Andrei Mitenyov: the chronicles of a Russian prison

The Moscow artist, who was sentenced to a jail term, has created a graphic saga about the grim underworld of Russian penal institutions.

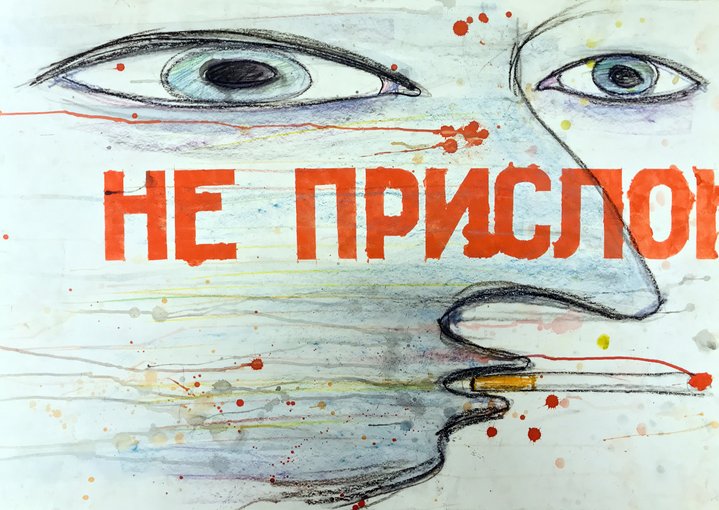

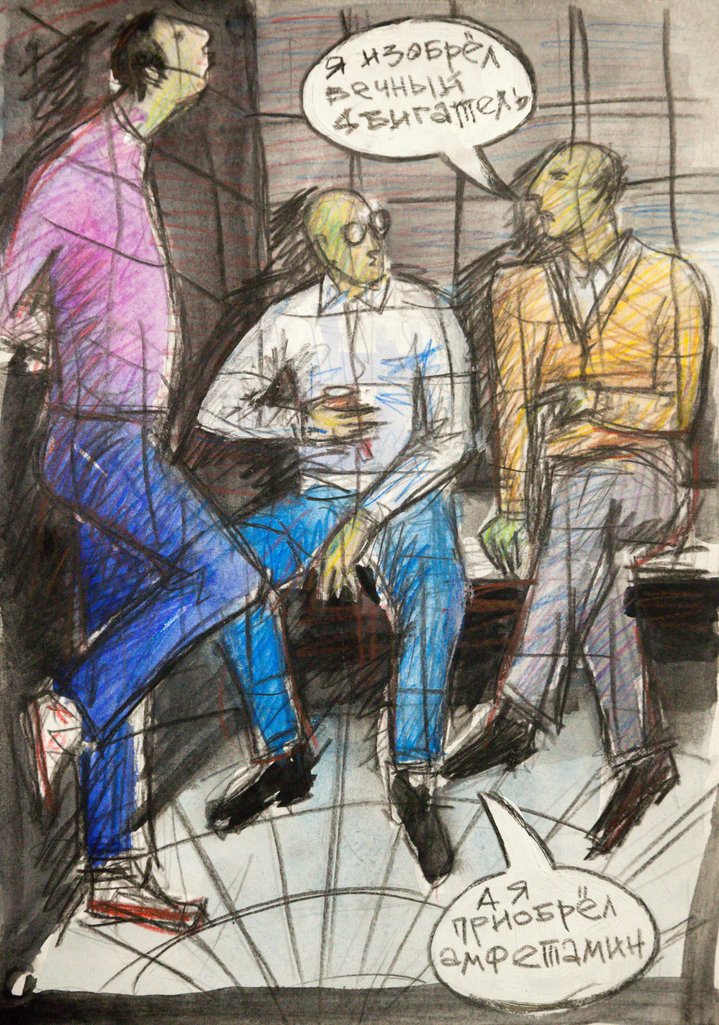

If there’s one artist residency you would not want to apply to, it’s the one that Andrei Mitenyov (b. 1974) now has on his CV. The Moscow sculptor, whose works adorn the squares and parks of several Russian cities, was a well-known figure of the capital’s art scene. He had turned his studio, hidden in a basement of an old building in the centre of Moscow, into an artist-run space called ‘Это не здесь’ (“It’s not here”), a hub for underground concerts and exhibitions. All that changed abruptly three years ago, when Mitenyov was arrested for the alleged purchase and possession of illicit drugs and subsequently sentenced to two and a half years in jail. (His case was a typical one, rather than a tragic exception: over 70,000 recreational drug users were incarcerated in Russia that same year).

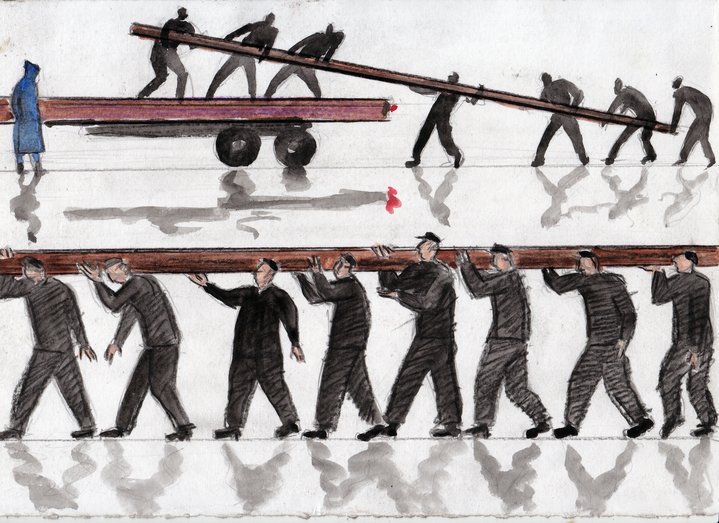

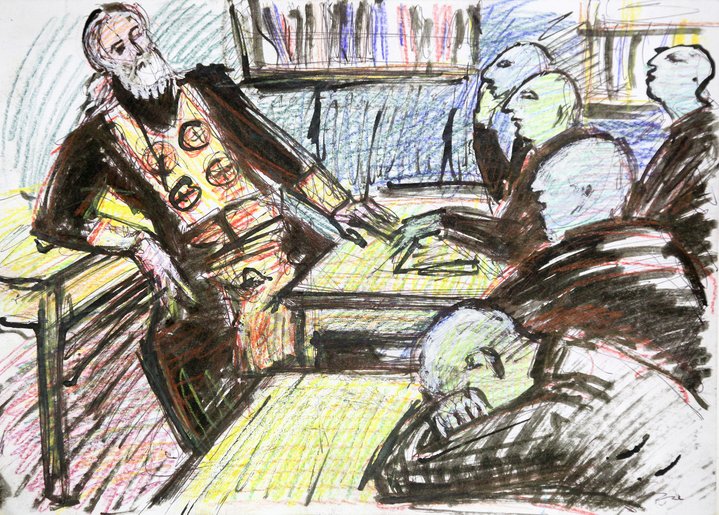

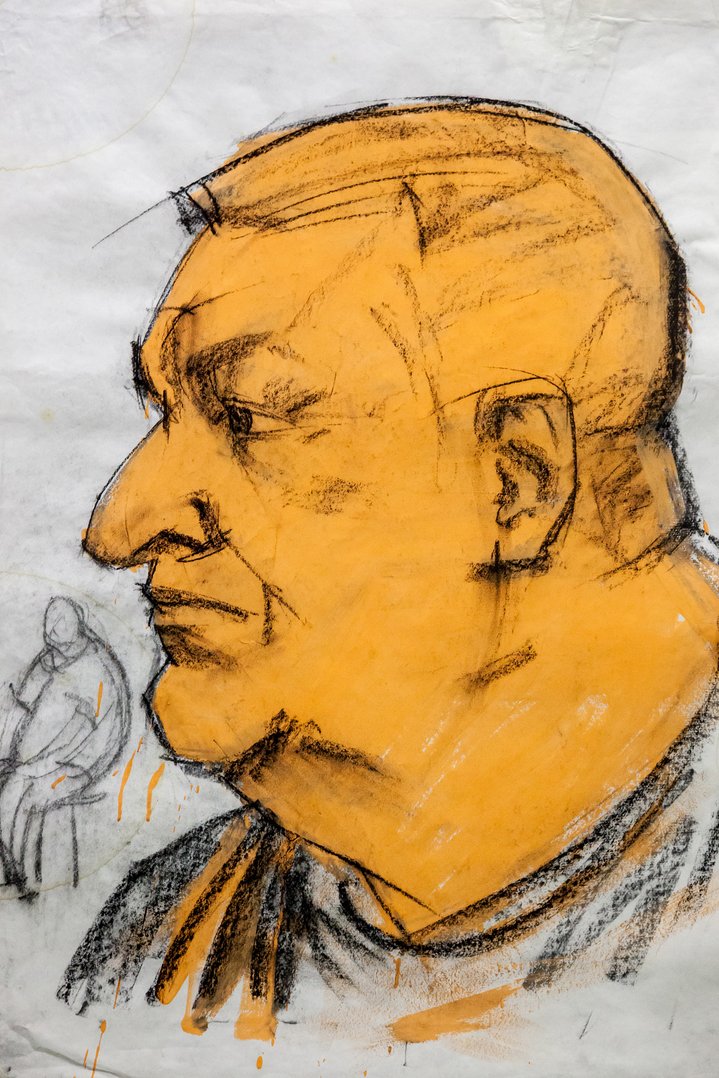

However, Mitenyov found his own way to keep up his spirits. He managed to obtain coloured pencils and paper and started sketching everything he saw around him. “In prison, I did not feel involved in what was happening. I was like a researcher, observing the astonishing life of this bizarre place,” the artist recollects.

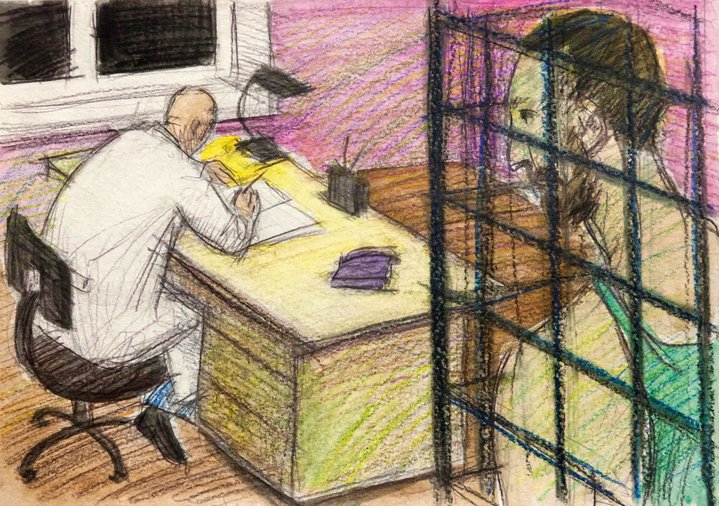

According to Mitenyov, his drawings have not only artistic, but also documentary value. Photography and filming are not allowed inside Russian prisons, so for those lucky enough to never have set foot there, those drawings might be the only chance to look behind prison bars.

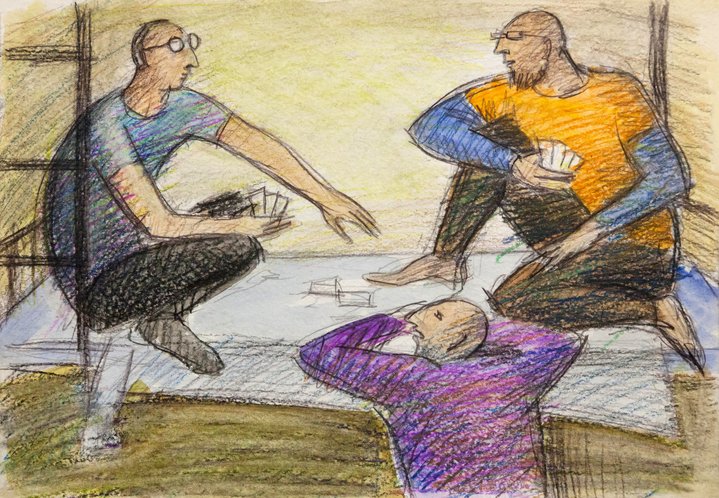

His subject-matters may seem harmless. There are no depictions of violence or abuse of power. Yet, the wardens were suspicious of his artistic mission. He received many threats for drawing activities that are officially forbidden, but unofficially tolerated by the guards, such as smoking or brewing ‘braga’, an alcoholic drink. The wardens confiscated his sketches on various pretexts. After his release, it took Mitenyov and his relatives over two months to retrieve them. About a quarter of his works disappeared for good, but the artist re-created them again from scratch. His fellow inmates, on the other hand, were curious and encouraged him to continue. Some even threatened to use physical violence if he didn’t.

Mitenyov takes the viewer on a tour of different Russian penal institutions: from a pretrial detention centre in Moscow to a provincial correctional facility. His series resemble a graphic novel or a comic book: each drawing is supplemented by a short story. It records the other inmates coming and going, as well and the changes in the artist’s own fortune. On one occasion, he is punished by being sent to the kitchen block and assigned the job of sorting tons of rotting cabbages. Another time, the wardens recognized his artistic abilities and gave him the job of putting together the institution’s stengazeta (a hand-made wall-newspaper).

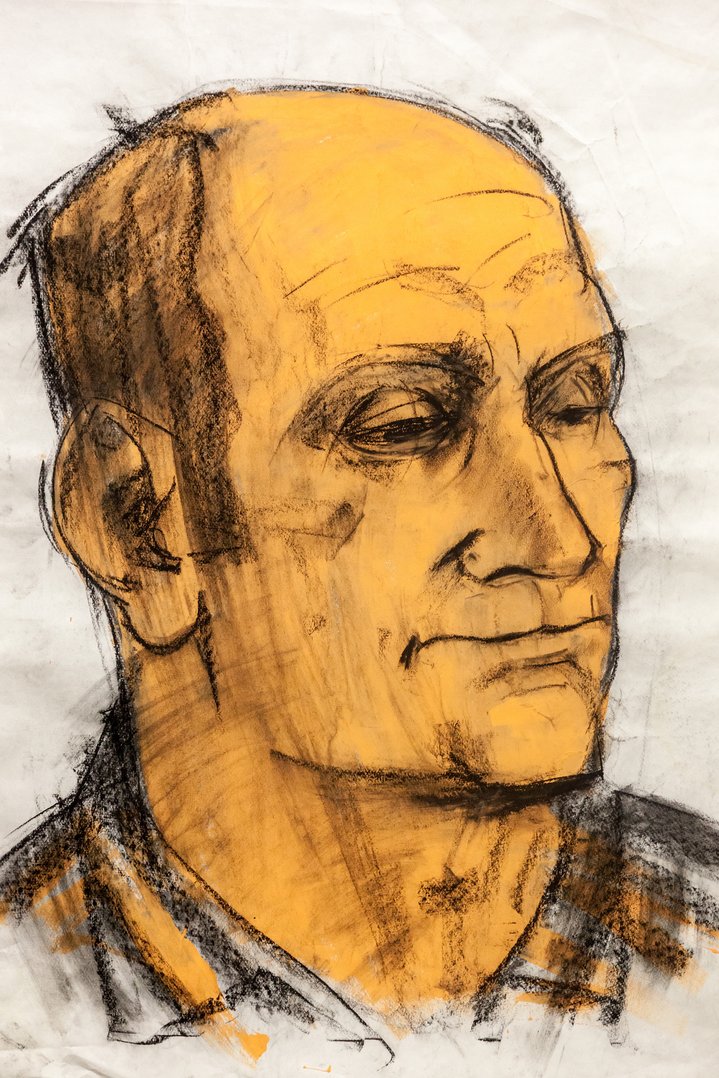

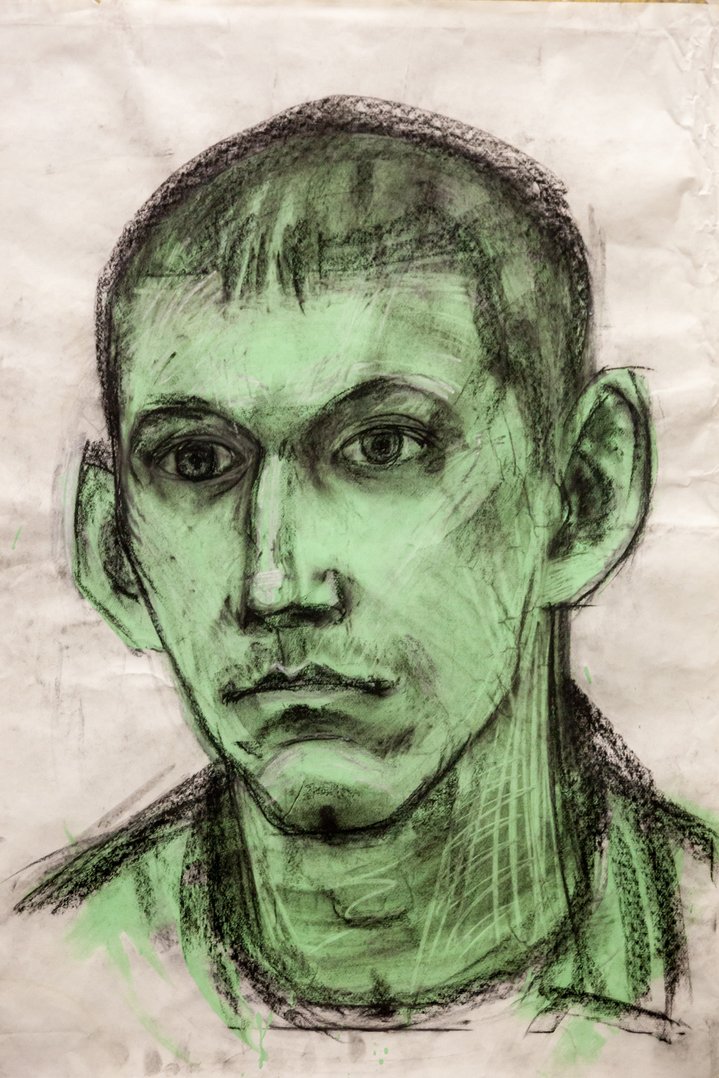

In two and a half years, Mitenyov produced over 250 graphic and painted works during his imprisonment. They fall into six sections, varying in subject-matter and even in style. Sometimes, he sheds light on the absurd daily routine of prison life. At other times, he focuses on the personalities of other inmates or his own psychological changes.

“I was studying the prison's inhabitants with anthropological interest, first and foremost myself,” he says. For him, jail was a “powerful spiritual experience” and he carefully documents his own passage all the way from the depths of despair to the catharsis of repentance and, ultimately, to a quiet acceptance of his fate.

He portrayed his fellow inmates and interviewed them about their notion of freedom. Shortly before his release, he started to document his own dreams. At that time, he was allowed to paint in acrylic, using old bedsheet as canvas. This latest series, ‘Prison Dreams’, which is both surreal and colourful, feels like an attempt to flee from reality into the realms of his own fantasies. Whatever he sees, be it his own visions, the faces of other convicts or ugly daily routines of prison life, he looks at it all with a strangely benevolent, forgiving eye. The name he chose to give to the whole body of his prison works, ‘Deus Caritas Est’, is in fact derived from the favourite motto of Russian convicts. According to Mitenyov, the most frequent graffiti he saw scribbled on prison walls during his journey was “Бог есть любовь”. It translates as “God Is Love”.