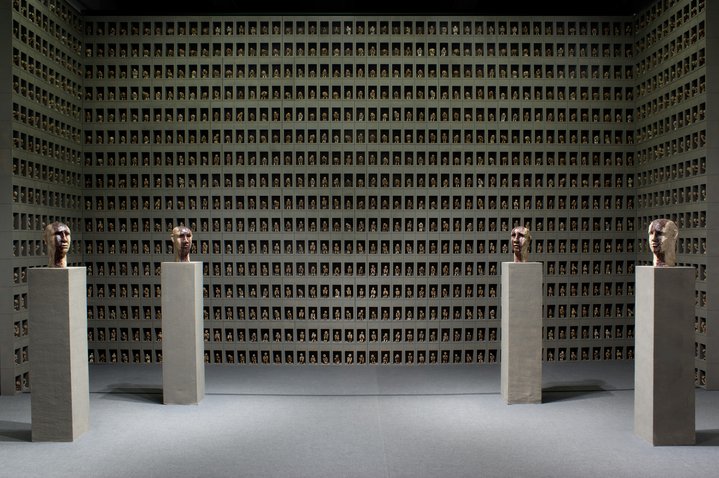

Andrey Kuzkin. Prayers and heroes, 2016–2019. Installation. Courtesy of the artist

Andrey Kuzkin: bread, blood and body

Russian sculptor and performance artist Andrey Kuzkin delivers tragic truths about the human condition through two mediums that are always at hand: his own body and rye bread.

A young man walked in circles in slowly hardening concrete for four hours, until his feet were nearly trapped; or, seated on a gallery floor, he cut the letters “Что это?” (“What is this?”) with a knife on his bare chest... In the late 2000s, Andrey Kuzkin burst onto the Russian art scene with radical performances on a par with the self-destructive endeavours of the Viennese Actionists or Marina Abramovic’s incredible feats of endurance.

Kuzkin was born in Moscow in 1979 and trained as a graphic designer. The son of the late painter, Alexander Kuzkin (1950-1983), Kuzkin-junior has referred to his father and the trauma of his early loss in several works, including an on-going series of performances called ‘Natural phenomena’. In it, he literally turns upside down the traditional perspective of a human being looking down on the nature surrounding him by reducing himself to a mere part of it. “A man is like a tree and a tree is like a man”, is how the artist himself puts it. It is a homage to his father’s work ‘99 landscapes with a tree’. Stark naked, the artist poses as a surreal tree, with his legs and hands pointing upwards like branches while his is head buried in the ground. Kuzkin is determined to repeat this performance in different parts of the world 99 times. By now, the count has only reached 40. Locations vary from deserted fields and woods to central streets of New York and London, where he was once arrested for indecent exposure. Simple, visually provocative and physically demanding, this typical Kuzkin work reflects fascination with the unbound primeval forces of nature and the unfathomed depth of human suffering.

In 2011, he put all his earthly possessions, including artworks, underwear and his Russian passport into 58 metal boxes and then welded them tight in front of astonished gallery visitors, announcing that these boxes should remained sealed for 29 years. The work was called ‘Everything is ahead!’. The desire to start from scratch, expressed in this striking act of renunciation, is also characteristic of Kuzkin, whose artistic practice oscillates between yearning for publicity and a desire for obscurity. After staging a solo exhibition at the Moscow Museum of Modern art, which included documentation of over 70 performances and won him the 2016 Kandinsky prize, Russia’s most prestigious private art award, he suddenly got “tired of exhibitions” and focused on secretive performances in the woods. Only a few close friends were allowed to attend them. However, Kuzkin keeps carefully documenting them for posterity. “I am addressing the people of the future. I hope that something I’ve done will survive me,” he once told me in an interview.

Ironically, his media of choice are anything but durable. Performance, the most fleeting of arts, can only survive through documentation. His other favourite medium is bread, a material of strong symbolic value (consider the sacrament of the Eucharist) but questionable longevity. “This symbolism is especially relevant in Russia where bread and salt were regarded as sacrificial offerings since pre-Christian times. It is something that is unlikely to work anywhere else,” he said. Indeed, for an older generation of Russians throwing away bread was a major, almost sacrilegious offence. There’s a grimmer side to the symbol, as well. Prisoners in Russian jails have traditionally been making small figurines of people out of bread, which are sold as souvenirs. This connection is crucial for Kuzkin. “The body is but a prison for the soul,” he thinks. Once, he spent a week making bread sculptures together with prisoners at a Krasnoyarsk jail, in the heart of Siberia. (The project was a part of the Krasnoyarsk biennale.)

In Kuzkin’s hands, soft rye bread becomes as a harsh as raw wood. Bread-and-salt pulp which he uses for his sculptures is a tricky material to handle. When it dries, its surface gets rough, often crackled and dark. It cannot represent the beauty and harmony of the human body, but can perfectly simulate tortured, distorted human flesh. To avoid these bread figures eventually becoming mouldy, Kuzkin adds another very traditional Russian ingredient, Vodka, to the mixture.

Three larger-than-life bread sculptures called ‘Heroes of Levitation’ were exhibited during the 2011 Venice biennale as a part of an exhibition called ‘Modernikon’. However, Kuzkin, dissatisfied with the “commercialization” of his preferred medium, once brought bread bas-reliefs of 100-dollar notes instead of the human figurines, popular with the collectors, to Moscow’s Open Gallery, which represented him at the time. (The astonished gallery owner, Natalia Tamruchi, paid for the works in actual dollars. Kuzkin later proclaimed this exchange was a perfomance, called ‘Money for Bread’).

Yet, he has never abandoned the technique he liked so well. In 2019, he unveiled an installation consisting of over 1,000 bread figurines of naked supplicants, praying on their knees. It took over two years to finish. Complemented by four life-sized human heads on which the artist’s own blood had been spattered the project was conceived as a homage to Russia’s the tragic history. Yet, it can also be viewed as an eerie, but compassionate, portrait of mankind in general. Shown for the first time at the Moscow Biennale in 2019, it will be displayed again during the Garage Triennial, which was once scheduled to open in June, but has been postponed because of the coronavirus epidemic. In the meantime, Kuzkin’s magnum opus acquires new connotations. The work, called ‘Prayers and Heroes’ consists of three walls filled with numerous figurines, each one painfully alone and isolated in its own box. For sure, it will strike its post-epidemic audience as a poignant metaphor of the world in lockdown. The artist was going to open a big exhibition called ‘Deliverance’, which would have included this work, as well as smaller bread sculptures. These plans were shattered by the coronavirus crisis. “I wanted to stage it in a big excavated hole in the ground and invite visitors down there,” he explains. “After the exhibition was finished, I wanted the hole to be filled with soil, covered with asphalt and turned into a parking lot. Because history, however tragic it may be, is something we have to finally leave behind, if we want to live.”

The project sounds gloomy, yet the message behind it is surprisingly hopeful!