Winzavod Strikes Back: Lebedev Uncensored

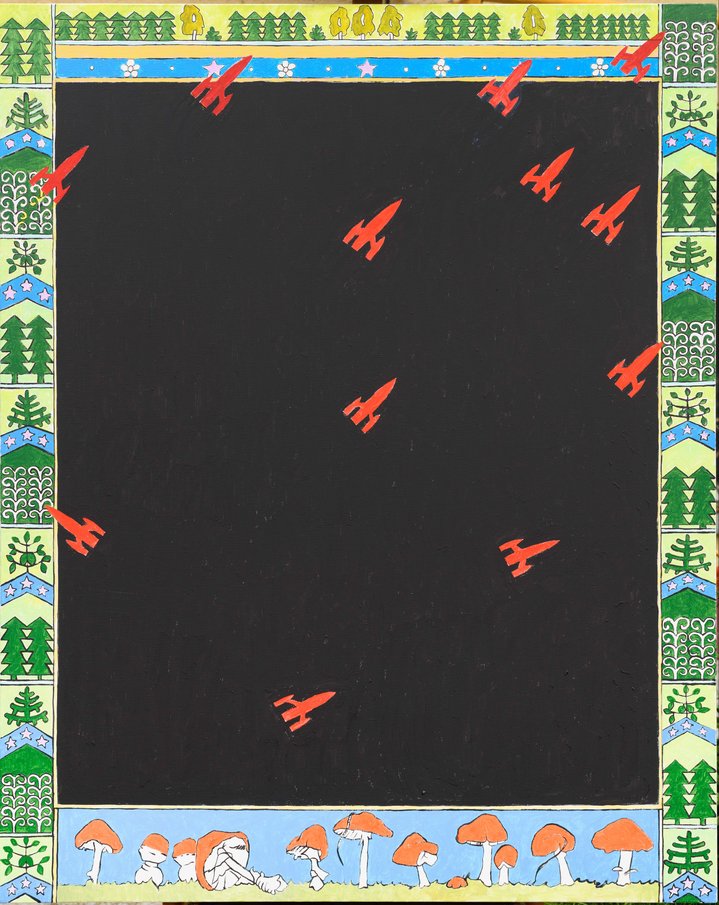

Rostislav Lebedev. Lists Are Black. Exhibition view. Moscow, 2024. Photo by Denis Lapshin. Courtesy of pop/off/art gallery

The patriarch of Sots Art has a new solo show at pop/off/art gallery at the Winzavod Art Centre in Moscow. It is a historic event because it is the first solo exhibition composed of works banned by contemporary censors.

Rostislav Lebedev's solo exhibition ‘Lists Are Black’ was launched at pop/off/art gallery shortly before his first big institiutional show ‘Rough Cuts’ closed at Moscow Museum of Modern. The gallery features works that were not shown by the museum due to censorship.

Of the censorsed works, "were there any official explanations?" Art Focus Now asked the artist. "There should be no images of Putin – no matter in what form. Images of weapons are undesirable. It is undesirable if it says 'peace' or 'war'. But these are only recommendations. The Soviet regime openly forbade things and now there are recommendations", says Lebedev, who first began to exhibit his work in the sixties. At MMOMA, not only some of the content of the exhibition was censored but the name of its chief curator, Andrei Erofeev, one of the leading independent curators in Moscow, formerly the head and founder of the Contemporary Art Department of the State Tretyakov Gallery, who assembled a collection of contemporary art for the museum, disappeared from the exhibition posters.

Five years ago, Sots Art seemed to be a dead historical style. But patriotism and censorship are twins. Sots Art has suddenly found a new breath because of what it deconstructed. Ideology has re-emerged on the historical stage.

The artistic duo Komar and Melamid (founded in 1972) put themselves in the place of Marx and Engels. Leonid Sokov (1941-2018) conflated Stalin and Marilyn Monroe and paired Lenin with a Giacometti sculpture. Yet, as the Soviet leaders have sunk into oblivion, the Russian imperial idea has surfaced from beneath their ashes.

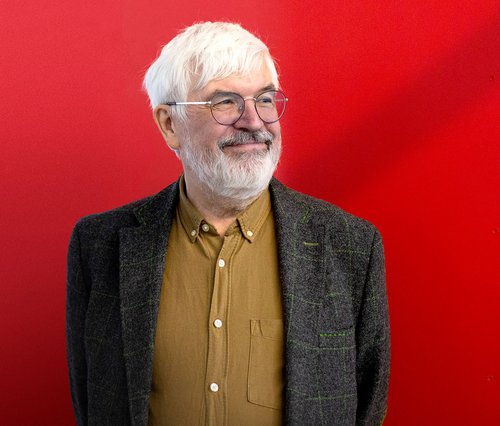

Rostislav Lebedev (b. 1946) belongs to the first rung of Sots artists. Today he is one of the few artists of this trend and of his generation of non-conformists who still live and work in Moscow. Alexander Kosolapov (b. 1943), Vitaly Komar (b. 1943) and Alexander Melamid (b. 1945), as well as the late Leonid Sokov emigrated to the USA in the seventies. Lebedev is observing and directly experiencing the changes which are taking place around him.

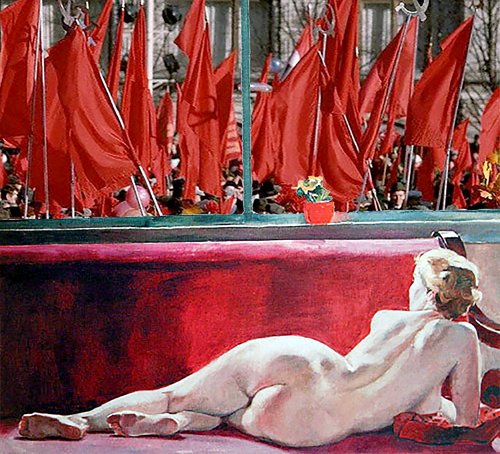

Rostislav Lebedev's USSR is a country of chocolate boxes, sweet wrappers, the Detsky Mir toy shop, the coloured inserts in Ogonyok magazine and Deineka's female gymnasts. This is the very ‘Soviet childhood’ for which the Russian counterpart of Facebook, VKontakte's meme-rich pages are nostalgic. But Lebedev problematises and defamiliarises the nostalgic content by bringing different elements together.

Kazimir Malevich's iconic ‘Red Cavalry’ storms the Spasskaya Tower, which looks more like a plastic box for sweets from the Kremlin New Year Party than its architectural prototype, while somewhere in the distance a toy pioneer trumpets, and all this action is united by the World War II slogan ‘Motherland Calls’. Each of these elements, if painted separately, could arouse felings of awe in any ultra-patriot, but it is their combination in a single picture ‘Motherland Calls’ (2022) which looks...doubtful. And doubt is destructive to ideology.

In his works Rostislav Lebedev uses a wide range of styles. His 2023 ‘Russian Cosmism’ is based on the easily recognisable style of fairy-tale illustrations by Ivan Bilibin (1876-1942) – the border forms a decorative frame of flying rockets, referring to Soviet childhood, the rockets are exact replicas of a popular plastic children’s toy in the seventies. The kidult generation more easily perceives everything that is associated with games. And Lebedev retells Sots Art in a language that is understandable to kidults.

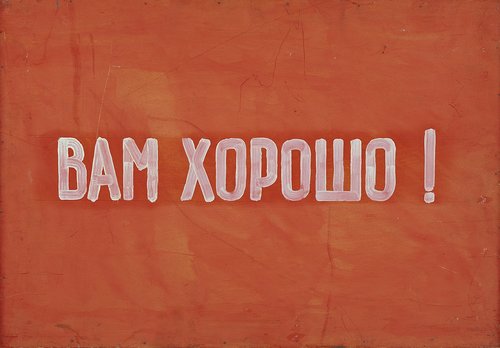

In the 2020s, millennial artists and their younger counterparts are returning to the language of the seventies, but this time it is different. Misha Rubankov, a popular artist who has a growing following among collectors, uses contemporary slogans and ads as the basis for a statement in his work. A recent work, ‘Troika’ combines the design of a subway ticket with a photograph of an NKVD ‘troika’ (a committee of three officers that had the right to sentence people to execution). In another work from 2020, Rostislav Lebedev places the red inscription ‘Stand By’ - from which the work takes its name - against the background of a police car used for the transportation of suspects which has its door open and there are officers standing by. Both artists are expressing their concerns about repressive policies.

Lebedev's post-collage painting asks questions rather than gives answers. There is no unambiguous caricature or pure grotesque, and in this way it differs rather than resembles most of the works of the Sots Artists. Even so, many of his works have proved to be unacceptable to state institutions in the new post-February 2022 reality.

Soviet censorship was strong in its anonymity. The very fact of its existence was a subject of censorship. Those who still remember how it worked are surprised at what they see as Russia's current lame attempts at censorship today, but in our information society it is impossible to preserve its anonymity. The fact of censorship sooner or later becomes known, and once known, it draws more attention to what has been censored than if there had been no censorship at all.

The forbidden costs more. In a free market, any ban draws public attention to work that is rejected. And in a situation where state cultural institutions stand beside commercial ones, any state ban only increases the power and influence of commercial galleries and private foundations.

"Now ‘censorship’ is much milder. Now it's just works that are not allowed into exhibitions. At those exhibitions in which the state takes part," says Rostislav Lebedev, "when the state dominates, it begins to dictate. You cannot compare this to the Soviet times. Now, of course, things are much better."