Anya Zholud: The Quiet Art of an Unquiet Mind

Portrait of the artist. Courtesy of 11.12 Gallery

In Anya Zholud’s universe, even the most banal object takes on an intense emotional depth. The subjects of her minimalist drawings and sculptures could barely be more mundane: cucumbers, chicken thighs, bags of rubbish, microwaves, office chairs, slippers. Nevertheless, they feel somehow both interesting and important. Zholud’s work is the visual equivalent to the poems of Francis Ponge, the 20th century French “poet of things,” who is most famous for his ode to a bar of soap. In her laconic and lyrical works, everyday objects are used to make statements about what it means to be human. Her series entitled “36 Positions” is a study of a pair of men’s socks which have been discarded on the floor in different ways — or, as the artist explains, “a kind of diary about where a man puts his socks every day in different ways.”

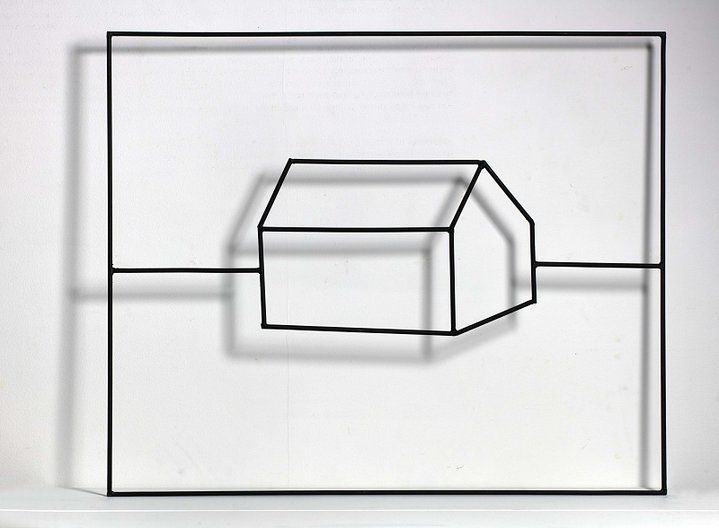

Zholud is perhaps best known for her distinctive metal sculptures. She constructs life-size outlines of different types of furniture and utilities with black metal rods: shelves, desks, dressing tables, electric sockets, stacks of chairs, even houses and graves. By deconstructing and delineating these objects, Zholud draws our eye to what is familiar but overlooked. In 2011, she furnished an empty swimming pool in Kiel, Germany, with metal sculptures in the shape of household objects, recreating the home of a married couple complete with radiator, fan and “his and hers” slippers. Though these works may have a formal perfection, some of her other metal sculptures are deliberately not aesthetically pleasing. Her “Indoor Plants” have cement for soil and bent iron poles for stalks. Her ironically titled “Communication” series features clusters of metal poles descending from the ceiling in the shape of broken telephone wires.

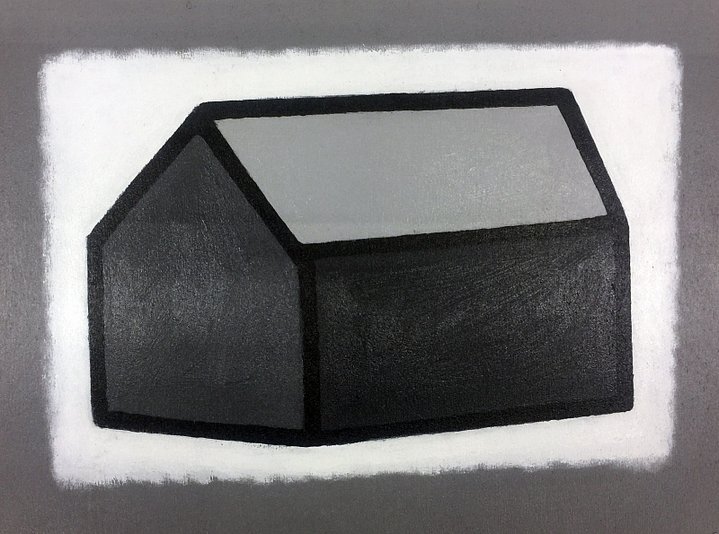

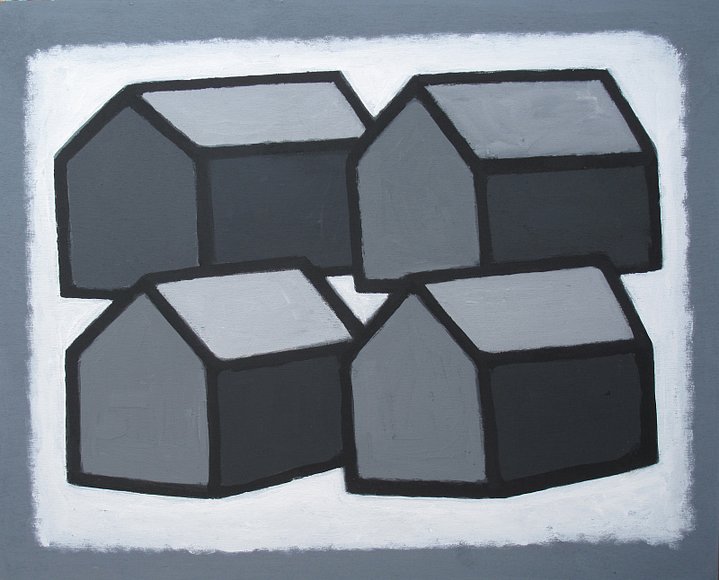

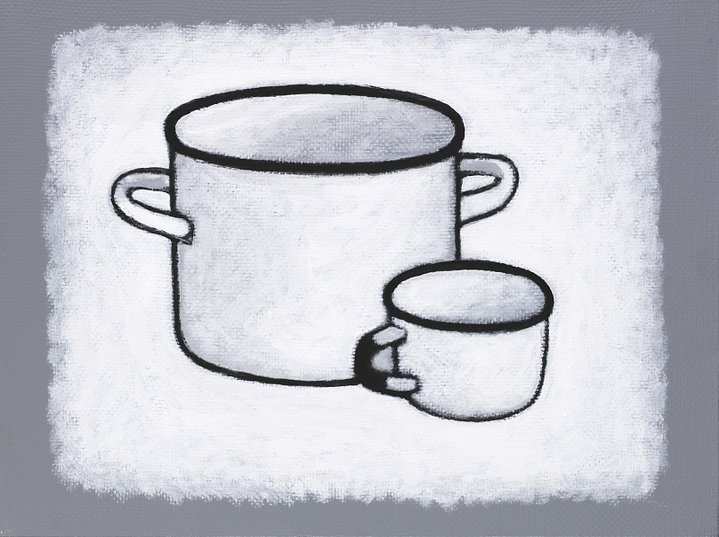

In her paintings, Zholud often works in the traditional genres of still life, landscape and portraiture. However, the works themselves break sharply with tradition. Her still lifes often lack backgrounds, and her portraits are sometimes faceless. She is not concerned with capturing a sense of place or a person’s individuality. Instead, she isolates and focuses on objects and bodies, documenting them in her simple naïve style. She often visibly numbers or dates her works, so that they become a kind of calendar or inventory of everyday life. Still others of her paintings are resolutely abstract. An exhibition at Moscow’s XL Gallery in 2014 exclusively featured abstract works, dizzying black-and-white paintings of spots, stripes and checks. Other paintings depict overlapping amoeboid or box-like shapes in black, grey, green and pink. Many of Zholud’s paintings, like her studies of a male body, lie somewhere in between figuration and abstraction. A sequence of four paintings from her “Bloknot” (Notebook) series depict what could either be a group of chicken wings and thighs or bulbous abstract forms. Some of Zholud’s more colourful compositions are reminiscent of the British Pop aesthetic, such as the boldly outlined portraits of Julian Opie and the neon-coloured minimalist still lifes of Patrick Caulfield and Michael Craig-Martin. Zholud’s work, however, has none of the polish and emotional distance that characterises Opie and Caulfield. Her paintings have a roughness and intensity that is anathema to Pop Art.

Anya Zholud. From the series "Notebook", 2017. Tempera on cardboard. 100x70 cm. Courtesy ART4 museum

Zholud was born in Leningrad in 1981. After graduating from art school in St. Petersburg, she relocated to the Moscow region and now lives in a one-room apartment in the village of Elektroizolyator. Unlike many artists, she does not shy away from reading her own work through the lens of her biography. Instead, she encourages it. One of her exhibitions was simply called: “Museum of Me.” In a recent exhibition at Moscow’s ART4.RU gallery, the wall text was a stream-of-consciousness prose poem about her daily life and tortuous creative process:

“I haven’t left the apartment in two months.

Then I draw the curtains and it’s already winter.

My eyes aren’t used to daylight, my feet aren’t used to walking on the ground, my eyes have lost their peripheral vision.

It’s nothing to do with art.”

Her work never escapes the biographical. In “After the Winter” (2015), a series of monochrome paintings of different types of crockery, there are three canvases that read: “Buy a painting;” “I’m looking for work;” and “I don’t have a bathroom.” She turned her studio-cottage in the village of Arinino into an artist-run space, where she regularly exhibits works by her artist friends from Moscow and St. Petersburg. In a recent display, colourful paintings covered the walls. Outside, one of Zholud’s wrought-metal sculptures, in the shape of a car, stood parked by the shed. Just like in the Soviet apartment exhibitions of the 1980s, there was a blurring between domestic and artistic objects. In one of the cottage’s corners was a large stack of firewood where each individual block was adorned with a little plastic eye, allowing these everyday household objects to assert their voyeuristic presence.

In an exhibition called “Domestic Archaeology” in 2014, there was a group of loosely-painted works depicting tools, vessels and extension cords. On the floor underneath the paintings, the objects themselves lay as though they had fallen out of the paintings. Similarly, it is hard not to fall into Zholud’s works. Her simple paintings and sculptures beckon you into them, seducing with their artifice and yet reminding you of your own reality.