Alexander Kronik: more than white paintings

Moscow art collector Alexander Kronik has just published a new biography of Oscar Rabin illustrated with drawings from his own collection. A frequent figure in the underground circles of the 1980s, he does not look back with nostalgia for a lost era.

At the beginning, Kronik never liked being called a collector, but Maria Plavinskaya said to him one day: “You can say it all you want, but you are a collector.” As a young man in 1980s Moscow, Kronik found himself in the creative atmosphere of artist studios. He was a lawyer from a family of lawyers practicing in Soviet Russia in the 1980s. He then spent a decade in Tel Aviv doing the same. Today, back in Russia, he has no desire to work as a lawyer again. He shudders at the thought of it, it seems crazy even: “Bred!” (“nonsense”).

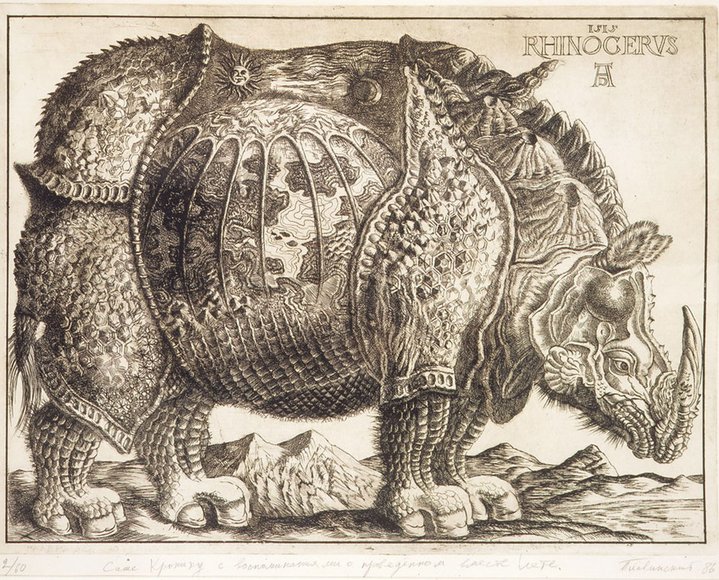

Kronik has just published a book about Oscar Rabin (1828–2018), the impulse behind which was a collection of forty odd graphic works by the artist, early works mainly from the 1960s, which he has acquired over the years. Most had been exhibited already at the Tretyakov Gallery and MAMM, but Kronik said he wanted to “set them down”. Over many long years, he worked slowly and persistently cataloguing them and it finally became his pandemic project and now here it is, ‘Visa to Another World’. He hands me a signed copy. “Why only graphics?” I ask. “I don’t like Rabin’s oils as much as his works on paper,” he explains. I think he might be onto something: Rabin’s oils are very dark; in the works on paper the contrast between the black outlines and the white of the paper lifts the image out of the gloom. He acquired several of them from the Estorick collection at Christie’s. Like many pandemic projects, along the way, there was a sudden tragic loss: his first editor Katya Allenova passed away due to covid last year.

I’m at his apartment to ask him about the book, but take the opportunity see his collection again. We look at a Weisberg (1924–1985) still-life hanging at the entrance to his living room, his most recent acquisition. “The Weisberg once belonged to Nadezhda Mandelstam,” Kronik says as he disappears to grab an edition of Bruce Chatwin’s ‘Utz’ in Russian translation, where, incredibly, this very painting is mentioned. I remind him Chatwin once worked at Sotheby’s. I find the book when back in London and the reference is too good to leave out: “A white-on-white abstract painting hangs crooked on the wall; she [Nadezhda Mandelstam] had just thrown a book at it that displeased her. As Chatwin straightens it, she reflects: ‘Weisberg. He is our best painter. Perhaps that is all one can do today in Russia? Paint whiteness?’”

Kronik’s impressive art collection assembled over nearly forty years and numbering around 700 works is all from a specific time and place. It’s Moscow non-conformist art from the late 1950s until the beginning of the 1990s. He has a taste for figurative and expressive art, not conceptual and most of the artists he knew personally. Curiously, despite the fact it is art from a distinct era, he does not like to dwell on the context from which it sprang. He thinks deeply about how on the one hand his collection reflects the late soviet epoch by dint of its heritage and, yet, he says he has no nostalgia, quite the contrary.

We talk about the show ‘Alternative Spaces’ that just opened at the Ekaterina Foundation, where there is a sense of nostalgia for the late Soviet era in particular. “I don’t have any association of time through these works,” he says, looking around at the walls in his spacious living-room. “I just do not see the context of time in these works – maybe when I look at a Bulatov ‘Vkhod-Vkhoda Nyet’, I see it there. I frame all my works carefully,” he says, referring to a popular practice today for keeping original frames, riddled with woodworm or with sloppy paint. “I don’t like to see them [the works] in communal apartments.”

Of course, he has pulled them from Soviet obscurity where they were underground, not literally, but where they were hidden. I stop to think: Don’t we want to elevate the things that we salvage and do our best for them? That is what he does, these are his scales of justice being put to use. He brought these works and these artists out into the light; he trusts and believes in their importance. When he started out as a collector in his youth, he had a vision: he saw how the impressionists were collected by their contemporaries and he decided to do the same in his time and place. No one can say these artists got justice during their lifetime, even now prices are wobbling on the market. But, it is far more than about market value: it is about public recognition and people are only starting to see value in them. Many of the artists have already long since passed away.

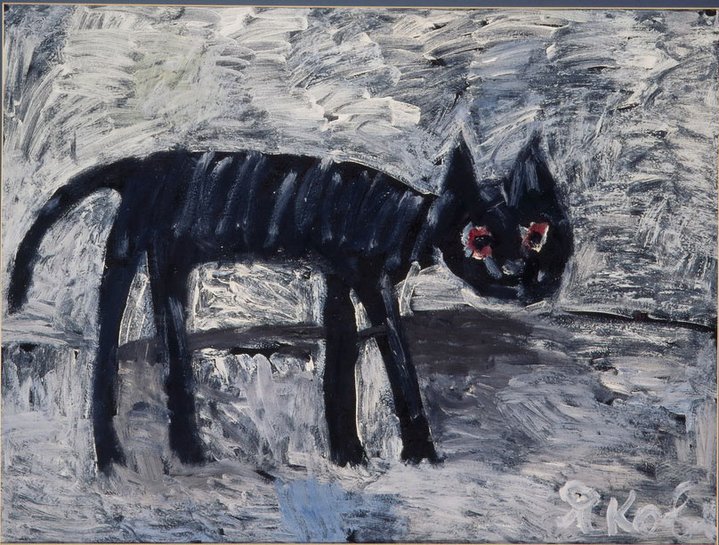

His collection elevates artist Vladimir Yakovlev (1934–1998) above all others and like most collectors who take a particular liking to a particular artist and have a large collection of their work, Kronik is something of an authority. I see many works dotted around his apartment, one of which looks like a Pollock. Yakovlev did not spark a whole movement, but it is hard not to be touched by these little works, this one dating to the 1950s, when Stalin was still alive; Pollock was doing his best work then. Yakovlev spent much of his life in psychiatric institutions and was extremely visually impaired from his mid 30s onwards.

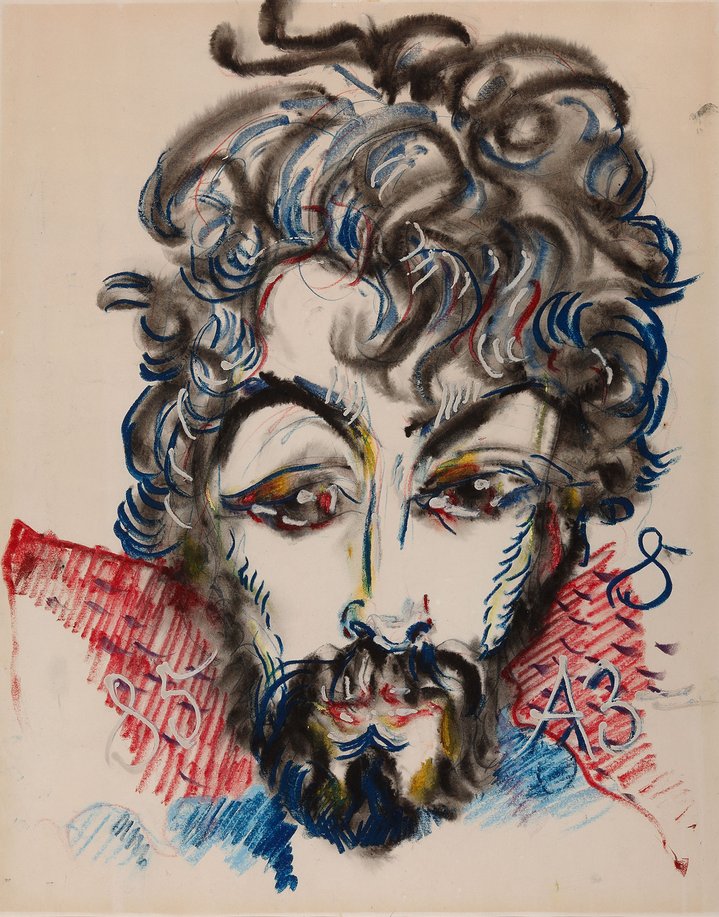

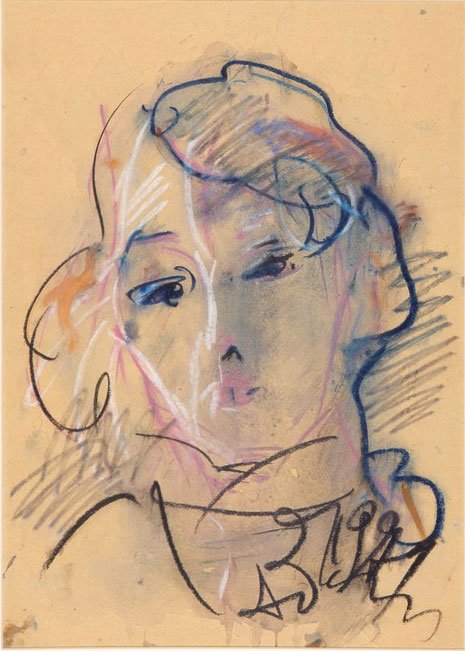

Art historian Katya Bobrinskaya calls it a “living collection”. It grew organically from Kronik’s personal encounters and the life which surrounded him and there were no market forces influencing his choices. The title of the catalogue of his collection published a decade ago, ‘Svoi Krug’, hard to match in translation, captures exactly this phenomenon. ‘Svoi’, a possessive pronoun which confounds most students of the Russia language, at once indicates possession, but also identification with the object; and ‘krug’ – a circle. One tiny painting in his collection called ‘Tuman’ (eng. ‘fog’) is a joint work with Zverev, signed by both him and the artist on the back. He turns it around to show me. There was a fog in those artist circles, the edges of one artist and another blurred and there was also a place for intelligent, curious-minded people like Kronik who just fitted in.

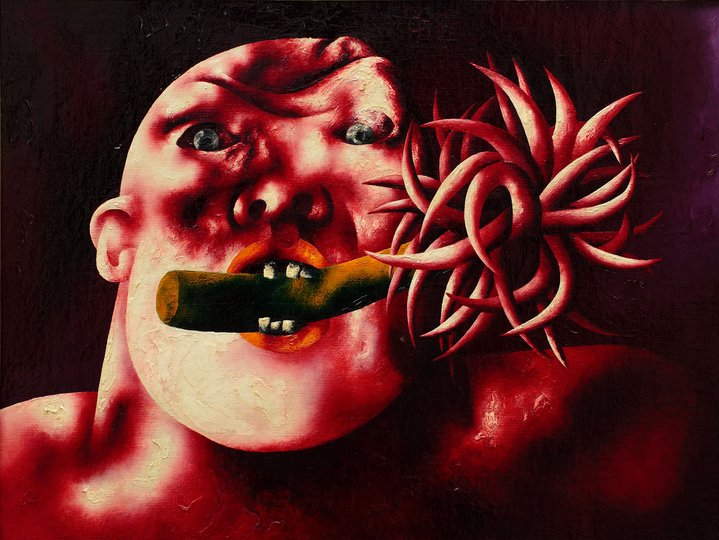

If Yakovlev is his favourite artist, he found a special personal connection with Anatoly Zverev, who painted his portrait many times. If there is any artist whose work can be described as anything but white, it is Zverev (1931–1986), with his use of bold, bright colours applied at times directly from the tube in its strongest hues. Kronik’s first acquisition ever in 1984 was a work by Zverev and he is pleased to see the artist’s reputation is finally being restored today through projects such as Opaleva’s Zverev Art Prize. As for Yakovlev, whose work he adores, he reserves the most praise. We leaf through albums with the ‘cat eating a bird’ motif so loved by Yakovlev, “inspired by Picasso” explained Kronik. Yakovlev: the bird being eaten by his own psyche or the Soviet cultural straitjacket, or just those laws of nature where nothing is fair. High up on the wall I recognise a Yakovlev flower painting he bought at a Sotheby’s auction twenty years ago, when I was still a young art expert. Two flowers side by side look anthropomorphic, I remember it well. “His time will come,” says Kronik, although, in an era which loves large bombastic images, I hope he is right.

The collectors he most admires and looks up to are Igor Sanovich and George Costakis, “They were not multi-millionaires, but just look what they did!.” He thinks the rise of the art market has had a spoiling effect – he talks about how, years ago, he would go to an exhibition and not think about what something might cost. “Now you have to say, ‘how much is it?’” Kronik is plausible. He bought art at a time when it was not valuable. When he left Russia for Israel in 1990, the art was nearly worthless, no-one wanted it. Only with the past generation has this begun to change and the value of his own collection is rising, but who could have predicted that 30 years ago?

Visa to Another World. A Biography of Artist Oscar Rabin

(Russian only)

By Alexander Kronik