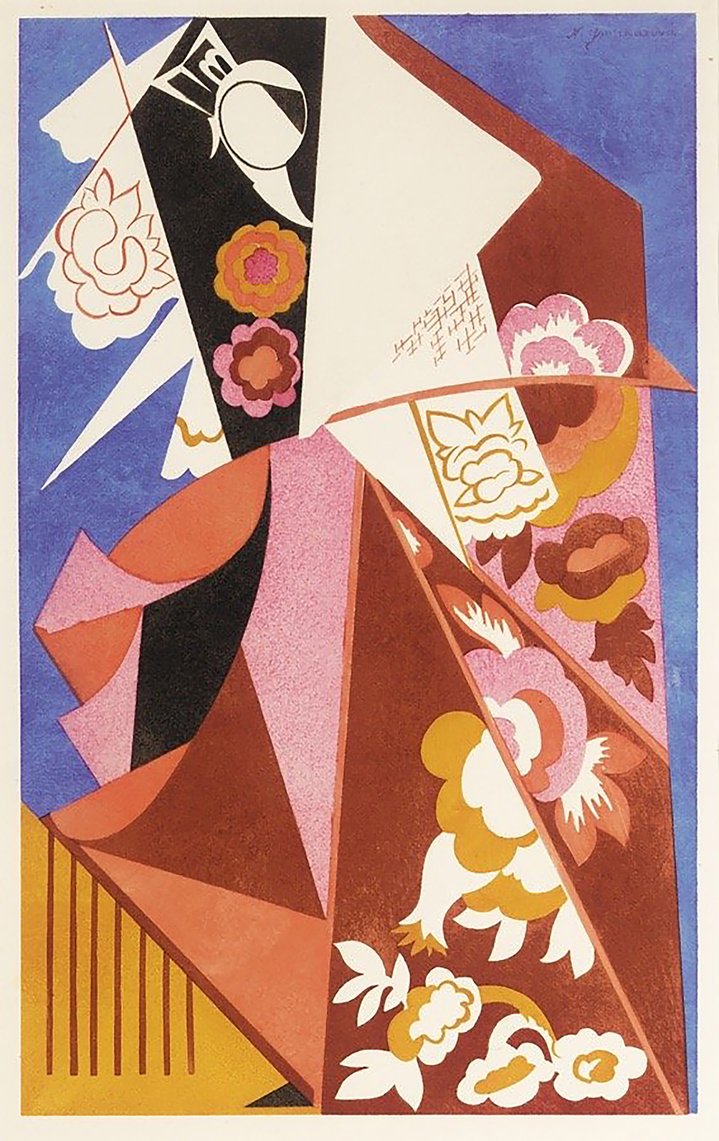

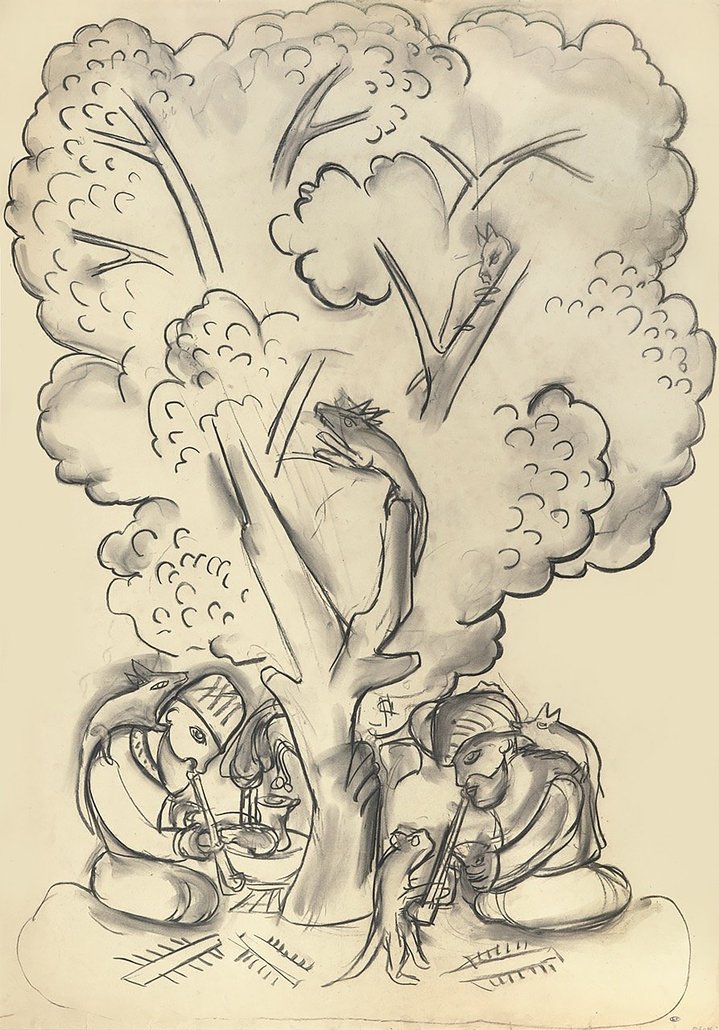

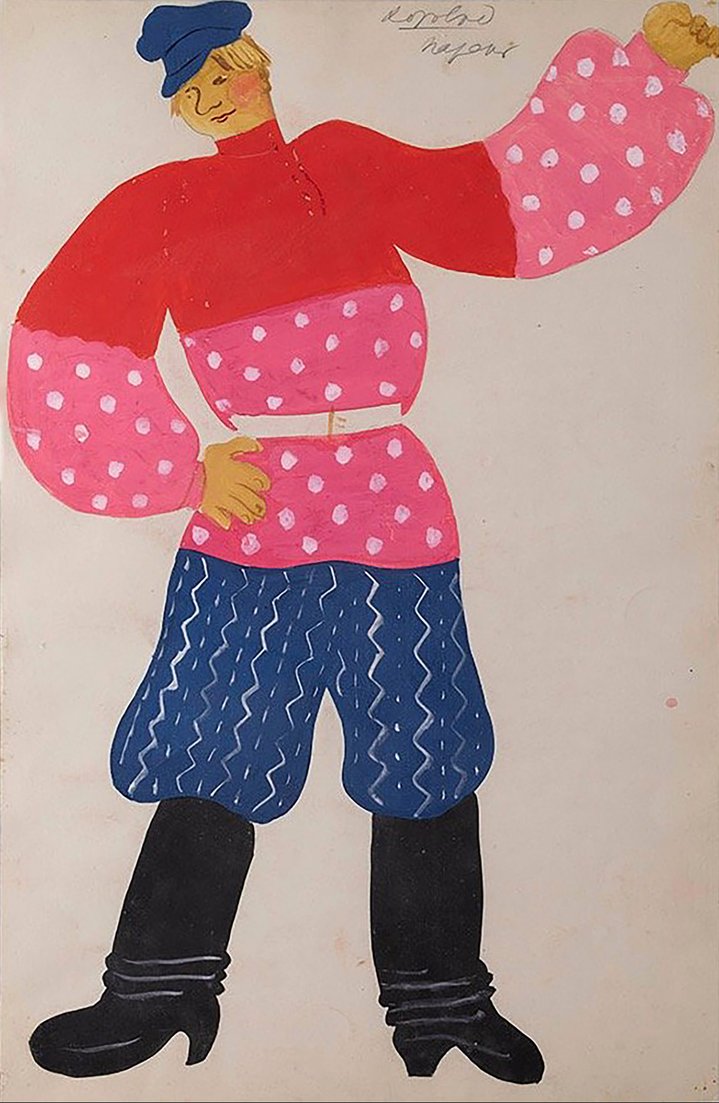

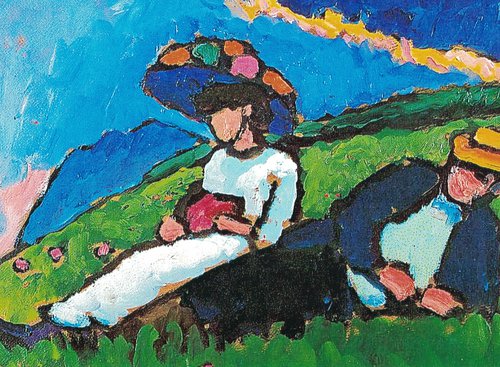

Mikhail Larionov. Set Design for Midnight Sun, 1915. Paper, watercolour, gouache, pencil. Courtesy of Jenny Dugan-Chapman Green collection

From Lowry to Larionov: the Story of Jenny Green’s Collection of Art

An exceptional private collection of Russian art assembled over two decades by London based art collector and 1960s fashion entrepreneur Jenny Dugan-Chapman Green is on public view for the first time at the Russian Museum in Malaga.

London-born with Polish roots, Jenny Dugan-Chapman Green is no typical collector of Russian art. Her natural taste for colour and flamboyance reflected in her art collection, initially found its expression in fashion. In the late 1960s Green grew up in the middle of a style revolution, spending all her days on the Kings Road, an iconic street in Chelsea which defined 1960s Swinging London. Her boyfriend then was Czech born fashion entrepreneur, Freddie Hornik, and together they set the fashion world alight with stylish shops called Mr Freedom, which sold beaded suits and jackets with fancy embroidery to budding rock stars. Then she worked for the famous clothes store called ‘Granny Takes a Trip’ which was so successful that Jenny opened a branch in LA, becoming the first to promote Vivienne Westwood’s designs in 1972. There is a wonderful photo of Jenny Green in her 20s in a Mondrian style dress, fashion and art, hand in glove.

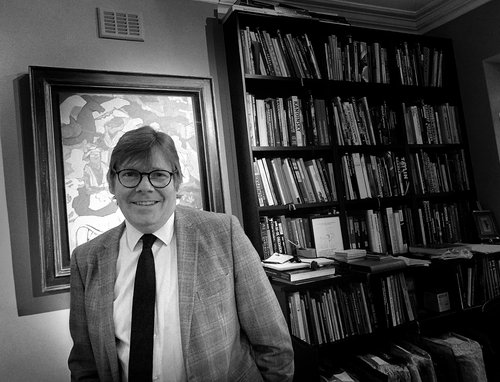

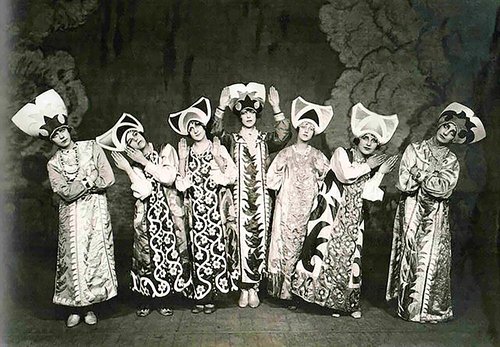

One fortuitous encounter in those years led to a close and long-lasting friendship which gave her an entrée into what was then the closed world of Russian Art. She met an Eton-educated, brilliant Scotsman called John Stuart, who had a love of the British Biker rocker movement, as well as Russian Imperial history and icons. Johnny, as he was known, had converted to Russian Orthodoxy when he was 18 and later went on to establish the Russian art department at Sotheby’s in 1976. Green had met Johnny “somewhere on the King’s Road” as she puts it today. It was Natalia Goncharova’s art she first became aware of, in particular a portrait of the poet Nikolai Gumilev which she vividly remembers hanging in Johnny’s house. And later Goncharova’s bright and exotic theatre designs all of which sparked off her own interest in Russian art. It was with Johnny that she visited Russia for the first time in 1970

When many years later, Jenny Green began to collect Russian art herself, she already had some personal experience in art collecting by proxy, through both her father-in-law, who loved Modern British art and had an impressive collection of paintings by L.S. Lowry, and her Polish born father Charles Dugan-Chapman (born Ignacy Czajka). He had been a champion fighter pilot in the second world war, yet extraordinarily, at the age of seventy he had decided to embark upon a new career as an art dealer. At a pace, he acquired Pissarro’s, Munch’s, among works by countless other masters of European Modernism, before tragically he began to suffer from dementia and the art collection stalled and was eventually sold off by Green and her sister at Sotheby’s in the early 2000s. However, even before then, they had started to make changes to the family collection, by way of acquisitions and sales. The additions were mainly works by modern British artists but at some point, Green turned to Russian art.

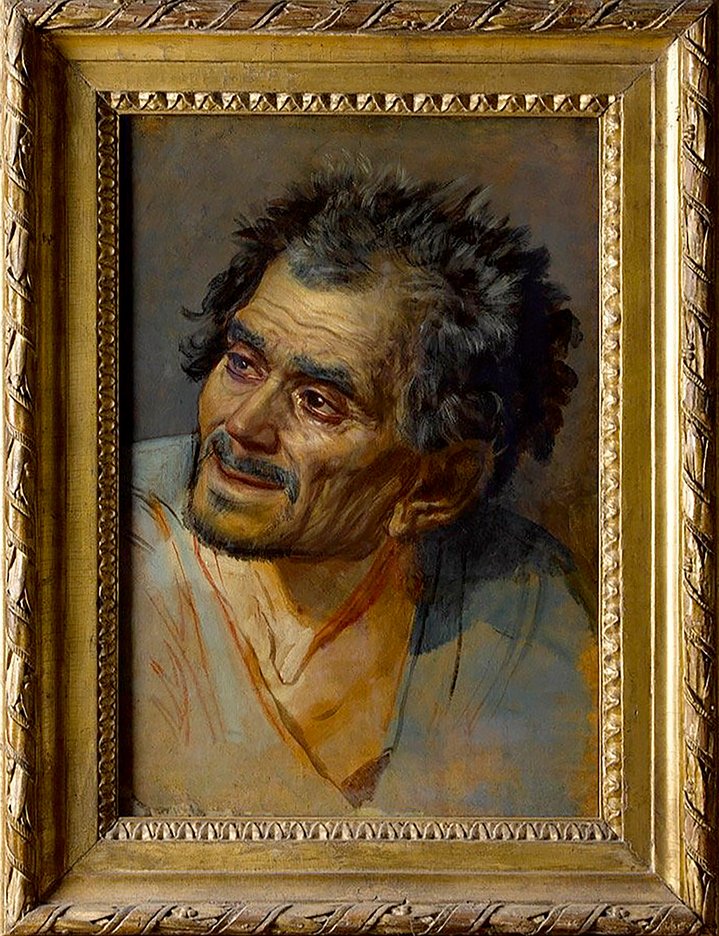

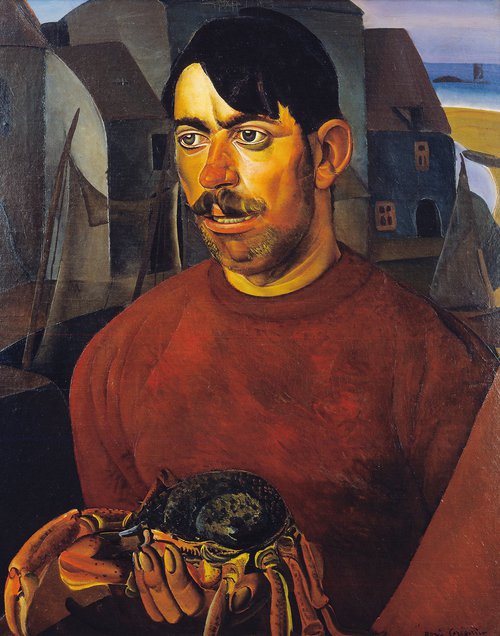

The first Russian painting she bought was in 2004, the ‘Praying Boyar’ by Dmitry Stelletsky (1875–1947) which she acquired at Christie’s, chosen because “Johnny would have liked it” she admits. She had already started to have discussions with Johnny about collecting Russian art not long before he died. With the Boyar, it seems she had been putting her toe in the water: their tastes were different. Johnny had been most interested in Russian icons and Imperial Art. In Jenny the fin-de-siecle dandyism of the vintage fashion movement met with the Russian world of art movement and the exoticism of the ballets russes theatre designs. Over several years, her taste began to assert itself in what has today grown into a homogenous collection of mainly modern, figurative Russian art characterised in part by colour, pattern and — what is evident when seeing the works hanging together - a joie de vivre. Besides the bright colours and ornamentation, are characterful, expressive portraits, as well as a few hand-picked Russian old masters, such as an Alexander Ivanov (1806–1858) sketch for his magnum opus and even a little winter landscape by Ivan Aivazovsky (1817–1900) which exudes charm. She has been guided and helped since the beginning by Ivan Samarine, who worked with Johnny at Sotheby’s and with whom he started a Russian Art advisory in London in the late 1990s. Ivan is behind the current exhibition at the Russian Museum in Malaga.

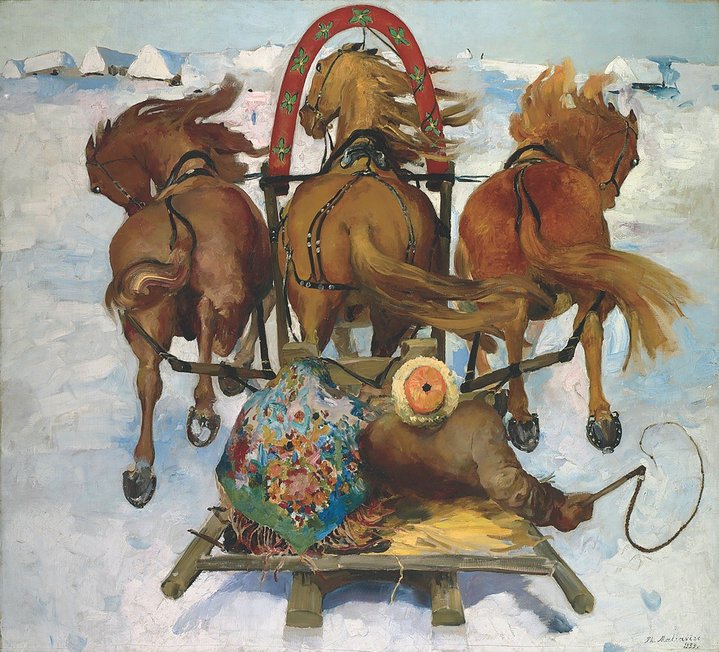

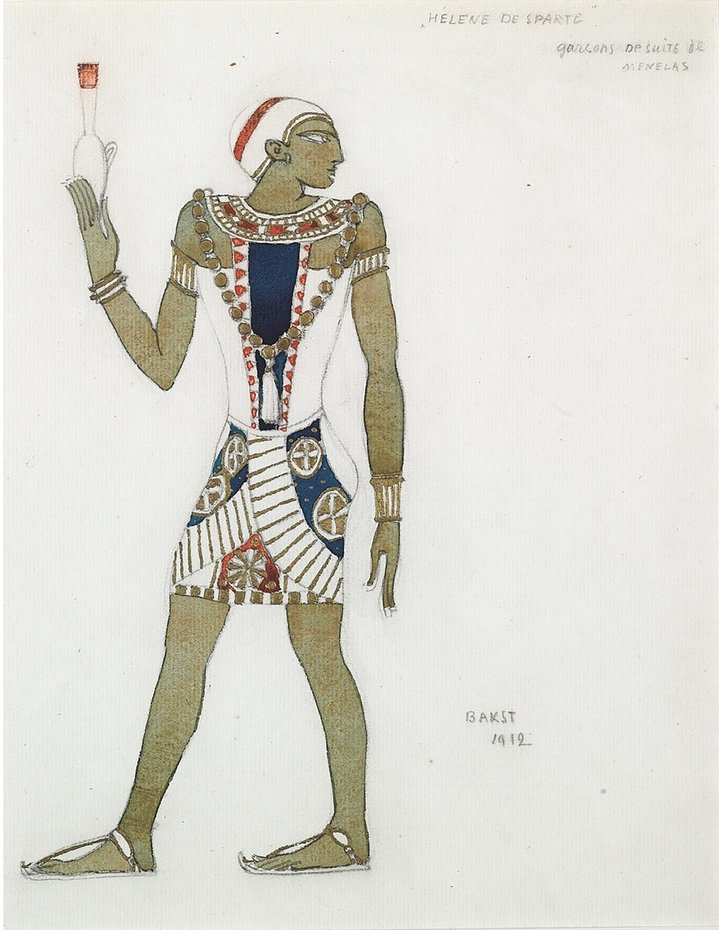

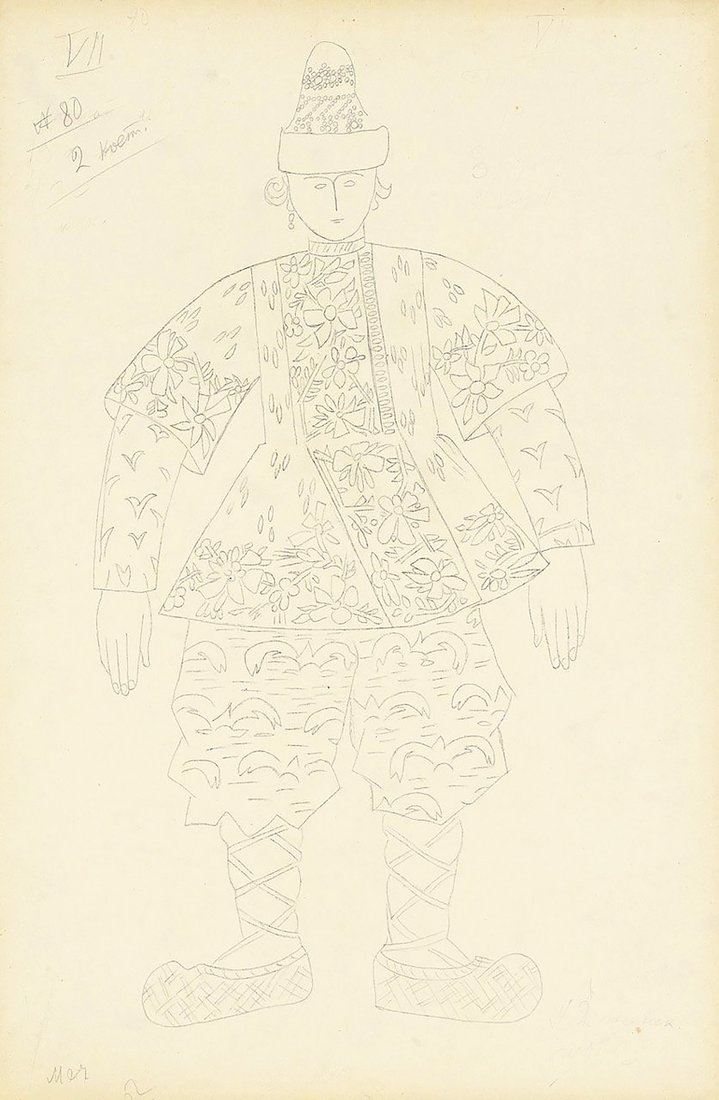

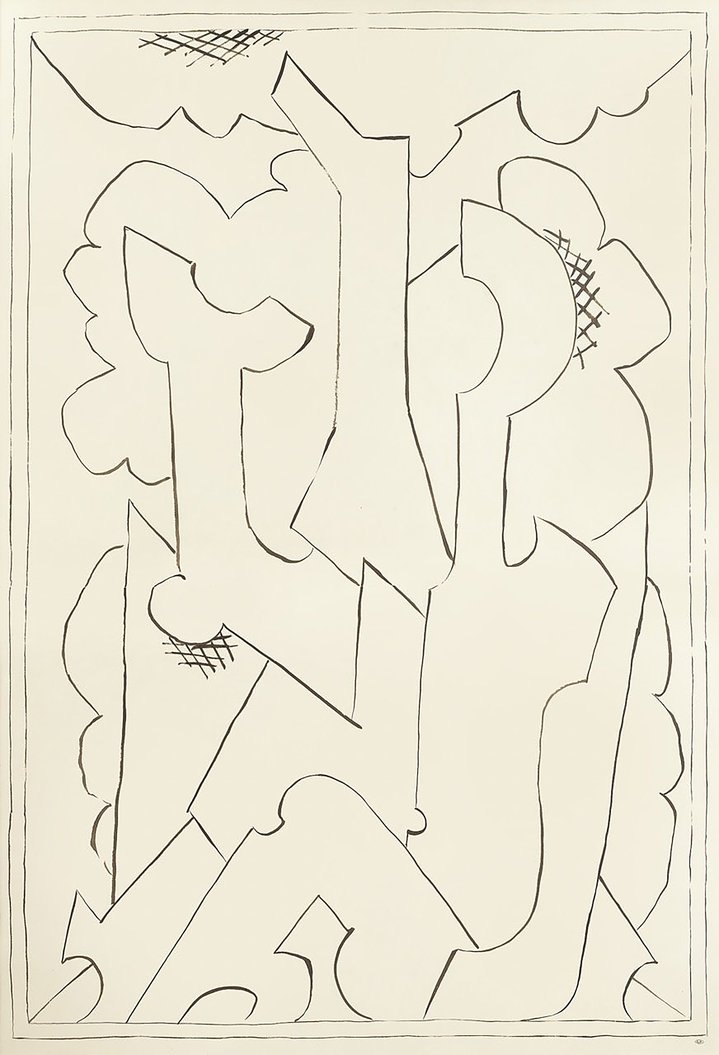

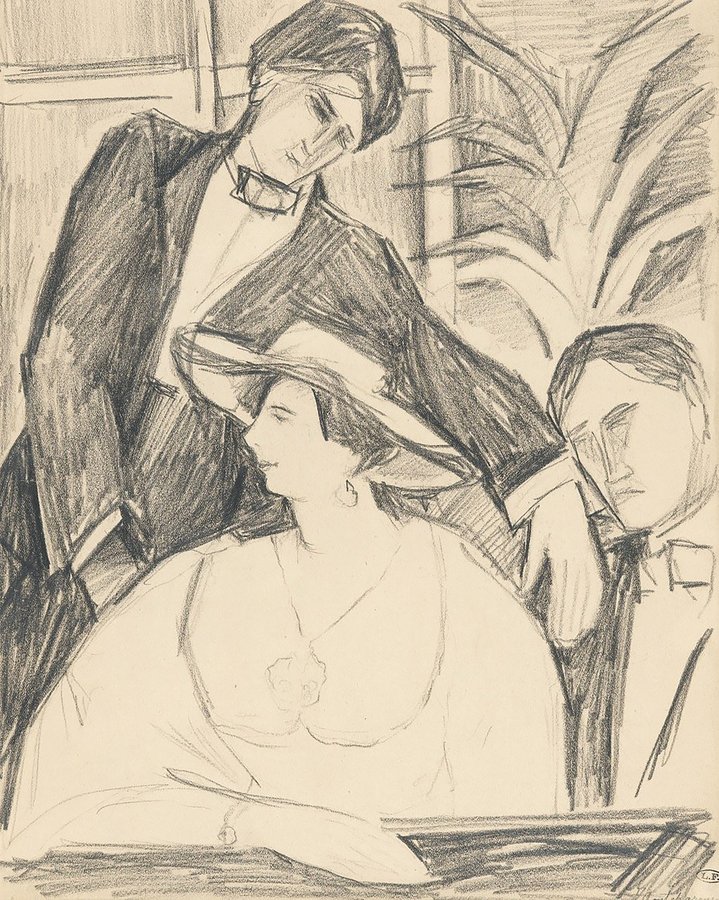

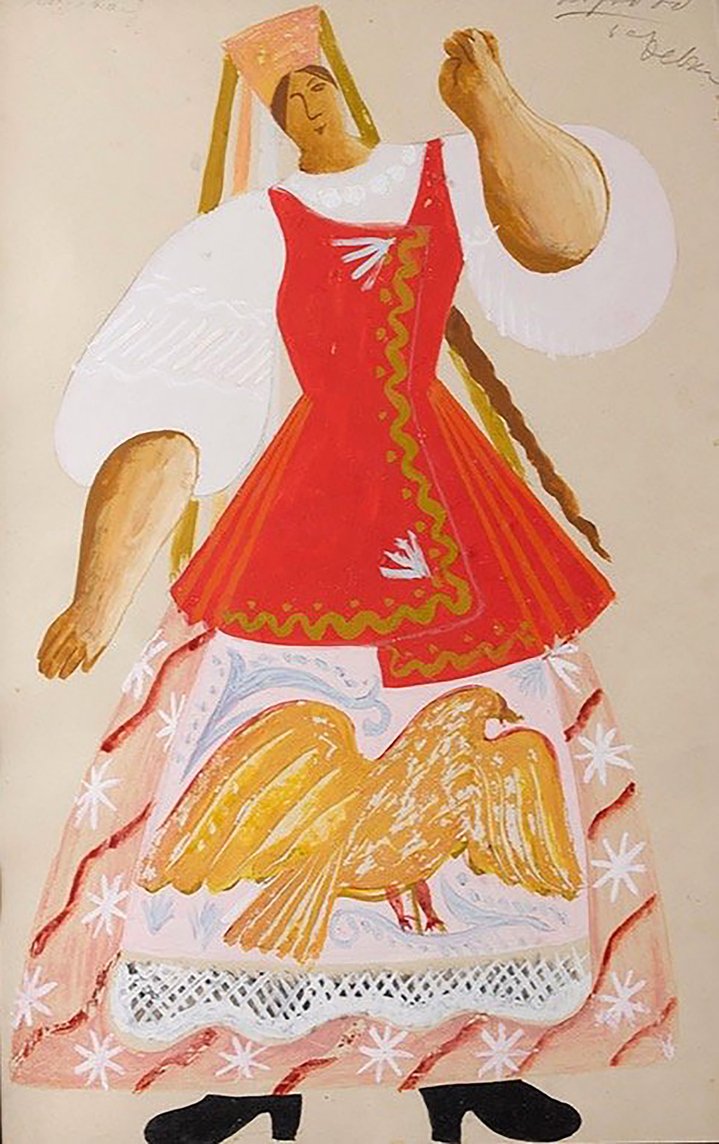

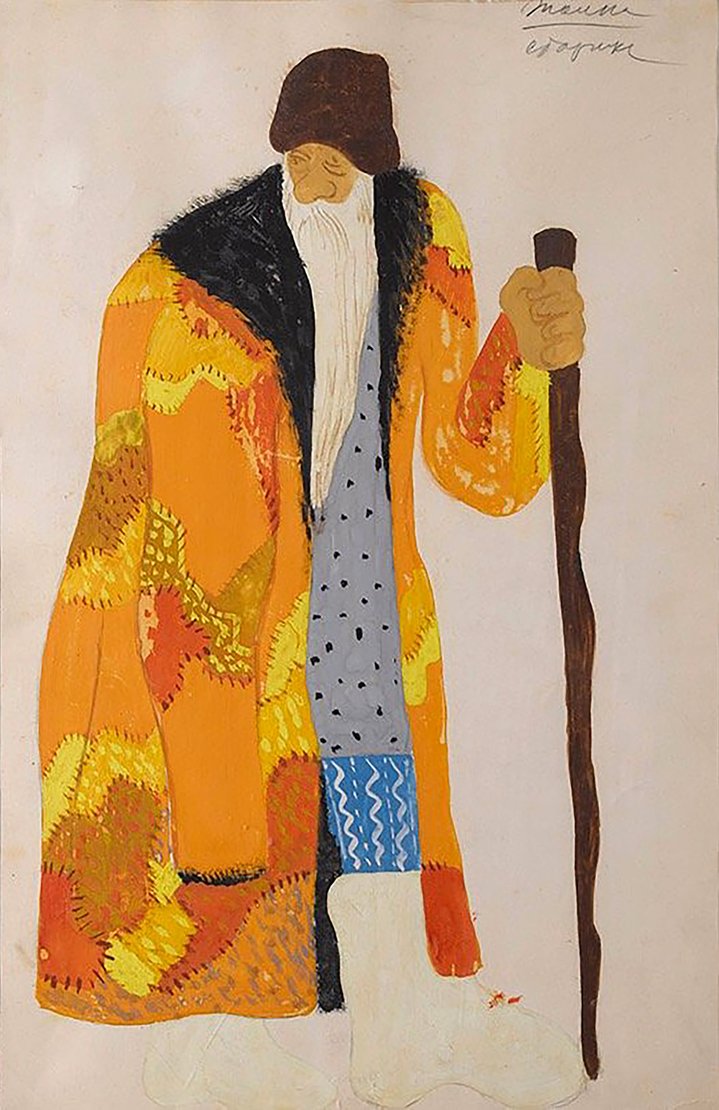

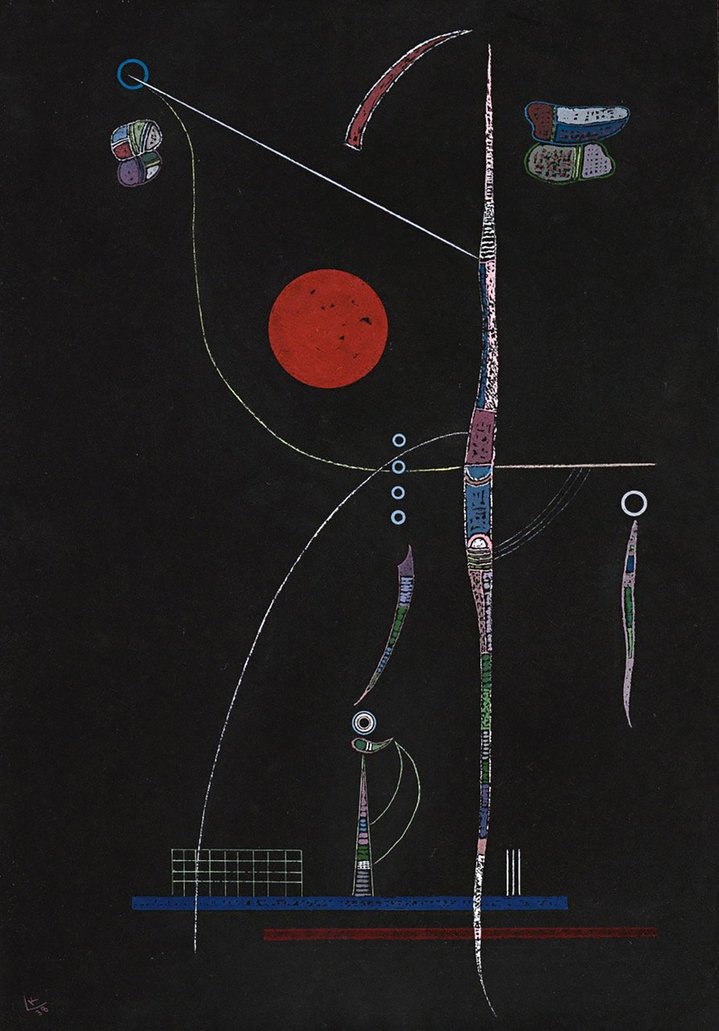

Although Russian art has turned out to be her second great love in life, fashion somehow weaves its way through the collection at every turn. There are striking ‘psychedelic’ costume designs by Pavel Tchelitchev (1898–1957) which might not have looked out of place once on the King’s Road; exotic designs by Lev Bakst (1866–1924); several works by Dmitry Stelletsky, and theatrical works by Natalia Goncharova (1881–1962) and Mikhail Larionov (1881–1964). Green has a particular affection for the work of Filipp Malyavin (1896–1940). She is mesmerised by a huge Malyavin painting which was exhibited at the Royal Academy in London, the massive, red symphony called ‘Whirlwind’ of 1906 from the State Tretyakov Gallery. “That dress! I remember that dress! It’s hard to remember a painting, to feel as though it is just hanging there in front of you, but that painting - I cannot forget it”. Like true love, it crept up on her gradually over the years and now she admits she gave up her interest in Modern British somewhere along the line to focus exclusively on Russian art.

Jenny Green has acquired many of the works at auction. It is not only Russian art that she has come to treasure most of all, but as a collector she also finds the market itself a more engaging experience. Comparing the British and Russian art markets, she explains: “If you want to buy a work by Frank Auerbach, you can look in the auctions and maybe twenty or so paintings will come up for sale in any one year, and you can choose which one you like. But if you are looking for a good painting by a specific Russian artist, you might not find one for years! Suddenly one day, there it is, and you cannot miss that opportunity to buy it. When something comes up for sale you like and want, you have to take your chance”. The modern British market is relatively predictable, paintings sell according to size and style, and for specific aspects which collectors prize. With Russian art “you often have no idea how much something might sell for; it is extremely unpredictable. The market is constantly full of surprises”.

In terms of art appreciation, Green finds Russian 20th century art far more diverse than its British counterpart. There is that sense of restraint and containment of British modern art whereas Russian modern art is a feast of colour, and the “artists are so uniquely different” she says. Her spacious, ground floor apartment in London’s chic Notting Hill neighbourhood feels a bit like an artist’s studio. White walls, now with the nails where once the paintings were hanging, arts and crafts furniture, a painting on an easel. There are drapes, bright cushions, set against the white walls which presumably vie for attention with the colourful paintings which normally hang there. “I loathe the ubiquitous hotel style of interior design these days, where paintings are part of the background”. It is clear that Jenny’s collection lives and breathes in her bright home, it is all about them rather than the space itself. Anyway, there is little space left when they are hanging, literally from the floor to the ceiling and above the doors.

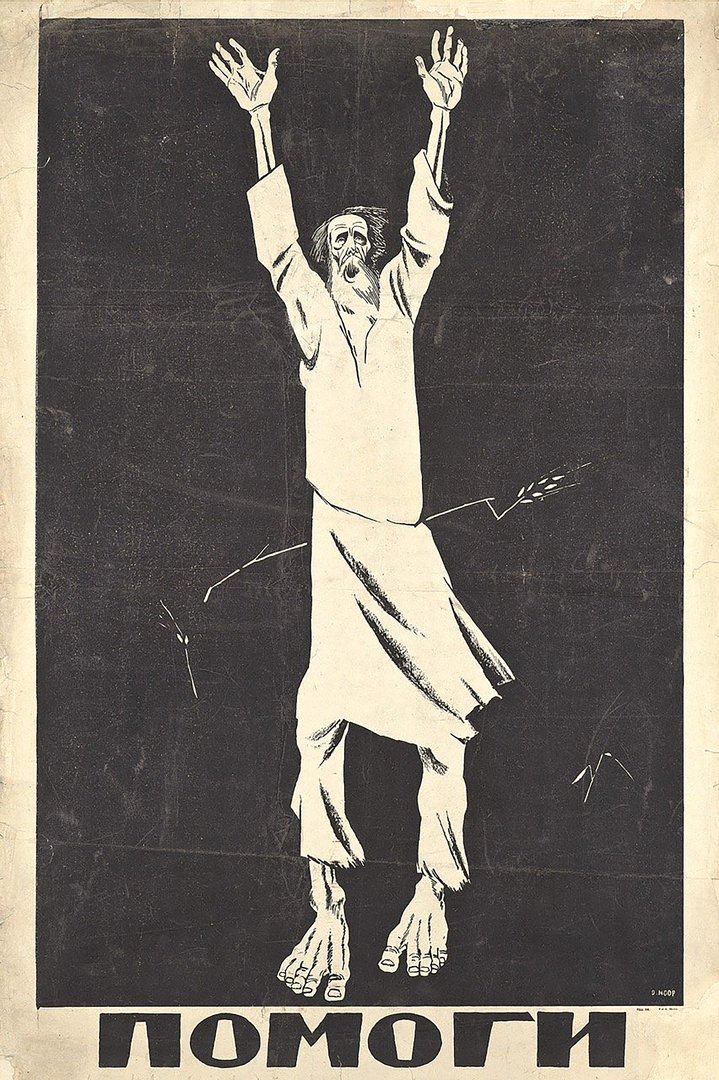

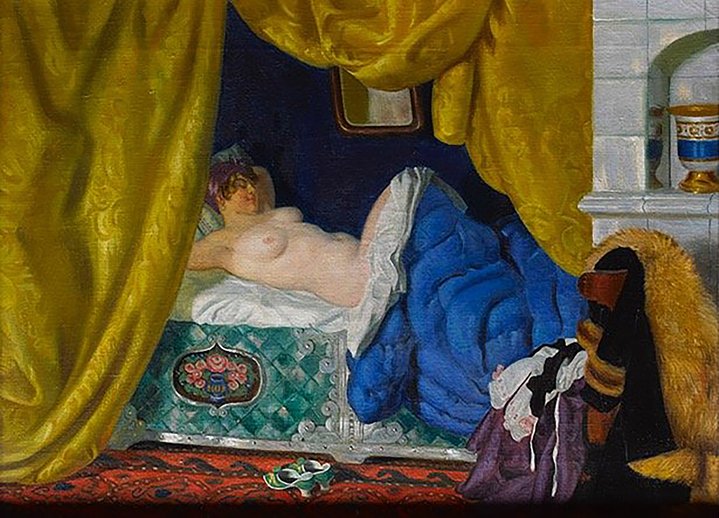

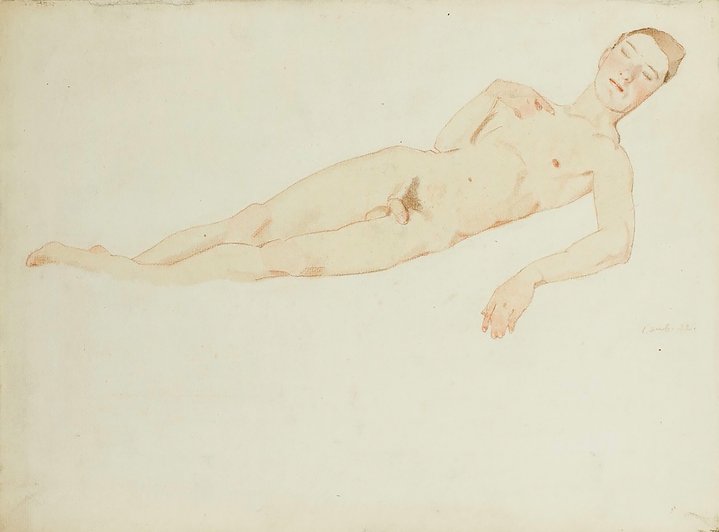

In life timing is everything, and when Green started out collecting Russian art in the mid 2000s, she found herself bidding side by side with the Russian oligarchs. Many Western collectors who had been buying in the 1990s were priced out and stopped taking part in the sales. Of the oligarchs, Jenny talks about buying “around them […] You had to choose something you hoped they wouldn’t like, otherwise it was impossible” she says with a confident smile. You get the impression she likes the chase, the hunt, and those opportunities where you find a truffle in the forest which no-one else has spotted. “There are things which many people don’t like, such as black and white drawings.” And one of the characteristics of Russian collectors she cites as her secret weapon: “they tend to be insecure buyers, if they do not think someone else is interested in a work of art, they will not buy it themselves”. Yet, to build the collection she often had to reroute, acquiring a different work in an auction to the one she had originally gone to bid on. She is also not shy of controversy: she bought the infamous Odalisque originally sold by Christie’s as a work by Boris Kustodiev, which was the subject of one of the most high-profile and costly court cases in London in the 2000s. Christies was forced to refund the buyer and ‘take the painting to house’, as it is called in the trade. Afterwards, as the result of a chance discussion, Ivan Samarine acquired the painting for Green for an undisclosed sum.

I ask her if she has ever thought about diversifying her collection, but she sees the field of Russian art as exceptionally broad and varied, “it’s not a limited palette” as she puts it. The collection is not finished, and the response she has had from the exhibition has now encouraged her to think about new acquisitions. The exhibition has been well received in Malaga, with visitors excited by what they describe as a positive and joyful experience. We hardly talk about the current political situation, however, when we do, Green mentions that in Malaga the locals talked freely and openly about how one must support Russian culture even at this time.

Jenny Green’s Russian art collection and exhibition is a celebration and culmination of her love and curiosity for another culture, honed with great personal taste; and I do think she has brought all of her personality to this task. The last room in the show reflects her own life story which in itself is fascinating. Green admits that in the UK it is not common to exhibit in public the art collection of a private individual. With a committee or board, you may have political correctness, but a more personal exhibition like Jenny Green’s collection show creates an experience which speaks directly on a human level without popular ideologies which themselves come and go. And although Russian art exhibited in the south of Spain from a private collection in London is an unlikely blockbuster, this may be the best exhibition of Russian art you will see outside Russia for some time to come.

Russian Art, an English View. A Private Collection of Russian Paintings

Malaga, Spain

December 13, 2022 – June 5, 2023