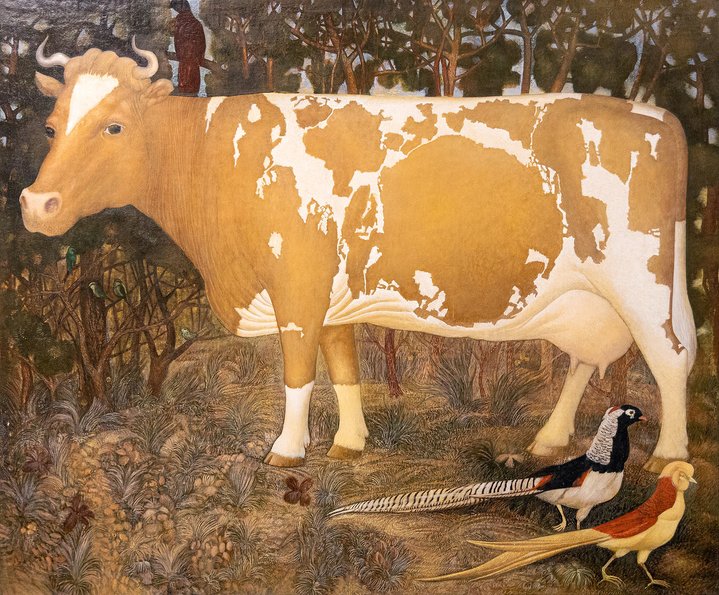

Igor Vishnya. Congress of Rabbis in France in the XIII century, 1994. ‘Chose the road — do not turn off!'. Yevgeny Roizman’s private collection. Courtesy of Boris Yeltsin Presidential Center. Photo by Lyubov Kabalinova

From Icons to Contemporary Art: the Collection of the Former Mayor of Ekaterinburg

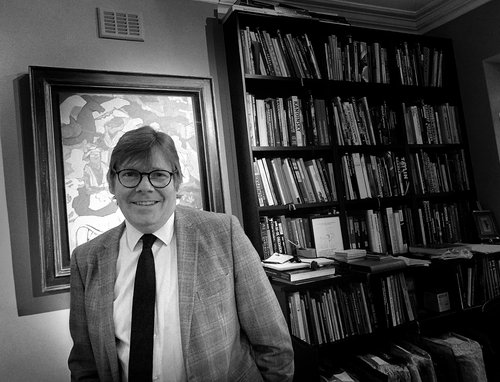

Declared a foreign agent by the Russian authorities, Yevgeny Roizman was the first collector of icons in post-Soviet Russia to open his own private museum in 1999. His other passion is collecting contemporary works by artists from the Urals.

The Nevyansk Icon Museum was the first privately owned museum in Ekaterinburg and one of the earliest museums to promote private art collecting in general, reflects Roizman. Back in the late 1990s the country had changed radically and he saw it was possible to collaborate with the new authorities, a view which has long since changed: "Although I did then [ed. see the possibilities of collaboration with the authorities], today I would not say so". That said, Yevgeny Roizman still believes in the transformative power of art. As he once said in an interview to a local magazine in Ekaterinburg: "Only culture can save this country. International relations can only be saved by culture, common culture and serious cultural projects. Culture cannot be anti-human and mean-spirited. It is a concentration of all the best qualities of humanity as a whole".

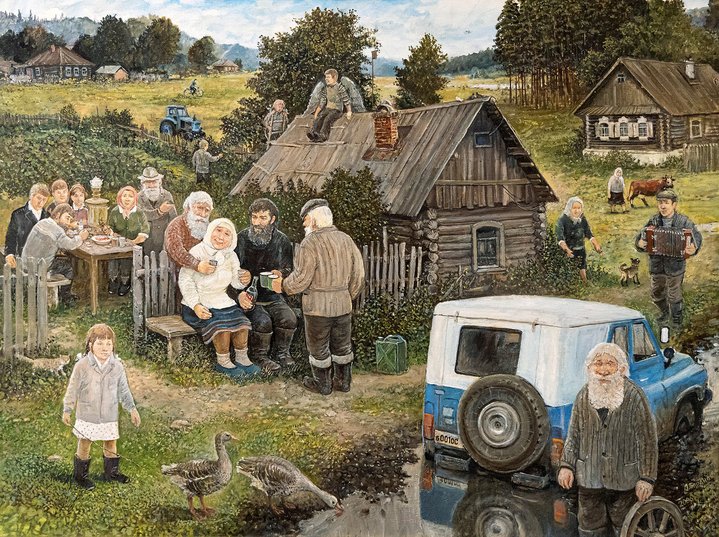

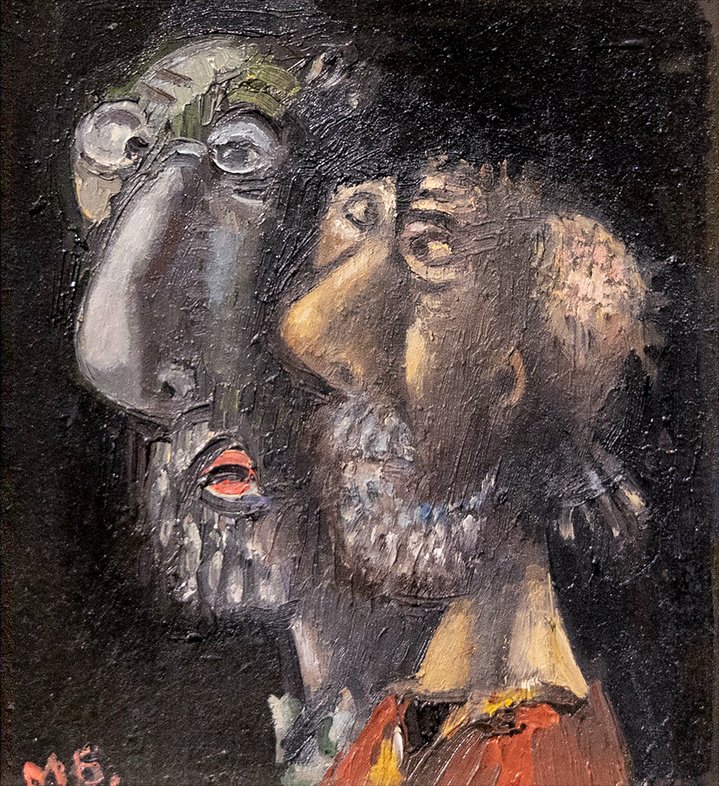

Yevgeny Roizman, a former mayor of Ekaterinburg, former businessman, former politician and public figure, was recently sentenced to a fine for making public statements condemning Russia's actions in Ukraine. His is a congenial presence, warmly meeting visitors in person in the exhibition hall of his museum. In the window on display there are prints of contemporary artworks from his collection. On the façade near the front door, naked nymphs fly and a hero in the guise of Hercules, strikingly similar to Roizman, rips open the jaws of a lion. The collector had planned to show the original work on which the print is based at an exhibition of his collection in the Yeltsin Centre in Ekaterinburg, a show which took place last winter. The broad retrospective survey of Urals art, from the 19th century to the present day, which he had conceived himself did not turn out quite as planned. The Roizman collection includes naive art (in 2012, the collector gave his museum of naive art to the city, and the private museum was incorporated into the Ekaterinburg Museum of Fine Arts), academism, nonconformist art, works by nonprofessional artists, and a large collection of works by Misha Brusilovsky (1931–2016); it spans at least six major movements. Despite this varied palette, everything is united by Roizman’s interest in Uralic art. Roizman calls it "overcoming the mishap of Mamin-Sibiryak," a 19th century writer from the region who, according to the collector, never made it into the literary pantheon of the first rank because he lived beyond the Urals.

The curators at the Yeltsin Centre made a strict selection, not quite what the collector himself would have chosen. "I have a museum of Ekaterinburg artists ready to go," says Yevgeny Roizman". 11,500 people came to the exhibition over a month and a half. We showed three hundred works, after they had cut out another two hundred and fifty!" Roizman thinks young curators lack necessary experience and have a very “different idea of what is beautiful and good".

While talking about the history behind his collections, Roizman recounts the history of his city and the Urals, and the local artistic milieu. "Ekaterinburg is a very complicated city, it is very different from other Russian cities," says the collector, "It was conceived as a major European factory town and until the end of the 18th century, German was used as the language of business".

Discussing Urals identity, Roizman, a graduate of the history department of Sverdlovsk University, [Ed. Ekaterinburg was called Sverdlovsk in the Soviet times] notes that the first free public schools, which also admitted the children of peasants, were established in 1721 in factories in Ekaterinburg under the envoy of Peter the Great, Vasily Tatishchev. "By 1757 there were no more illiterates among the factory population," emphasises Roizman. He still feels Ekaterinburg is a uniqueplace today and that its special identity has been preserved.

Yevgeny Roizman's vocation as a collector, guardian and promoter of Ekaterinburg artistic heritage is essentially determined by the location of his home. The building where he now lives and where the Museum of the Nevyansk Icon is located, stands on the corner of Belinsky Street and Engels Street where the family of the painter Leonard Turzhansky (1874–1945) lived in a wooden house before the revolution. Between 1919 and 1920, Turzhansky taught at the Liberal Art Studios in Ekaterinburg, and travelled with his students into the countryside to paint en plein air. Roizman sees their approach as a kind of sport: "They sketched against the clock, or from memory. That was the basis [of their practice] and this method still exists today. when you see works by artists from Sverdlovsk - now Ekaterinburg - you can be sure that the artist was working with a portable sketch-box easel".

In Roizman's collection there are over seventy oil paintings and a few hundred works on paper by Vasily Denisov (1862–1922), a pupil of Konstantin Korovin (1861–1939) and Valentin Serov (1865–1911). There is the estate of artist Alexander Khrebtovich, a descendant from a dynasty of tsarist naval officers who returned to the USSR from Shanghai after World War II. After the 1917 Bolshevik revolution, his grandfather steered the warship Patrokl from red Vladivostok to Nagasaki, and his family moved to Shanghai. From 1947 Khrebtovich lived in Ekaterinburg. "He was not recognized by the Union of Artists. He subtly depicted Ekaterinburg from a variety of perspectives, painting houses and streets that are no longer look familiar to us," Evgeny Roizman shows works that have just returned from the restoration workshop in the Museum of the Nevyansk Icon. "I plan to do a small exhibition of his work, to rock it on my social networks where I have one and a half million subscribers, I want to bring the artist’s name back from obscurity into the history of art”.

One more discovery in Roizman’s collection is the archive of artist Alexander Mineyev (1902–1970). Roizman came across it in the flat of Alexei Mosin, a historian and lecturer at the Ural University an old friend of Misha Brusilovsky. "The hallway in the flat was full of canvases," says Yevgeny Roizman, "It turned out that Mineyev had lived there, and after his death his works were simply stored in the attic for many years. But the attic was in a state of disrepair, theartworks were stained with tar used to fix holes in the roof and were about to be sent off to a rubbish dump". Roizman took the archive. Restorers from his workshop removed the tar and cleaned the paintings. The collector found out many hitherto unknown details Alexander Mineyev’s biography: that he had studied in the Ekaterinburg studio Proletkult, worked in the studio of Leonard Turzhansky, collaborated with Ivan Slyusarev (1886–1962), and worked as a set designer at the Proletarian Theatre of the Verkh-Isetsky Factory. "Suddenly, three pictures stood out from the crowd: one was called 'In the Path of the Retreating Enemy, 1943, Liberated Kupyansk'". Mineev had created a series right at the frontline of World War II. These works were restored, and exhibited and add another chapter to the cultural history of Ekaterinburg.

Rediscovering names of artists long since forgotten and working directly with artists' archives is something that Roizman particularly values. He first became familiar with the local art scene at the Ural State University of Architecture and Art, where he performed at poetry evenings. "Around artist Valery Gavrilov (1948–1982) there was a coterie of young and talented artists and in this circle of students, Gavrilov was the undisputed guru, the father of the underground," says Yevgeny Roizman. Works by Valery Gavrilov, and Andrey Ilyin's (b. 1953) ‘Don't Stop Me’, and Igor Shurov's (b. 1958) ‘Lantern’ were among Roizman's first purchases.

On his personal journey as an art collector and philanthropist, Roizman recalls how Misha Brusilovsky said to him once: "Zhenya, you did a very good thing in buying paintings from living artists. An artist is of cousre very pleased when his/her work is shown in exhibitions or published. But for all artists the number one recognition is when his or herpaintings are bought." By the mid-1990s, Roizman had developed an exceptional collection of Sverdlovsk unofficial, underground artists.

It was in 1995 that Yevgeny Roizman first announced his ambitious plans around building a collection of contemporary art from the Urals. At the time there were no such works in the holdings at the Ekaterinburg Museum of Fine Arts. They were sceptical about how realistic it was to even assemble a collection, telling him, “There is no underground art in our collection at all, we never tried to acquire it and now everything is in private collections and has been taken abroad. Although the museum has money to buy them, there are no works left to buy".

Roizman has found his experiences and dealings with the city’s art museum disappointing despite the fact that in 2012, he donated his Museum of Naive Art to the Ekaterinburg Museum of Fine Arts. "I have travelled a lot. In 2010, I saw the International Museum of Naive Art in Nice. In 2011, I saw the Art Brut Museum in Lausanne. I suddenly realized that I could do even better and I told the Ekaterinburg museum: I am not giving you the paintings, because I know they will stay in storage for another century. So I will give you a ready-made museum. I created it and handed it over to the city. And I continue to advise and help with acquisitions." Sadly and inexplicably since 2012, there has been no mention of the name of the founder at the museum. A plaque on the façade was promised, but it seems for political reasons this did not happen. Then they promised a plaque on the door of the founding director's office. "This is absolutely fine for me," says Yevgeny Roizman, "I'm ready to give them my library on naïve art, which I have been collecting over 20 years. But time is passing: Well, you understand, Evgeny Vadimovich…"

"A museum does not have a soul, but a collector does," says Roizman trying to explain the fundamental differences in collecting and presenting art, the institutional versus the personal initiative. He mentions the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow and how he feels it became the most important collection of national art because it was gathered together and funded by one person, Pavel Mikhailovich Tretyakov. However, for all the difference in approach between privatecollections and museums, for Roizman the future fate of his collections lies in handing them over to the city.

Nevyansk Icon Museum

Ekaterinburg, Russia

Ekaterinburg Museum of Naive

Ekaterinburg, Russia