Dmitriy Alekseyev and the Language of Traces

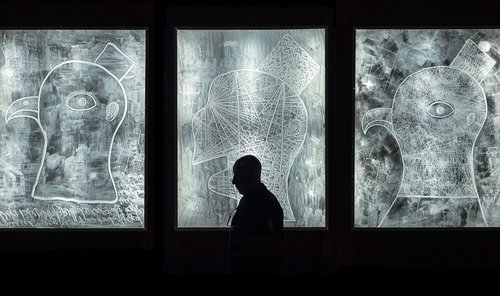

Dima Alekseyev. Pathway, 2025. Courtesy of the artist

Russian artist Dmitriy (Dima) Alekseyev’s new exhibition Pathway opened last week at Crossing Art gallery in New York’s Chelsea neighbourhood. Bringing together a new body of large-scale works, the show marks a turning point in the artist’s practice, one in which traces, paths and physical engagement with material come to the foreground.

For Dima Alekseyev (b. 1963), the work begins with physical contact. “I was trying to move through them,” he says. “There’s this sense of tactility – as if I’m passing through the landscape with my feet, conditionally speaking. I touch it, trample it, enter into it, trying to form some kind of relationship with it.”

The recurring motif of the path – traces, cords, bindings – grows directly out of this process. Everything is connected; something is always left behind, tied again, and carried forward.

By the time Alekseyev left Russia, traces had become a central motif. Footprints, smears, worn paths – marks left not by depiction but by action. In Nizhny Novgorod, he created his first “trampled” portraits, formed entirely through accumulated impressions.

This approach culminates in ‘Pathway’, a series created for a Chinese-owned gallery in New York. Commissioned to develop a project linked to China, Alekseyev avoided overt references and focused on the Daoist idea of wu wei, commonly translated as “effortless action.” “I can’t fully grasp it from the inside,” he says. “I can read about it and shape my own understanding – as a European.”

That idea took the form of landscapes – though not landscapes in a descriptive sense. Working with polycarbonate cement, aluminium, acrylic latex caulk, plastic mesh and pigment, Alekseyev has created surfaces that resemble terrain shaped by pressure and time. The works are dense and layered, often recalling plaster walls worn down through repeated contact. The material itself determines the image. Alekseyev does not impose a form so much as follow what emerges.

The motif of the path runs through the series: cords, bindings and crossings that suggest continuity and connection. Each step leads to another. Alekseyev describes the process as tactile and bodily – as if moving through the work rather than standing outside it.

Alekseyev never signs his works; the trace itself functions as a signature, echoing the red seals traditionally stamped onto Chinese paintings – a reference that appears directly in the crimson marks punctuating several canvases.

Although ‘Pathway’ marks a decisive move toward abstraction, the human presence has not disappeared. In one rare work, the human form briefly resurfaces, framed by a window, before dissolving again into matter. Seen alongside earlier figurative pieces from ‘Anonymous Faces and Boulders’ series, the trajectory becomes clear: Alekseyev is moving from the observation of the human body toward the forces that shape it.

Dmitriy Alekseyev has changed several careers in his lifetime. After graduating from the Textile Institute in Moscow in 1986, he began working as an art director with leading Soviet film and theatre directors, including Mikhail Kazakov, Alexander Proshkin, Konstantin Khudyakov, Vladimir Mirzoev and Rustam Khamdamov. In the 1990s, Alekseyev left the cinema and turned to painting. For several years, he was represented by the well-known Moscow-based Kino Gallery, one of whose founders, Polina Lobachevskaya, later became artistic director of the AZ Museum.

By 2006, Alekseyev made a decisive break with his earlier work. “It was a long story,” he said, “but at some point I decided to quit the style I had been working in.” That period was defined by what he describes as a form of impressionism – not in a literal or academic sense, but ideologically. The work was complex and highly successful: he said he does not own a single piece he made before 2006. “Everything was sold,” he added.

After stepping away from painting, Alekseyev opened an architectural studio in order to support himself. Architecture provided him with a living in Moscow, while painting receded into the background. Over the years, Alekseyev made numerous attempts to return to art, but what he was producing felt too familiar. He could see exactly where it was coming from. “It’s not enough to invent a language,” he said. “You also need something that makes it click.”

By 2010, Alekseyev had become deeply involved in festival work. Alongside running his architectural studio, he began organising large-scale cultural events. New festivals followed in quick succession, sometimes every few months. In 2013, he co-organised a major international festival at the Museum of Decorative Arts. It brought together prominent artists from the UK, the US and Italy, and generated some controversy: a large outdoor sculpture installed in front of the museum was dismantled within hours.

This experience fed directly into one of Alekseyev’s most ambitious projects – a public art festival in the industrial town of Vyksa, known as Art Ovrag (currently Vyksa Festival). Conceived together with partners from the city and its cultural institutions, the festival was driven by a belief that contemporary art could reshape the urban environment and public life.

Over several years, Alekseyev and his team transformed Vyksa into a site of large-scale public art, inviting leading graffiti artists, architects and choreographers from across Russia, Europe, Israel and the UK. “In four years,” Alekseyev says, “we put the city on the map.”

Seeing large-scale murals and the radical freedom of the festival scene was a turning point for Alekseyev. Surrounded by artists who operated without restraint, he realised that this was the scale that suited him. Drawing on his architectural background, he began to treat urban infrastructure as a structural framework for painting. Bridges became supports from which he suspended vast mesh surfaces. “I thought of the canvas as the sky,” he recalled. “I wanted to paint in the sky.”

He began in Moscow with smaller bridges, gradually moving to increasingly ambitious interventions, including participation in the Moscow Biennale with a show at the Museum of Architecture. He also organized the guerilla public art festival Luch, which faced increasing opposition from the government.

Alekseyev’s last project before he moved to the US was in 2016 in the Arsenal Museum in Nizhny Novgorod. It was as he was preparing to leave Russia that the motif of traces first emerged in his work. “When you’re leaving and you have nothing,” Alekseyev said, “what can you take with you? You can only trample your portrait into the ground – and walk away.”

After moving to the United States, Alekseyev settled in Atlanta. His first art project there was with the Millennium Gate Museum, a private institution housed within a monumental triumphal arch. Invited to contribute to an exhibition marking the legacy of the Atlanta Olympic Games, he developed two site-specific works. One showed ordinary people casting the shadows of Olympic heroes. The second imagined the athletes reaching toward a departing “boat of time,” a metaphor for history slipping out of reach.

Later Alekseyev proposed to suspend large-scale work over the river from Highway 400 in Roswell, a suburb of Atlanta where he lives. The City Hall agreed and Sky Maintenance was born, a project which imagined human figures repairing the sky – as if it were something worn out and in need of care. In the United States, Alekseyev has returned to painting and has since held several exhibitions at the MORA Museum of International Art in New Jersey, where he is currently participating in a group exhibition ‘Three Artists, Three Visions’.

Dima Alekseyev. Pathway

New York City, New York, USA

5–28 February 2026

Three Artists, Three Visions. Dima Alekseyev, Emil Silberman, Avroiml Bisslemacher

MORA Museum of International Art

Jersey City, New Jersey, USA

7–15 February 2026