Boris Mikhailov’s major retrospective in France

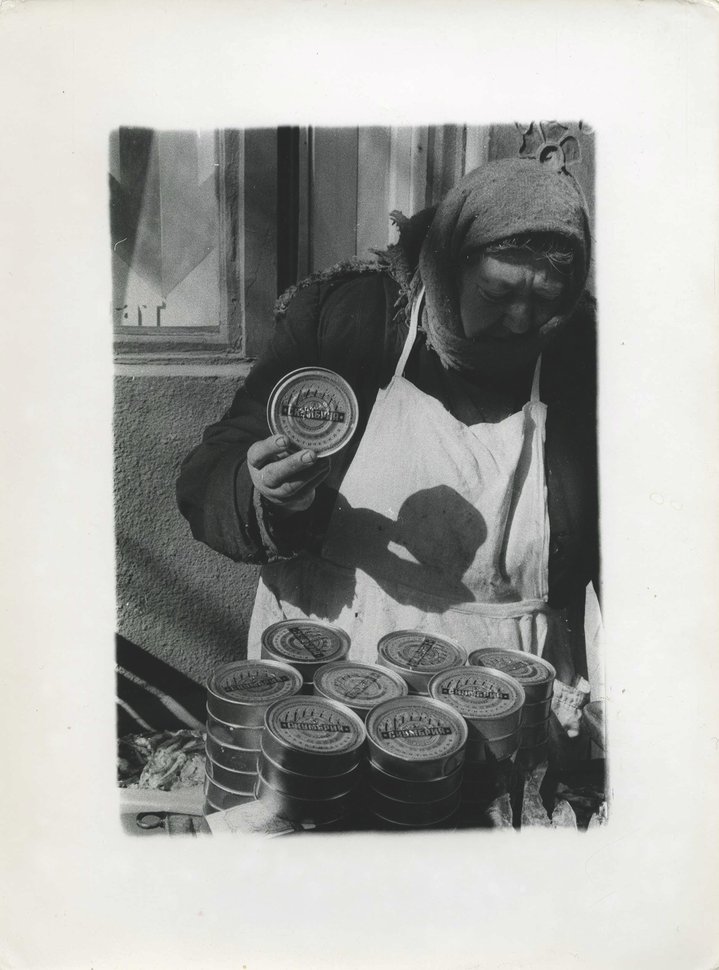

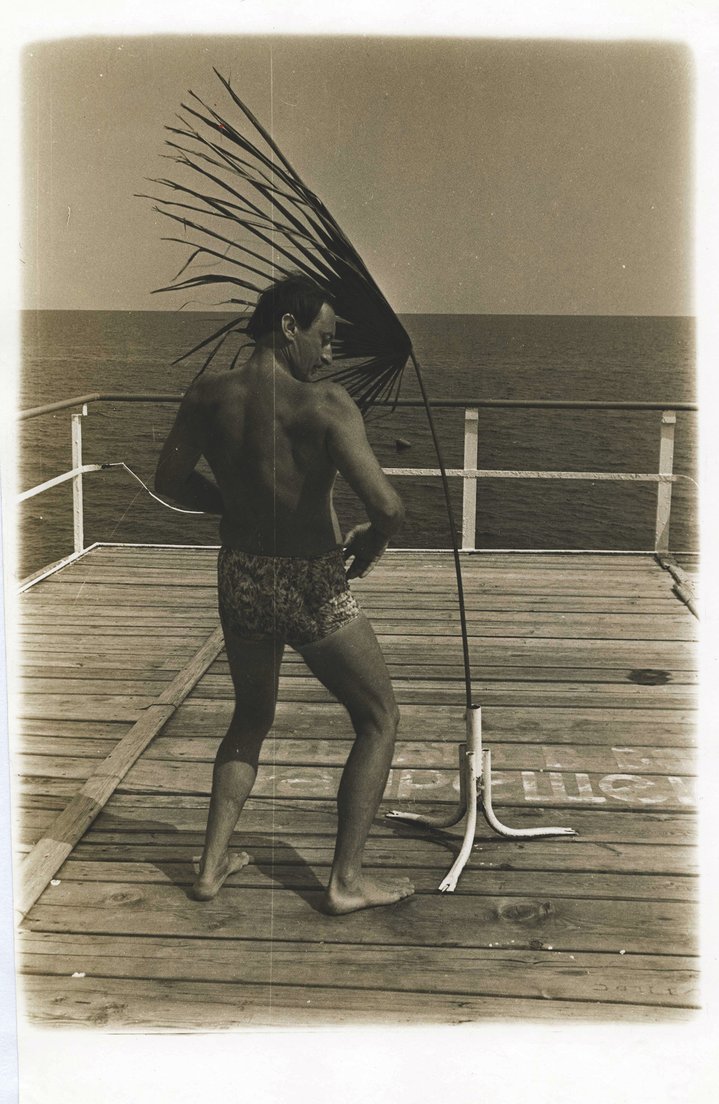

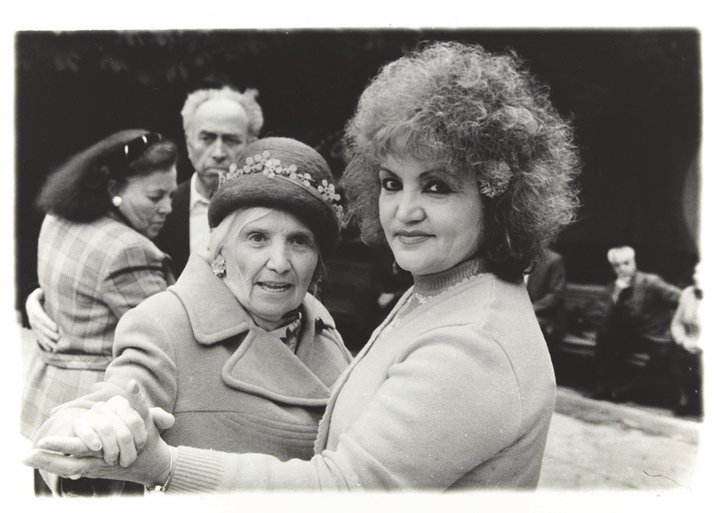

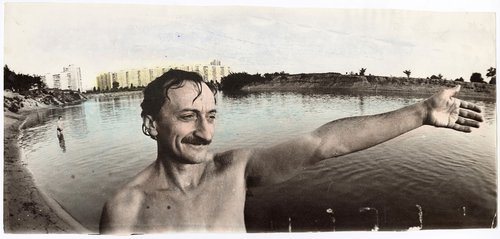

Boris Mikhailov. From the series 'Crimean Snobbism', 1982. Silver print, sepia tone, 15x20 cm © Boris Mikhailov, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

A major retrospective of Boris Mikhailov will open at La MEP in Paris on 9th September 2022. Covering three floors, twenty series, eight hundred works, the event has been postponed by a year due to covid restrictions, but now the finishing line is in sight.

Mikhailov, born in Kharkov in 1938, is by far the most internationally acclaimed photographer from the former USSR. Throughout his distinguished career, the awards have kept coming: winner of the Hasselblad Prize in 2000, the Citibank Photography Prize in 2001, the Goslar Kaiserring Award in 2015, among many others. He represented Ukraine at the Venice Biennale in 2007 and 2017 and has had many solo exhibitions around the world including at MoMA in New York in 2011, and C/O Berlin in 2019.

Boris Mikhailov's long career in art began in the mid 1960s when he volunteered to make a documentary about a factory where he was employed as an engineer. Through working with technical testimonies and documents in the archives, he realised the intrinsic power of documentary photography, even (if not all the more so) bad, random, technical photography. He joined a local photographic club, but refused to follow what was fashionable at the time among amateur photographers: lyrical reflections of everyday life. The official press, with its rote vivacity, was and still is all the more alien to him.

By 1968, Mikhailov had risen to the post of head of the photographic laboratory at the plant, which gave him access to photographic material. There was a real sexual revolution going on in Kharkov at that time; like so many other photographers, Mikhailov was also shooting nudes, but they were not romantic studies inspired by the Lithuanian school, instead an irreverently cheerful series called ‘Susie and Others’. Eventually his bosses discovered these pictures and the artist was summarily dismissed. However, by this point, he had made several important discoveries.

Firstly, it turned out that an occasional, domestic photograph could carry a meaningful protest and anti-Soviet charge. “I used to define the bad quality of my images by the Soviet context: a normal Soviet image for me had to be worse than a normal one. It had to be of average Soviet quality. Average Soviet bad quality became part of my aesthetic,” he explained in a conversation with Viktor Marushenko. Essentially, Mikhailov went against photographic tradition, adapting the medium to his own needs and in doing so entered the field of contemporary art. Thus, he made the colour of visual propaganda and mass marches into his hero in the ‘Red’ series, 1968–75. This was an example of a conceptual anthropology that was developed in parallel by Vitaly Komar (b. 1943) and Alexander Melamid (b. 1945) within the framework of Sots Art, a title Mikhailov also used later, calling one of his series ‘Sots-art’, 1975–85.

Secondly, Mikhailov discovered the colour film ORWO CHROM which was produced in the German Democratic Republic and available in the USSR. A randomly thrown stack of transparencies led to an interesting superposition of images. Thus appeared ‘Yesterday's Sandwich' series (1968-75). These new images looked surreal, but they also accurately described the doublethink of an era, a parallel existence in multiple layers. In the 1970s, Mikhailov performed live demonstrations of such overlays in photography clubs to the music of Pink Floyd. It was a double Fronde and a chance to feel like a real rock star: up to eight hundred people attended such demonstrations. Already in the noughties, he edited a five-minute video to songs from the Pink Floyd album Dark Side of the Moon for these exhibitions. It's hard to imagine the reactions almost half a century ago, but on the whole, the 1970s was a time when people all over the world had a passion for the new, and stadiums were packed with bands playing experimental music.

“... It was a time when there was a feeling that we're going forwards. Everything is at that beginning, which was in '68. The aesthetic line takes off from there. And the literary or narrative line develops according to each individual situation: you are lucky or not to shoot something important. And my analysis was: I get lucky, everything is good. There's nothing to be embarrassed about, nothing to feel shy about: my analysis tells me that everything was right. [...] Of course, we are only talking about the USSR; we did not know what was happening abroad,” he told me during a private conversation with him and his wife Vita in 2019.

Overlapping became for Mikhailov one of the cornerstones of his technique. Transparency and ambiguity are dimensions which in one way or another have accompanied him throughout his life. The initial images could be “bad quality”, beautiful or ugly, but overlapping dialectically they became “super quality”.

As early as 1971, Mikhailov began collecting what were popularly called luriks. This was a folk, vernacular technique that gave some photographers a steady, if illegal income. Very few Soviet families had large colour photographs at that time, so people would go door-to-door and offer to make a colour photo from a small black and white card into a big one. E.g., they took a passport photo and coloured it. In 1981, Mikhailov realised that this collection of other people's photographs could be appropriated and assembled into his own series. All the more so since he had collected the most striking examples. The principle of using other people's images had already been invented by him.

In parallel, in the 1970s, postmodernist theory was developing in the United States though articles and exhibitions by curator Douglas Crimp, as well as works by Richard Prince, Louise Lawler and others, but of course Mikhailov did everything independently. To this day, The Luriks (1971–85) are some of his best known works.

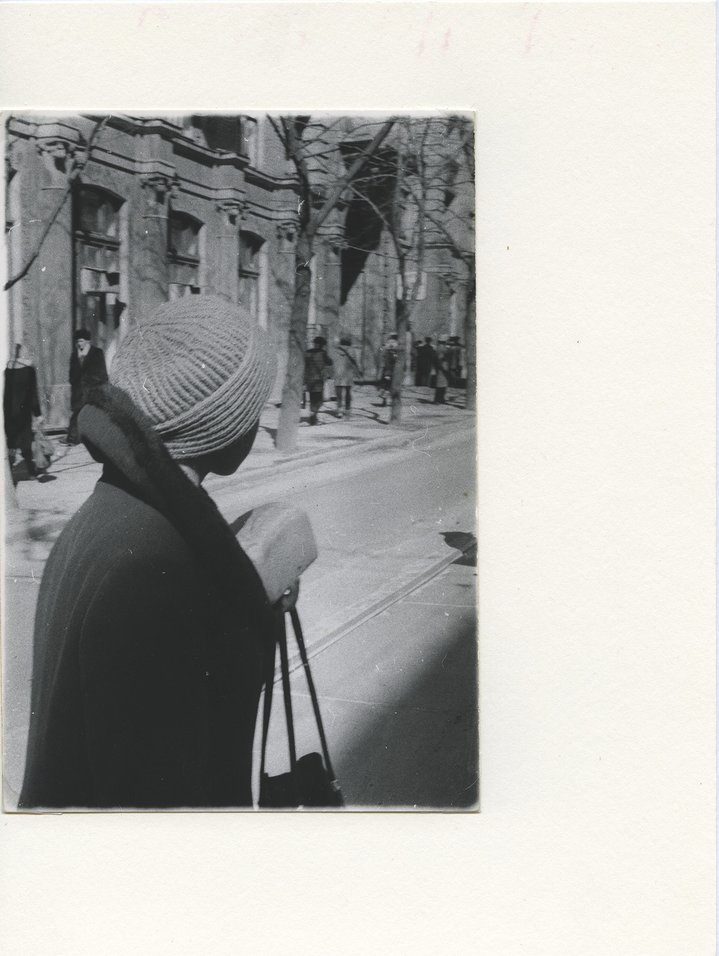

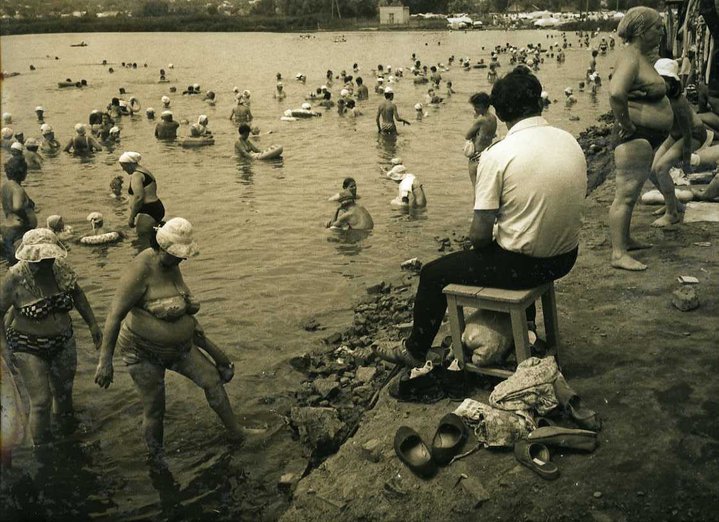

At the end of the 1970s, Mikhailov joined the circle of Moscow Conceptualism and became friends with Ilya Kabakov (b. 1933). Like Kabakov, Mikhailov thematizes Sovietness and the Soviet, though he pursues a different path: “Our photographic life is special. This peculiarity is the reason why it is the only thing that should be photographed,” he confessed to Viktor Maruschenko. At this time, he turns to black and white film and among others makes the series ‘Fours’ (1982–83), photographs assembled in groups of four were a visual portal into a special space, characteristic only of that place in time. ‘Unfinished Dissertation’ (1984–85), a set of sheets with cards glued in pairs, with handwritten texts looked like random accounts of an obscure life, a mystery, but also felt reassuringly bureaucratic. ‘Salt Lake’ (1986) was about people bathing in some kind of muddy puddle that looked like an industrial sump, supposedly with healing properties.

As the USSR became more open, international curators started to visit Moscow and this led to an increased interest in unofficial art and photography. The book ‘Another Russia’ published in 1986, which included Mikhailov's photographs, was a breakthrough. A number of other publications followed, and many photographers began to exhibit abroad. However, the euphoria of liberation from the bonds of communist ideology was followed by the collapse of the country and a huge economic crisis across the newly formed countries. At this time, Mikhailov was working in his native Kharkov. Thus appeared ‘By the Land’ (1991) and ‘Twilight’ (1993). “I used to shoot differently. And now I have the right to shoot bad things for myself. Before, ‘bad’ was like a snatched incident, and it was understood as anti-Soviet. And now there is a lot of this bad stuff, it is a trend. And it has already become a political thing.” as quoted in the catalogue of the ‘By the Land’ 1993 exhibition at the XL Gallery in Moscow.

In the late nineties, Mikhailov produced ‘Case History’, one of his most striking and discussed series. Technically, it is almost a fashion shoot, where the models are the declassified, trodden on by this new life; drinking, homeless people and skinny, glue-sniffing kids who posed for Mikhailov for a fee. According to the artist, they were the real heroes, people on the front line of social change yet the first to perish. To show this series off best (and as they were displayed at the Saatchi gallery in London) prints of enormous size were made that spanned the entire wall, overwhelming a viewer, and at the same time enabling one to perceive these unlikely heroes with detachment.

Boris Mikhailov continued the story of social change in his hometown with his series ‘Tea, Coffee, Cappuccino’ (2000–2010) and others, such as his ‘Tempation of Death’ (2014–2019) shown as banners on the streets of Basel in 2022 during the Art Basel fair. It is a set of double works where the right side is opposed to the left, and on one of them there is something dead (not necessarily in the literal sense). The series took on a particularly sombre context after the 24th of February this year.

Today, well into his eighties, Mikhailov remains active, with a number of gallery and museum exhibitions each year, and new books being published. “I'm on a kind of wave, and that wave hasn't been caught up with yet. I have that feeling. And that's why my sense that this wave is still happening, and that young people are coming along too, making it yet stronger, gave me the strength to keep working. Some time has passed and even now it still carries on,” he told me during our conversation in 2019. It looks like that wave is still on the up.

Boris Mikhailov. Ukrainian Diary

La Maison Européenne de la Photographie (La MEP)

Paris, France

September 7, 2022 – January 15, 2023