Works by Ukrainian Self-Taught Artist Maria Prymachenko on View in London

Maria Prymachenko. No Name. Maria Prymachenko at Saatchi Gallery. London, 2023. Courtesy of Saatchi Gallery

The artist who spent her entire life in a village near Kyiv blissfully ignored Soviet reality in her vibrant, cheerful paintings. Some of them are now on show at London’s Saatchi Gallery. Yet the main body of Prymachenko’s works, which were housed in a museum which had been once her home, were destroyed last year when the armed conflict broke out.

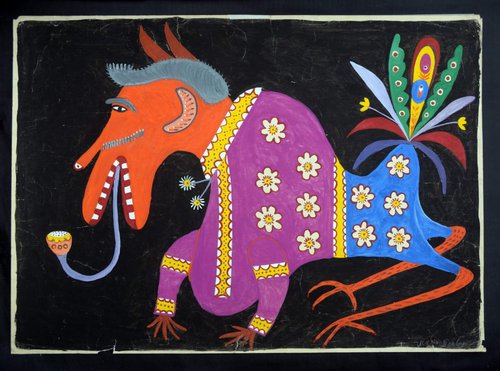

A mythical beast crouches in a summer meadow, its spotted apricot and sunflower-coloured body formed of both human and animal parts. Set in a field of delicate flower blooms, it’s a benign but strange creature, with teeth bared in a snarl or smile, we can’t be sure.

Another image shows a cow-like animal with a bird’s crest and chicken feet, stretching to eat sumptuous cherries from trees weighed down with fruit.

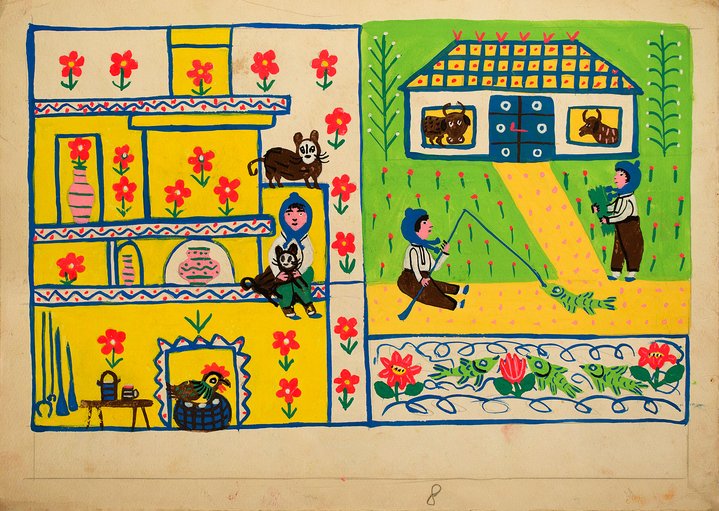

Then we see a street corner, two women gossiping over a fence; a young woman bringing in the horses, another herding pigs. Even when the scenes are drawn from life, the details are rendered in extravagant colour and form, framed in lavish folk decoration. It’s as if the whole of life exists in the territory of magic realism.

These are the vivid imaginings of Ukrainian artist Maria Prymachenko (1909–1997), whose work is currently on show in London’s Saatchi Gallery.

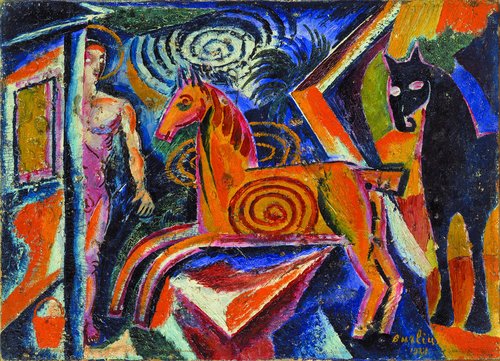

In the exhibition’s 23 works, Prymachenko takes us into an allegorical Ukrainian village where she visualizes human and natural worlds intertwined and her inner, dream world seeps into real life. These brightly-coloured works, layered with traditional decorative motifs, draw on deep historical and cultural roots, filtered through Prymachenko’s bold, compelling vision.

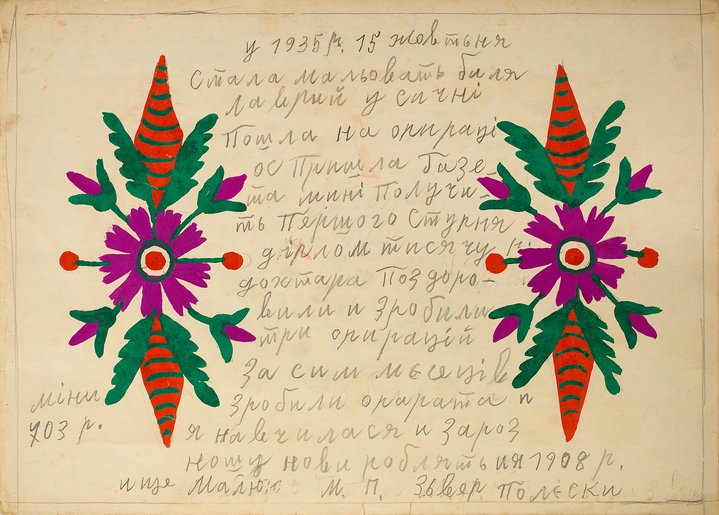

“We all know these patterns,” said Iryna, a Ukrainian visitor to the exhibition, examining the rich and extravagant floral design for a ‘ruchnik’ or wedding cloth. “When I opened the door to my Granny’s house, they were everywhere, hanging on the walls, embroidered on the duvets.”

Painting at home in her native village of Bolotnya, in the lush countryside around Kyiv, Prymachenko’s work shows no sign of the Soviet years she lived through. Self-taught, she had no formal contact with the highly ideological art education of the time and was free to draw inspiration from the timeless, rural world around her. Prymachenko’s evocation of a magical village in the nation’s heartland has become a compelling symbol of Ukraine’s unique cultural identity, and she is loved and revered by Ukranians of all ages.

In March 2022 when the Russian army entered the region around Ukraine’s capital Kyiv, its forces allegedly set fire to a museum housing Prymachenko’s works. The paintings were rescued from the flames by a local resident, according to news reports at the time.

Under the auspices of the Prymachenko Family Foundation the artist’s granddaughter Anastasia Prymachenko is working with exhibition curator Natalia Gnatiuk to develop a new museum complex at the site of her village house. But plans are on hold as the conflict in Ukraine drags on into a second year, and it’s been hard to create conditions to re-assemble Prymachenko’s works for a Ukrainian public to see.

This makes the Saatchi show all the more resonant. Prymachenko’s work reaches a wider international audience, with its rich and compelling expression of a unique, deeply-rooted Ukrainian culture under threat. “It’s bright and joyous,” said Karin, visiting from New Zealand, “but here, you feel the war is very close by.”

For Ukranians dispersed by the conflict in their country, it’s a chance to reconnect, often with personal memories of childhood, said Yevhenyia, an economist currently based in London.

“It’s a way to feel at home when you are not at home.”