Filippov’s Journey from Land to Paper

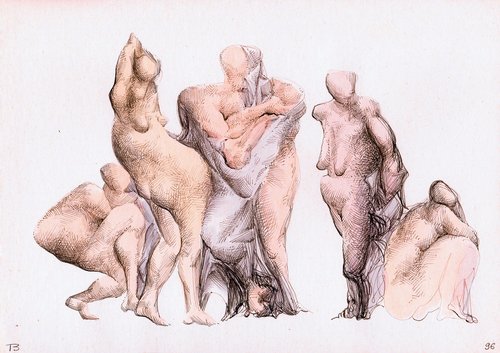

Dima Fillipov and Wika Malkova. Image from Art Uzel website. Courtesy of Elektrozavod gallery

Millennial artist Dima Filippov’s debut solo exhibition in London’s new Art4 Gallery captivates British audiences with a recent body of abstract work where his horizon has moved from the Russian steppe to a sheet of paper.

One of the great American pioneers of land art, later seen as a product of the 1960s interest in ecology, Nancy Holt (1938–2014) once opined that America was germane to this movement because of its sheer vastness. The American land artists travelled to far flung places in a kind of escapist bid to find remote sites for their monumental works, particularly in the American Southwest, like Robert Smithson’s (1938–1973) iconic ‘Spiral Jetty’ and Holt’s ‘Sun Tunnels’ in a ghost town in Utah. Despite all its land stretching across seven time zones, Russia is not generally known for its land art (with the exception of Polissky’s Nikola Levinets) but a young artist living in Moscow is pioneering a new, homespun version, in which he explores the legacy of the recent Soviet past as part of the landscape, preferring the personal over the monumental in a country where the individual is increasingly subsumed by the state.

Dima Filippov (b.1989) was born in Gornyak, a small town close to the border between Russia and Kazakhstan, in what is known as the Altai Krai, a kind of borderland of steppe and mountain between Russia and Asia. He co-founded an artist run space in Barnaul before moving to Moscow where over the past decade he has been involved in grass roots, artist-run initiatives, continuing there to explore his identity as an artist through his remote, small-town origins. He is both an artist and a curator, loves collaborating with others, and until recently his art practice was always a social activity.

Even in the Russian capital, Filippov has lived and worked on the periphery, shunning large scale art institutions - whether state or privately funded by the oligarchs. He made his mark early on in the capital via a witty visual statement alluding to one of his American heroes, Richard Serra with a readymade iron sculpture ‘Unreliable Construction’ (2014), consisting of a large section of a former oil and gas pipe which he bought and casually leant against the wall in an exhibition at Abramovich and Zhukova’s Garage museum in Moscow to show up what he sees as a domestic contemporary art scene spoilt by oligarchic support. His reputation has grown such that now he is courted by institutions like the Garage (although it is currently not functioning as a museum or gallery space) despite debunking authority in an environment hostile to open expression.

In London, Filippov’s debut solo exhibition could not be taking place at a more difficult time, with cancellation of many Russian cultural shows and concerts around Europe since the start of the War. Russia’s contemporary artists have found themselves between a rock and a hard place, unwelcome either in Russia or abroad, it is a precarious existence, which has forced many artists into silence or emigration. Filippov, who today lives and works in Moscow, and his gallerists, couple Igor Markin and Liza Bobkova are undeterred, opening the show at their new Art4 space among a nest of galleries at Cromwell Place this month.

Filippov’s work most often draws from his family history. During the Soviet times, his father worked as a miner, and after perestroika, along with thousands of others, was made redundant when the local mine closed down in 1994. Russia in the mid 90s was awash with workers not receiving wages, balancing on the brink of redundancy, many in towns named monotowns which were often only supported by one local industry. While the West courted and celebrated the new era of privatisation, which later turned out to be problematic, there were across Russia countless stories of stagnation and economic hardship. Filippov brings his own very personal dimension to land art practices, looking at the land through the prism of his own family history. In a series of video and photographic works made over four years called ‘Sketches of my Father’ (2009–2013) father and son visited the site of the mine his father once worked for, taking photographs, scouring the ruins of the mine and then blending those with photos from his father’s own archive. Ironically, it is through this personal, individual approach, that I think the artist achieves a certain universality, creating an intimacy and authenticity in his artwork to which we can all relate. As Filippov puts it in a recent telephone conversation, ‘The story of one person is more universal than big political events’.

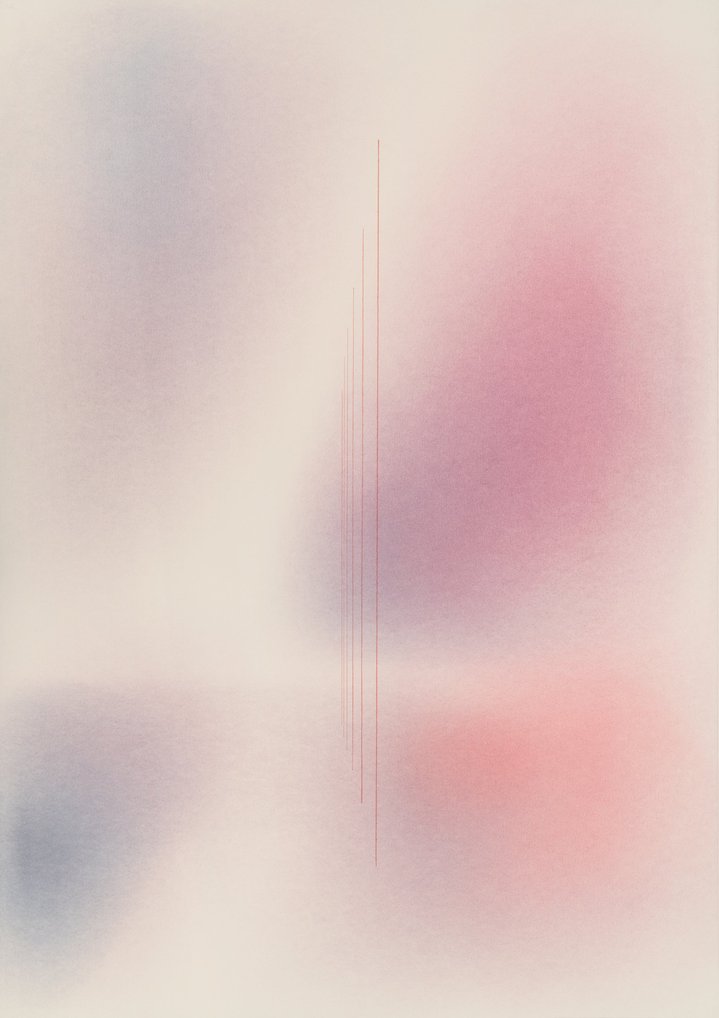

Like many, Filippov’s world turned upside down around the time of the pandemic, but it seems that for him this change came more out of an inner necessity. He suddenly found himself turning away from collaborating with others, shunning the kind of collaborative performances, curatorial initiatives or large-scale installation works for which he had been known, and over the past few years he has been searching for a new visual language, the fruits of which are exceptionally beautiful, powerful yet subtle abstract drawings which are on display at Art4. Although the American land artists are among Filippov’s heroes, he is very much an heir of the Moscow conceptualists, these recent works and their preoccupation with the horizon conjure up the work of Eric Bulatov (b.1933) and Oleg Vassiliev (1931–2013).

We talk about his current exhibition in London, the title ‘Brink’ a translation of the Russian word ‘Krai’, as the exhibition was called in Moscow, where other works from the same series were shown last year. The word ‘Krai’ carries echoes of the artist’s home (Krai referring to geographical and administrative regions of Russia which are at the edge of the country as in Altai Krai), the poetics of a sense of remoteness, the existence at the edges of something. To be on the brink of something can invite a sense of impending doom, or excitement, and I am not certain that Filippov’s vision is either quite so pessimistic or slam dunk. At his most serious when not building visual puns, there is both pathos and hope.

What does his father think of his art? He likes it, but perhaps not everyone wants to look at the past so closely. In one of his performative works, Filippov and his father went back to a plot of land their family had once owned in the Altai, which they sold to developers. While they were both combing the ground for detritus, the artist like a divining rod searching for a past long since gone in the flood of time and historical events, every now and then his father would plead, ‘Come on, hurry up, it’s time to go home!’.