Erik Bulatov: “Freedom is the Road”

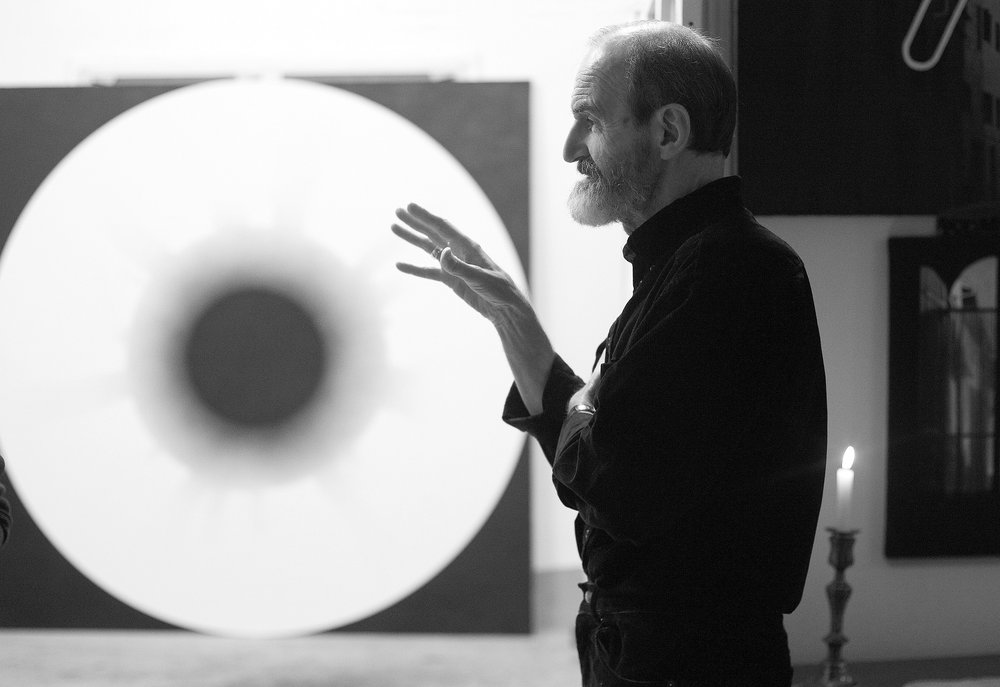

Erik Bulatov. Photo by Vladimir Sychev, courtesy of pop/off/art gallery

An artist who seeks to transcend the borders of space and the limitations of language

The Yeltsin Centre in Ekaterinburg is a bizarre shopping mall-cum-museum, the only institution in Russia dedicated to its first President. It has a nostalgic and slightly surreal air, fitting for a memorial to a political leader who tried hard to bring democracy to Russia and lived long enough to see his efforts nullified. After observing the family memorabilia and archival footage, visitors step into a huge hall with floor-to- ceiling windows and an enormous painting covering the entire wall. The sight is arresting. It is an image of a blue sky with scattered white clouds and huge letters bolting away from you, as though sucked into thin air by an invisible, yet irresistible force. The letters form the word СВОБОДА (FREEDOM), and instantly one feels the almost physical but elusive presence of a powerful entity: fascinating and vital yet totally unreachable.

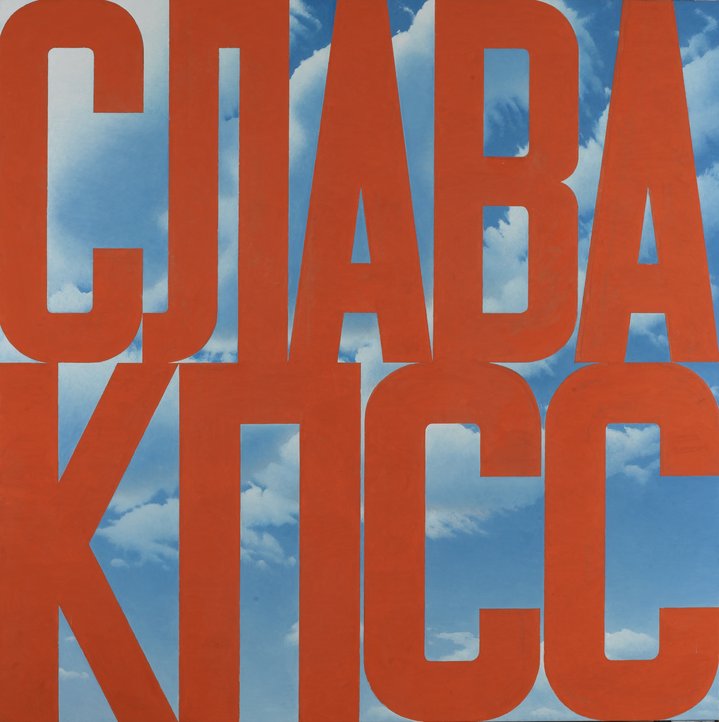

The painting, commissioned by that museum, is the work of Erik Bulatov, now 85 and based in Paris. An exhibition of his drawings and sketches is on view at this centre until 20 January, offering a rare chance to see the inner workings of the artist’s mind. This is the first time Bulatov has staged a graphics-only exhibition, although drawing was always an important part of his work. He even used to make a living off it back in Soviet era, illustrating children’s books together with his friend Oleg Vassiliev, another important figure of the underground art scene. Bulatov turned to illustration shortly after graduating from Moscow’s Surikov Art Institute in 1958. “I started it so as not to accept government commissions,” he says. This was about the only form of artistic freedom possible within the Soviet system: Ilya Kabakov and Viktor Pivovarov also used book illustrations as an opportunity to earn their daily bread while avoiding the Soviet propaganda industry. Bulatov divided his years in two: he spent six months drawing princesses and sleeping beauties for Soviet publishing houses and the other six months painting unconventional works that had no chance of being legally exhibited. He tried abstract painting at first, but soon developed his distinctive style that baffles critics by transcending the boundaries of 20th century art “movements.” Take sots-art, photo-realism and conceptualism: Bulatov’s art has lots in common with all of them, but it nevertheless does not quite fit into any of these categories. (He is often called a predecessor of sots-art, a style which subverts and derides cliches of Social Realism in the same way that pop-art reimagines the imagery of advertising and popular culture.) His most famous works challenge our notion of painting as a medium by building unexpected spatial relationships of text and images. Sometimes the words, dramatically foreshortened, bolt off into the horizon, creating a tension that drags the viewer into the painting. Sometimes, they are superimposed over realistically rendered landscapes, as if forcefully blocking them out. The artist often uses slogans of Soviet propaganda or exclamations from ubiquitous “Warning!” or “Welcome!” signs, incorporating all-too-familiar words and fonts with all their flatness and dullness into the sunny, peaceful scenes where dead and hollow words suffocate freedom and life.

“Noble words were on display, but the meanest notions were hidden behind them,” he reminisces. “Ratting on people was called ‘honesty’ while servility was called ‘bravery.’ People’s minds were maimed and deformed, and they cannot be straightened out overnight. In fact, it is our work to fix this.” His works have all the keen sense for the absurd that is typical of sots-art, but without a trace of irony. Bulatov’s vocabulary is not limited to slogans. Other words, both simple and subtle, often grace his canvases, like quotes from the minimalistic verses of Vsevolod Nekrasov, a poet and long-time friend of the artist. Bulatov turned his line “ЖИВУ — ВИЖУ» (“I live, I see”) into a painting which is now often considered the manifesto of his whole generation. Yet the message of his works, whether political or poetic, is both real and misleading. “It is probably easier for a foreigner to understand them,” Bulatov says about his text-based paintings. “The word is mainly a visual image for me. My words have to be seen more than heard or understood. A letter and a cloud are both characters, just like in a play. Their relationships and movements within the space of a painting constitute the subject matter of my works.” Though for a foreigner, seeing comes naturally before understanding, it takes a native Russian speaker a certain effort to dive below the surface. “You won’t understand ‘СЛАВА КПСС’ (Glory to the Communist Party!) unless you notice that there is a gap between the letters and the sky,” Bulatov explains. Maybe that is why his international career flourished when the USSR’s once impenetrable borders slackened during Perestroika. After a succession of solo shows in European museums in 1988, including one at the Centre Pompidou, he was invited by a gallerist to live and work in New York City. He moved to Paris shortly afterwards. He and Ilya Kabakov are the only Russian artists whose works fetch 7-digit prices at auctions. Erik Bulatov often visits Russia and had big solo shows at the Tretyakov Gallery in 2006 and Moscow’s Manege exhibition hall in 2014. He has achieved everything an artist could aspire to, but his quest for freedom seems to be neverending. “For me, ‘freedom’ means being free from social space,” he tells me as we sit in the living room of his Moscow apartment. “Within society, freedom is impossible because ideology of one sort or another is present everywhere — and this is lethal for freedom. I think of it now in a more universal way: for me, freedom is the road. Where does it lead? Probably to the light, I think. That’s why I see a painting as movement through space that goes beyond space!” What immediately comes to mind is the very first word on a painting that he acknowledges to be entirely his own creation, not derived from slogans, posters or poetry. That word was “ИДУ.” It translates simply as “I GO.