Alexander Mareev, the sphinx of Russian contemporary art

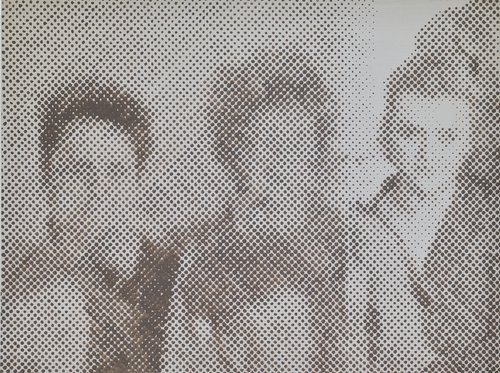

Artist Alexander Mareev. Courtesy of Krokin gallery

A mysterious Russian artist oscillating between realism and conceptual art has returned to the art scene after two decades. His solo exhibition called ‘Communism and Buddhism’ is now on view at the Krokin gallery in Moscow.

Alexander Mareev (Lim) (b. 1969) belongs to a generation whose artistic coming-of-age coincided with the collapse of the Communist regime. Back then, the transition from the semi-underground existence of Perestroika to the wild bohemian lifestyle of the 1990s proved to be too abrupt for many artists. Some, like Sven Gundlakh (1959–2020) completely lost interest in art, some passed away because of drug or alcohol abuse, or resorted to criminal violence. Mareev did not die, he just disappeared.

He used to share a studio with the notorious iconoclast Avdey Ter-Oganyan (b. 1961), and he hung out with the Inspection Medical Hermeneutics group which included Pavel Pepperstein (b. 1966), Sergei Anufriev (b. 1964) and others and where he was assigned the rank of Junior Inspector. He was a member of Arkady Nasonov’s (b. 1959) ‘Cloud Commission’, another similar art group of the time whose members were officially assigned to watch different types of clouds. He had his first solo show in 1992 at the now defunct L Gallery, then one of the Moscow’s important hotspots for contemporary art. He was invited to exhibit his works at the MAK museum in Vienna alongside Ilya Kabakov. (b. 1933) and Viktor Pivovarov (b. 1937); his works were included in the permanent collections of the State Tretyakov Gallery and the NCCA (the National Centre for Contemporary Art which is now a branch of State Pushkin Museum) in Moscow. His photographs from that time show a real bohemian, posing in a hat. Yet, one day he suddenly stopped showing up at openings and parties. He stopped answering the phone. And after his 1998 exhibition, ‘The Blue Cat’ at the Krokin gallery in Moscow nothing was heard from him for over twenty years. ‘Once in a while I tried to call all the telephone numbers I ever had for him, but with no success. The numbers were active, but he never answered’, his longtime dealer Mikhail Krokin told me. Despite this, Mareev was never forgotten, his works continued to be exhibited in group shows and they came up for sale at auction from time to time.

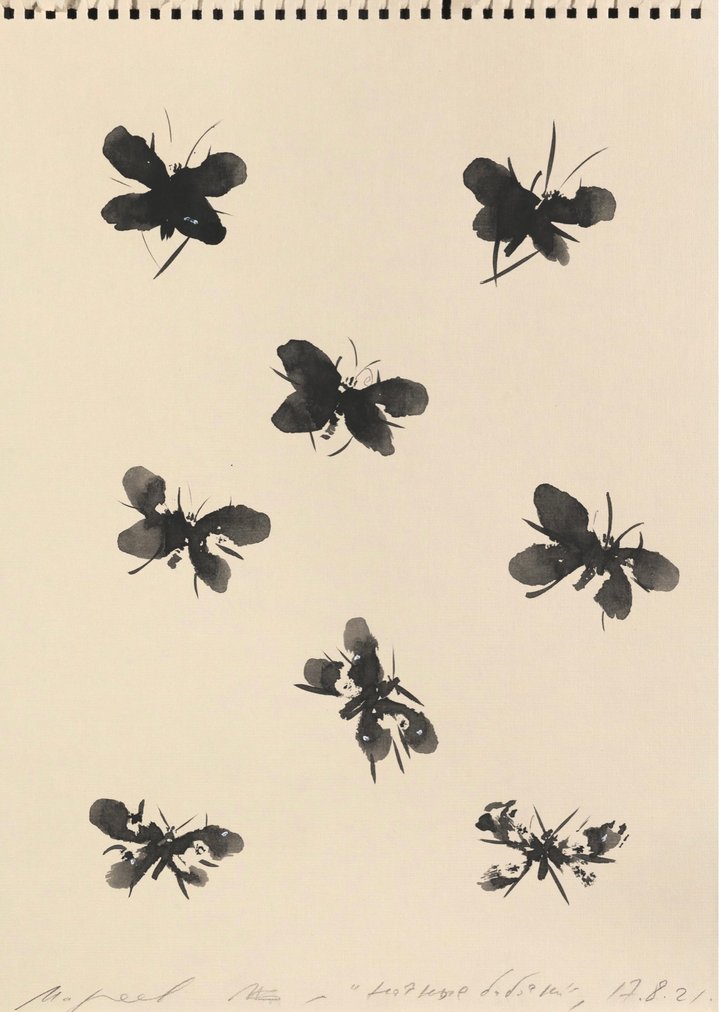

And he did not stop making art. He divided his time between a flat in Biryulyovo a rather sleepy and drab district of Moscow and a small dacha in Donskie Izbischi village in the Lipetsk region, 400 kilometers to the south of the capital. He would make sketches ‘en plein air’ in the summer and sketched standing at the window of his Moscow flat in winter. He put on over a dozen solo exhibitions in an abandoned village library every summer and taught local children how to draw butterflies without catching them. After his sudden comeback last year, the butterfly turned out to be a recurring theme in his art, omnipresent in his first exhibition, ‘The Ray of the Moon’ which took place at the Krokin gallery. He paints them in monochrome and seems more interested in their shape and the way they flutter, than by the colourful patterns on their wings

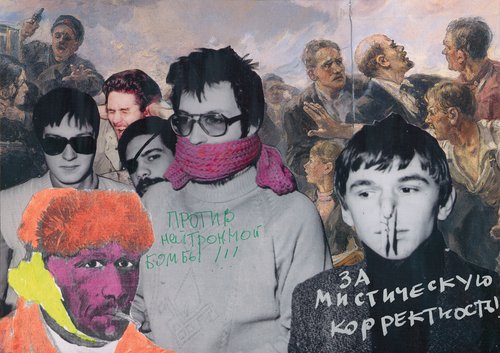

Mareev is Metamodernism personified: when he is talking to you, it’s never clear whether he is being serious or not and, like in the world of Alice, his art is a kind of puzzle without any real clues. The more you look at it, the less you understand. Is it art brut? Is it conceptual? Is it all a joke? Lenin, Putin (as judo master) and Bigfoot are among subjects somehow brought together into one exhibition. It is called ‘Communism and Buddhism’ and the title itself seems deliberately misleading. ‘It’s the name of the artwork, but it has yet to be created’, the artist explains zen style. Among the numerous sketches of anonymous people on the Moscow subway, friends, and fellow artists that he draws obsessively in his notebooks, faces of poet Alexander Pushkin and Lenin’s wife Nadezhda Krupskaya surface suddenly without explanation. For one of his exhibitions in the village he drew a ‘honorary certificate’ in Soviet bureaucratic style, listing and thanking all the people who had helped to organize it. The certificate was decorated with Soviet-style coats of arms of those national republics in the Russian federation who have mainly non-Russian populations such as Yakutia and Buryatia. They were imaginary coats-of-arms, made up by the artist himself, an oddly ambiguous commentary on the post-colonial discourse of today.

It is hard not to be swept away by what is his extraordinary imagination as well as an outstanding grasp of the fundamental techniques of graphic art. Intricately executed using tiny strokes and dots, his graphics are reminiscent of embroidery, and it is not surprising he is fascinated by insects for their tiny and complex bodies. ‘Did you know that an ant can sit back and bask in the sunshine for hours, just stroking its horns? Or that the total weight of insects on this planet is more than the weight of all the humans combined?’ he asks in a serious tone. As he seems to endlessly waver between his father’s Korean last name of ‘Lim’ and his mother’s Russian name ‘Mareev’, his painting and drawing style fluidly oscillates between realism and abstraction in an effortless way.

Alexander Mareev was trained as a painter at the Moscow State Art School in Memory of 1905 and among his first jobs were those of artist-decorator at various institutions in the decaying USSR such as the House of Cinema or the Central House of Artists. He considers himself heir of Social Realism and likes to find new uses for the methods and techniques that he learned at school. ‘For me these are spiritual riches that I can re-think, much in the same way as people re-thought icon painting. It is better to use it, rather than destroy everything and start creating something else from scratch’, he explains. He compares art to a tree trunk. ‘New rings appear, one around another as it grows. In painting it is the same thing, one layer appears, then the next one grows on top of it’. One of his drawings displayed at the Communism and Buddhism exhibition is called ‘A Sphinx and a Yellowbird’. There is a smiling, benign sphinx reciting her riddles to a rather clueless bird. The sphinx looks like an alter ego of the artist himself. When I look at his paintings and drawings in which psychedelic visions, Socialist Realism and absurd poetry go hand-in-hand, I almost see the sphinx’s smile behind them.