Andrei Ribakov and the Many Faces of Russian Power

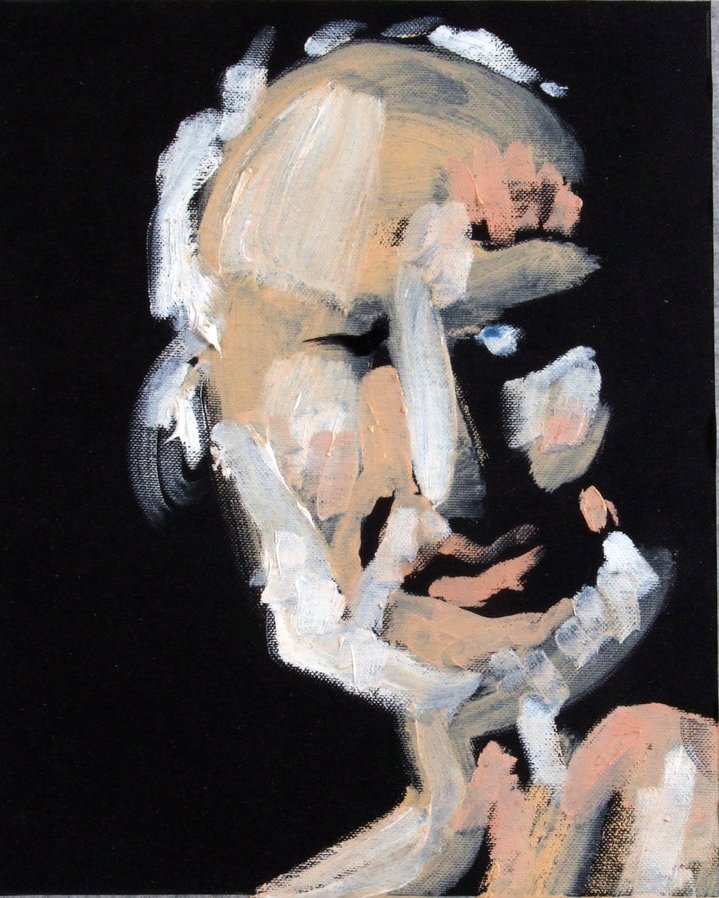

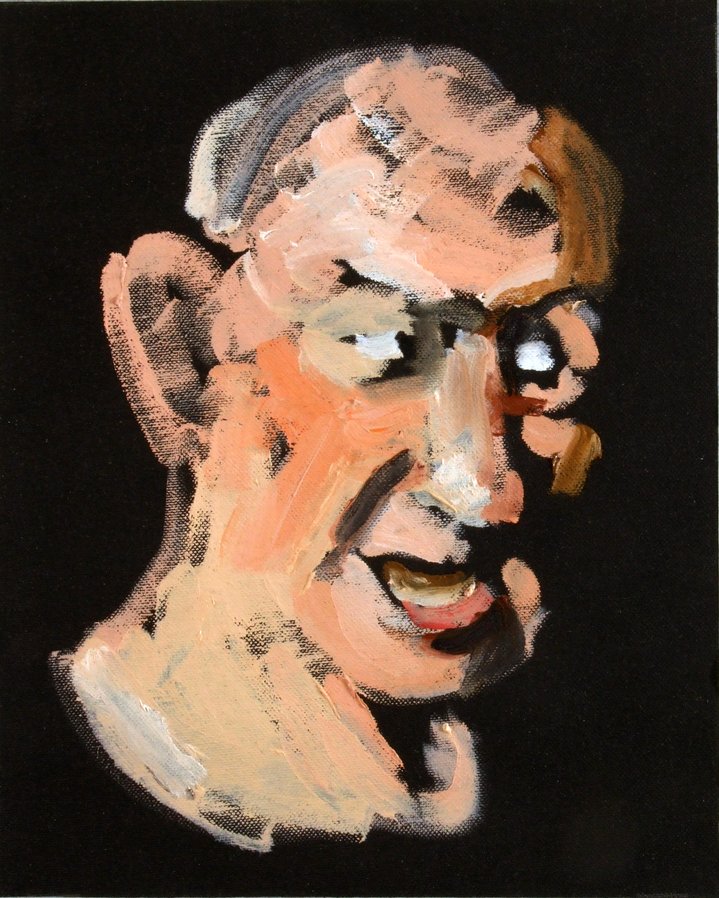

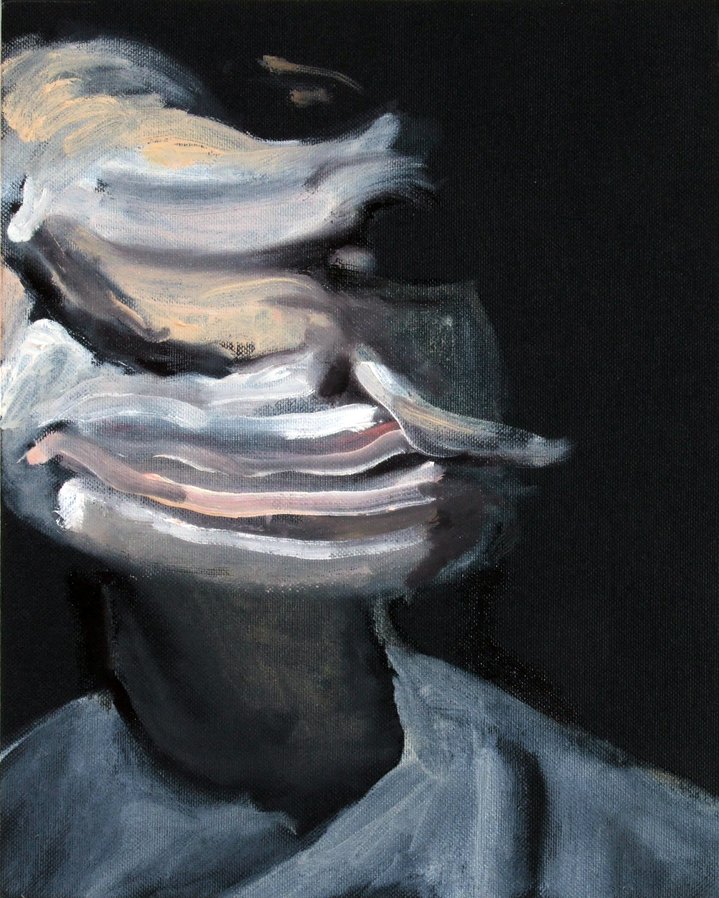

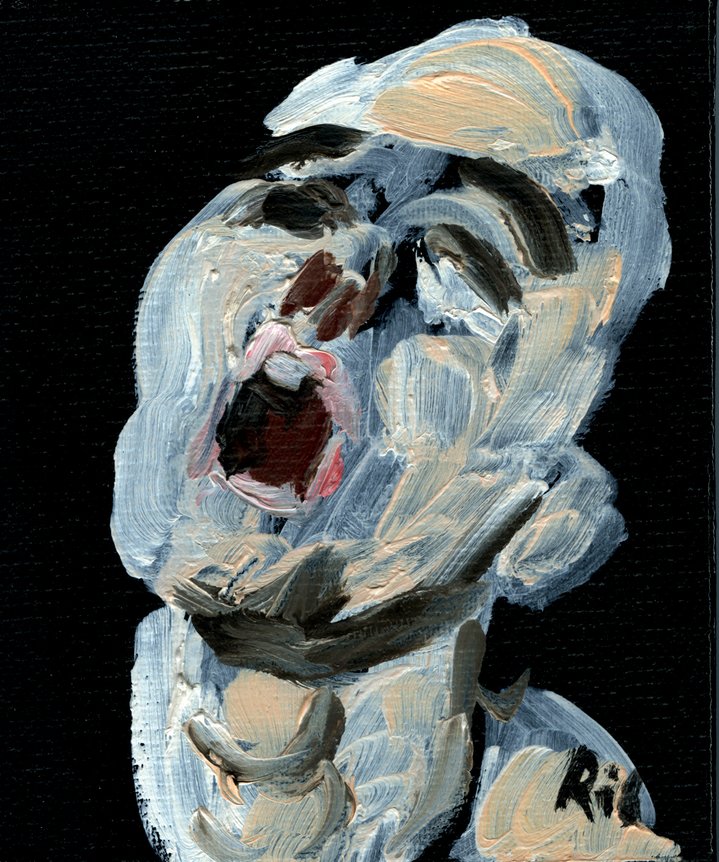

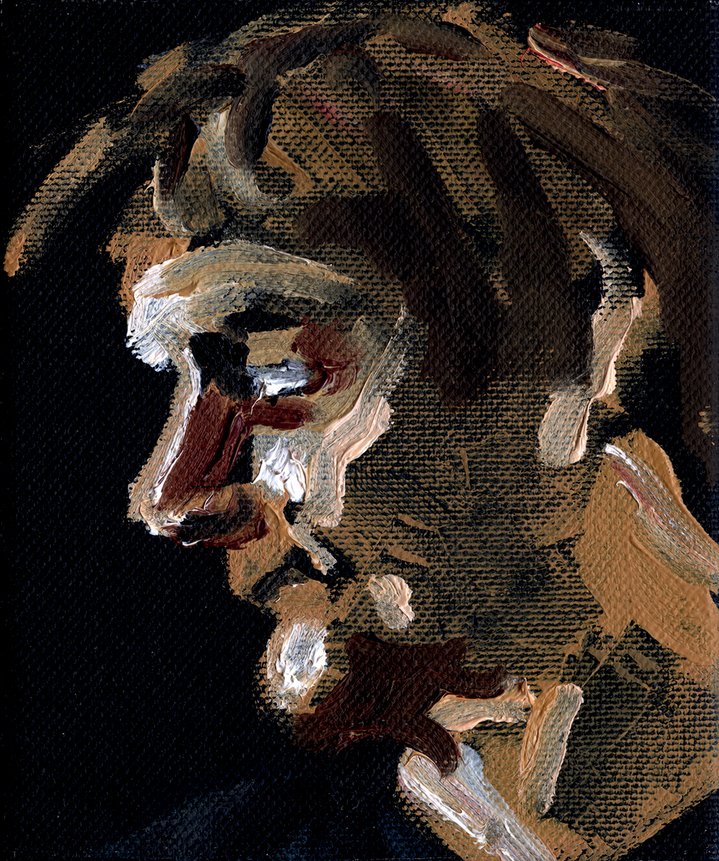

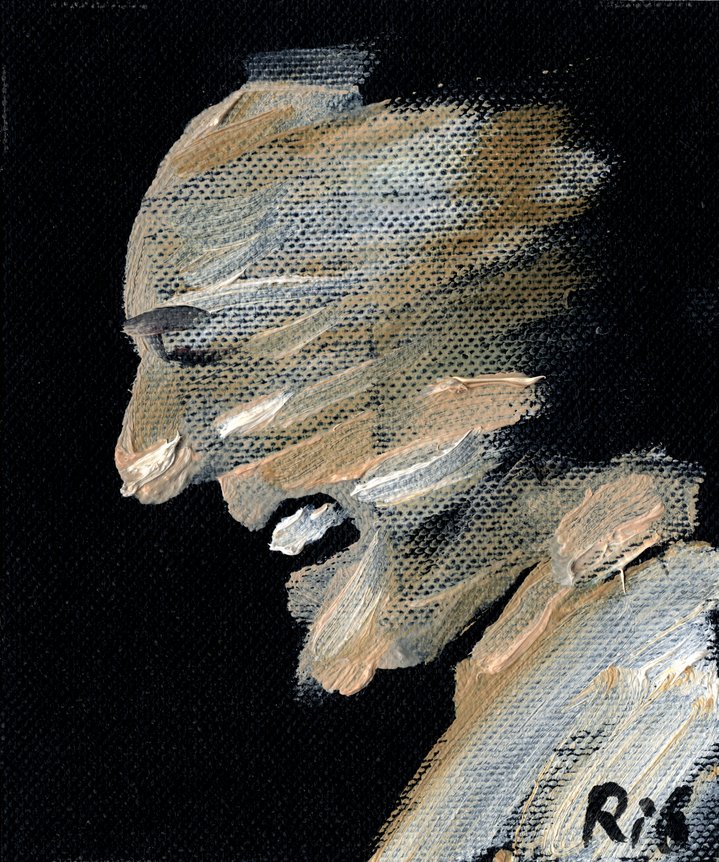

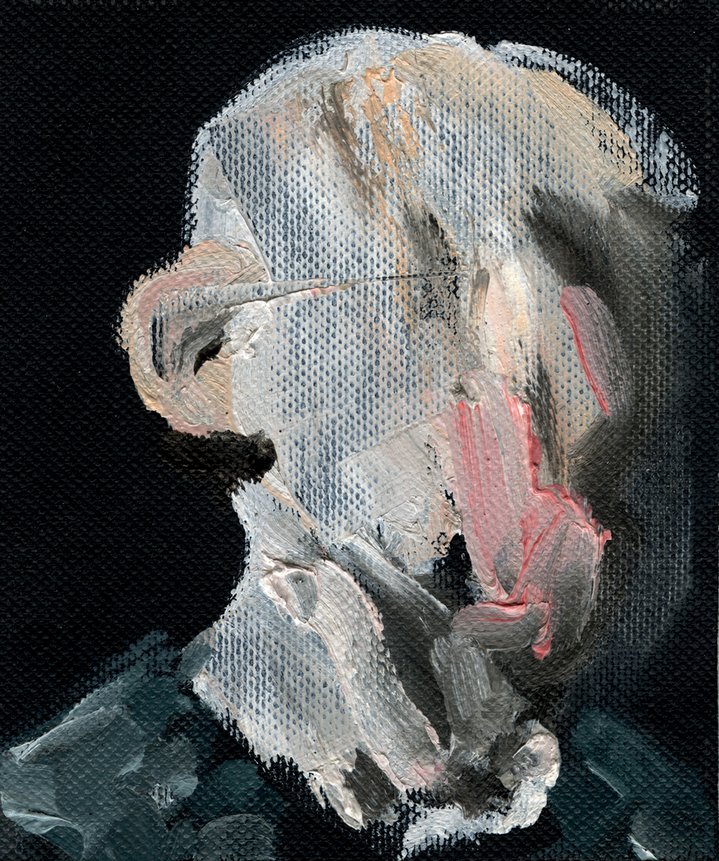

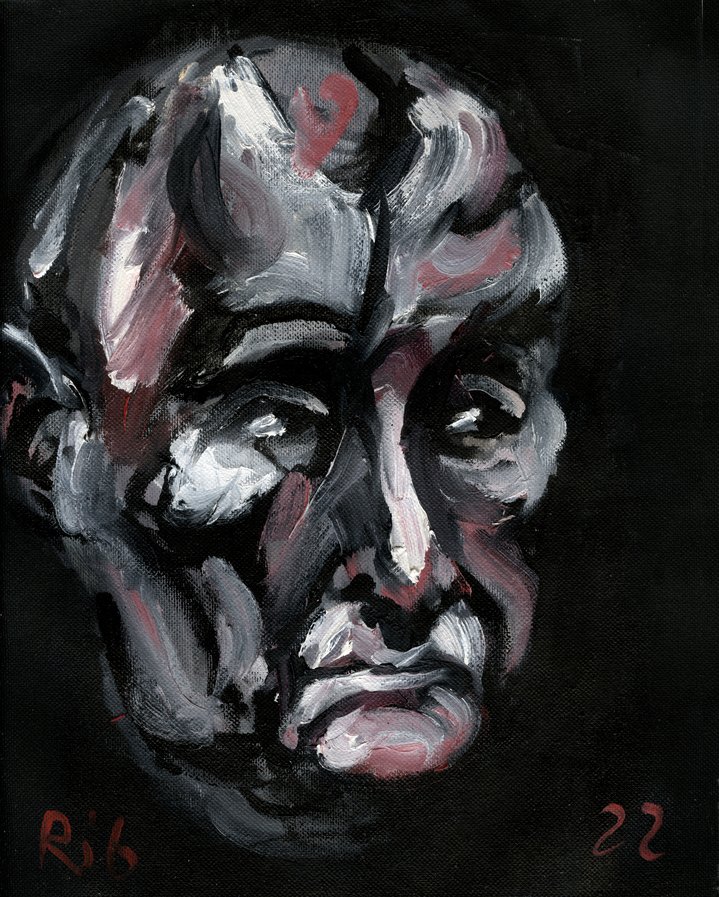

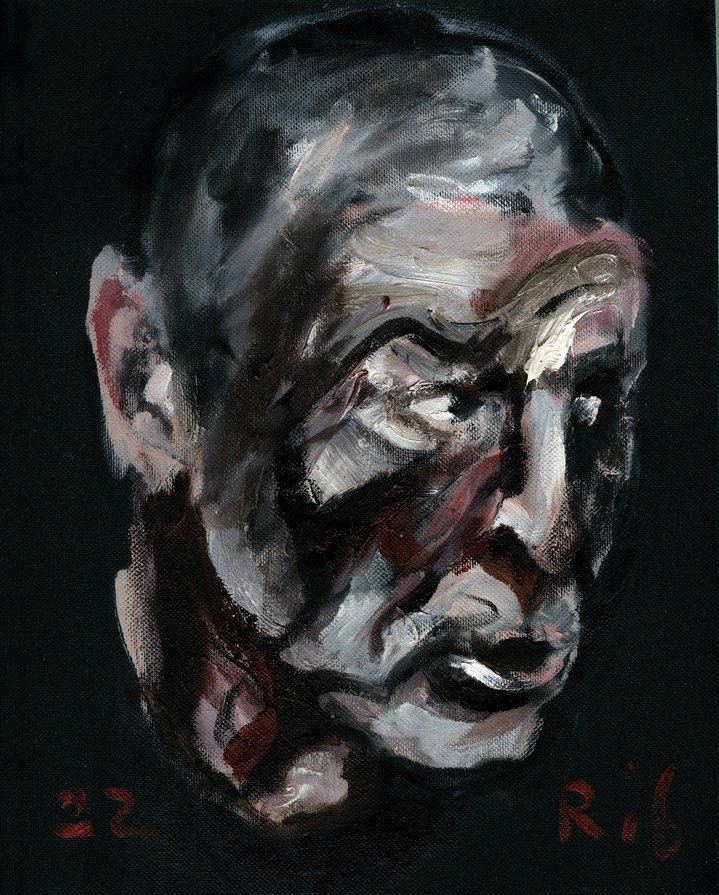

Andrei Ribakov. From My Contemporaries series. Courtesy of the artist

When some years ago Moscow artist Andrei Ribakov decided to paint his friends and acquaintances in the style of Francis Bacon, he did not expect it to evolve into an unflattering collective portrait of the Russian elite.

Where do artists find their inspiration? Andrei Ribakov’s (b. 1963) convoluted artistic career proves it can be in the most unlikely of places. He has transformed charred firewood and wine bottles into sculptures and witnessed the face of history in the frowning looks of panic-stricken government officials on TV news. A painter and a graduate of Moscow’s State Polygraphic Institute, Ribakov has been creating text-based art for many years. He has co-authored works with poet Vladimir Vishnevsky, incorporating the poet’s one-liners into his own paintings and collages. And like the archetypal 21st century artist, he has experimented in a wealth of other media.

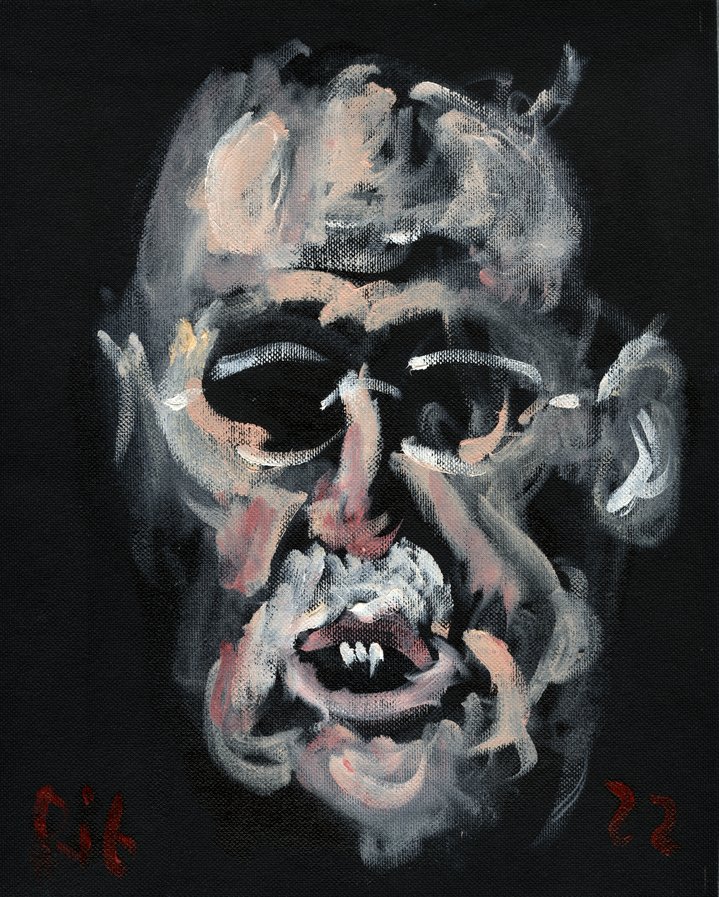

Once, he created a series of sculptures out of opaque Italian glass wine bottles, turning them into metaphorical images of human body. During the pandemic, he left Moscow with its strict quarantine limitations and high mortality, finding sanctuary in his dacha. Chopping wood for his stove, he thought about making sculptures from materials he had in his immediate environment: logs and nails. To add colour and drama he charred the logs in the stove. “It’s a collaboration with fire”, as he puts it. Each artwork went in and out of the fire numerous times. The laconic, totemic objects which emerged from the flames bring to mind ancient traditions of Central African art. The artist called his series ‘Burned in the Pandemic’’; it became a tribute to friends who died from the coronavirus. In another series, ‘Thirty emotional portraits of my contemporaries’ he created a distinctive take on the portrait genre. For this project, Ribakov’s models were his friends. In these expressive, farcical depictions of faces on a uniform black background, each of his subjects, disengaged from their social and psychological selves, becomes an embodiment of human emotion. “My goal was to capture movement and feeling”, he explains. “Many of them are depicted shouting, with their mouths wide open, which is why they remind people of Francis Bacon who often painted open-mouthed models, but his technique was totally different and there are influences of other artists as well.”

On 21st of February 2022, three days before Russian troops entered Ukraine, a meeting of Russia’s Safety Council was held at the Kremlin. Top-level government officials assembled to recognize the independence of Luhansk and Donetsk People’s Republics, two regions in the East of Ukraine bordering with Russia. Each one delivered a short speech on the subject. The fighting was about to begin and judging by the terrified looks of their faces, the bureaucrats knew. The event was broadcast by several Russian state-owned TV channels. “For some reason, I felt that it was an important historical event that would lead to something”, Ribakov reflects. He watched the news live on his computer and started making one screenshot after another. Then he painted them in the same style he had used in his recent ‘Emotional portraits’ series, depicting each bureaucrat in several different versions. Gradually, a collective portrait of Russian power emerged.

Ribakov cites Ilya Repin’s (1844-1930) epic painting ‘Festive Seating of the State Council on 7 May 1901’ as one of his sources of inspiration. “I considered painting them all onto one single, large canvas, like Repin did”, he recalls, “Yet, many people think Repin’s sketches for this work are more interesting than the final painting”. The effect of Ribakov’s portraits, displayed together as a one big panel, is uncanny. The images look monstrous and yet are oddly accurate in their facial features and expressions. The series could be an illustration to a modern-day catechism of deadly and not-so-deadly sins. The faces show different shades of fear, greed, servility, and cruelty, the full spectrum of human faults and passions. But, in this haunting ‘Safety Council’ series, the causes of this transformation run deeper than the painter’s own artistic whims: it is the corrupting influence of power that distorts the faces and corrugates their souls. The project is a silent, yet merciless verdict on those at the helm of Russian society. There is no hope left for them, and even sinking into the total blackness of oblivion seems impossible, a sentence which anyway seems mild.