Alexander Povzner’s Circles of Paradise

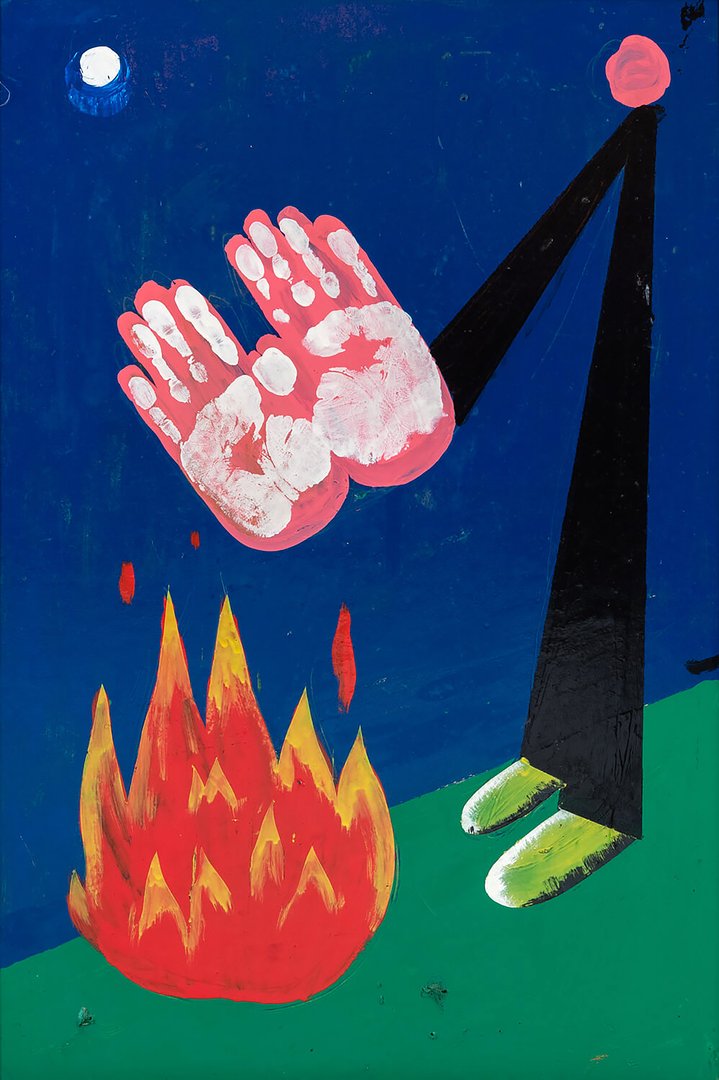

Alexander Povzner. 'Berlimbo' project, 2022–2023. Courtesy of the artist

Berlimbo is an exhibition evoking Alexander Povzner’s experiences as a new immigrant in Germany, one of the many Russian artists who flocked there in 2022.

Alexander Povzner (b. 1976) is a Russian sculptor, painter and graphic artist. Son of the artist Lev Povzner (b. 1939), he studied sculpture at the Russian Academy of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture, then at the Surikov Institute in Moscow. These are strongholds of the traditional visual arts meaning craftsmanship, its goal to provide skills to accurately depict the visible. After a decade-long break he went back to study, this time at the Institute of Contemporary Art Problems, now the ICA, where the focus was on conceptual art. Now in the middle of a successful career, he has been actively exhibiting since 2007, collaborating for over a decade with the XL Gallery in Moscow.

Povzner exhibited most recently at XL in Spring of 2022, just after the conflict in the Ukraine began (in Russia you must call it a ‘special military operation’ and if not, you can be fined, arrested or imprisoned). Povzner left the country, along with many artists and professionals from the Russian contemporary art scene with no idea of what would happen next.

Berlimbo opened in late January in Spandau, a remote district in Berlin, once a town with an elaborate defense complex, called the Citadel. It’s a fitting place for the title of the project and its worldview: a fusion of the words Berlin and Limbo, where the city is seen as a kind of hell, and the artist's existence in it as an infernal periphery, an obligation to coil Kafkaesque circles among other souls who have not sinned, but for various reasons are not worthy of the light.

Povzner’s exhibition is about people who have been launched into an airless orbit from their formerly comfortable lives, just like him. They are of different nationalities with passports of different colours. They find themselves in Berlin (not the worst city on Earth) a place everyone used to love to go to: strolling through the galleries and museums, walking in the Tiergarten, going to techno clubs. But it’s a different story to be a forced migrant here. Since the outbreak of the Russian-Ukrainian conflict, the city has become the largest transfer and sorting point for refugees in Germany. It has exacerbated the housing problem brewing here since the mid-tens. However here artists crucially get a self-employment visa which entitles them to work. You have to run through all the cultural institutions you know and collect letters of intent, which state, for example, that such and such a gallery would like to work with the artist and that the artist’s presence in Germany is beneficial.

You get a slot at the relevant institution and submit your documents. Tourist visas expire rapidly, the money runs out, but you cannot leave because then you would have to start all over again. And from where? Not everyone can return to apply at the same place of registration.

This mad dash through the floors of the bureaucratic machine comes with general unsettlement, couch surfing with acquaintances, looking for residences and studios. The tickertape in your head goes like this: "Nothing to moan about … plenty of people much worse off … it's a good option". Yet being in limbo is a life without light, there is nothing good about it. It is how to survive in a situation of constant psychological pressure.

Povzner resonates keenly with his environment like a tuning fork. His characteristic modus operandi is to pick up strangeness, irrelevance, alienation, and reflect on them. In Berlin this alienation overwhelms him. We meet in his studio, a room in a former factory. It's close to the centre, but the bus stop is hidden under a bridge, and the feeling of ‘no-place’ overwhelms me. Alexander compares Gottlieb-Dunkel-Strasse to the peripheral Moscow district of Konkovo where he had (or still has) a studio; it’s an exaggeration.

As we wait for our buses to take us in separate directions, he reflects on the fact that there are few places in cities where homeless people can find shelter: bridges are a godsend. It is the down and outs we hardly notice who are screaming into existence in Povzner's latest works. Hence a recurrent motif, of hats with some coins in front of beggars near supermarkets and in underground passages, an image in his installation and on the exhibition poster. Battered, threadbare hats and a couple of coins made into smiling faces.

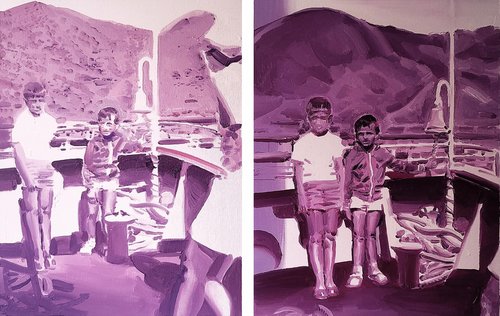

Rags and newspapers are now Povzner the sculptor’s preferred medium. From them he assembles the symbol of democratic food of the German capital, the swollen cones of the döner kebab. The Gotisches Haus shows a second part of the exhibition he made in the summer in a residency in the town of Neuwied planned before the hostilities. People stripped of volume and their own content, reduced to a role of paper sheets, flapping in the wind, strung up on a clothesline. That artistic statement, part of the group project Das Dach (The Roof) is about displaced artists which Povzner calls "his Guernica". Now he elaborates on this theme: a man is pinned on a huge receipt spike, stapled together with other papers, and sealed with sellotape. The man is crucified on these paper folders.

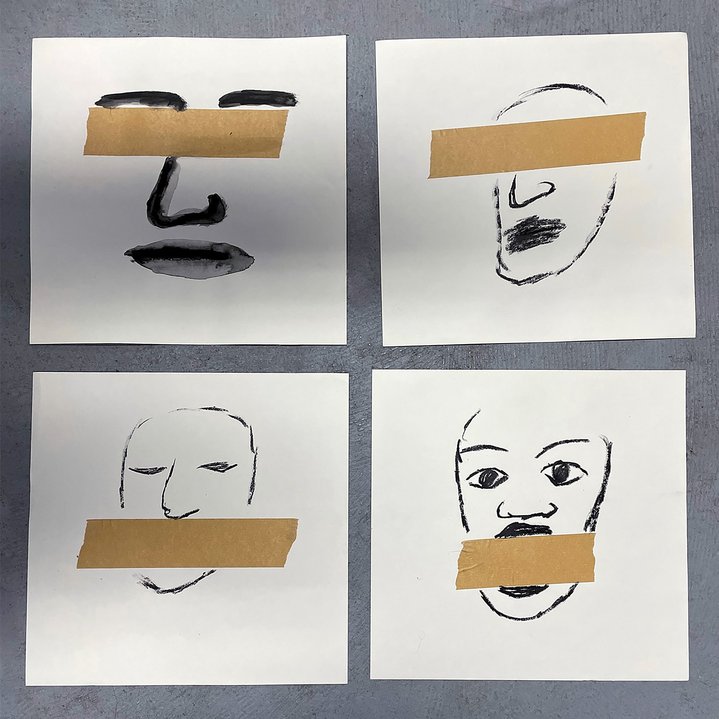

The Spandau exhibition is the result of four months’ work in Berlin. From the beginning, Povzner made it a rule for himself to draw every day, irrespective of what was going on. A large portion of the material in the show is graphic sheets in various series. People with erased faces and words in German, taken out of context, either intelligible or guessed at. He himself says of this: "What I see, I draw." Not knowing German, he translates scraps of text with an automatic translator back and forth until they become like smooth river pebbles. And then there are people squeezed literally into the shelves between books. People like pickles in a jar. People who are hot dogs, disposable, dehumanized. Of whom, at best, only a paper trail with a stamp remains - that's if you are lucky.

A sense of alienation is what accompanies the celebrated and successful artist Alexander Povzner in his daily jog through grey, winter Berlin. Many people are or could be in a worse place than him. Such a life is the consequence of the forced emigration of a person who no longer accepts his country or is not accepted by it. There is nothing to envy here.