When Coming Home is not a Homecoming

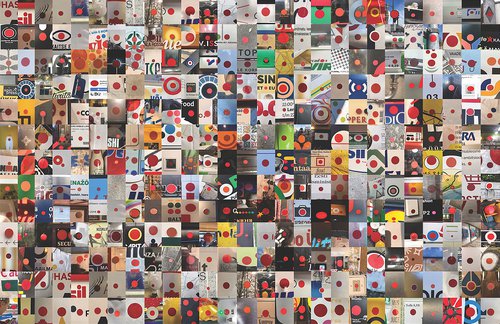

Merike Estna. Daily painting no 29, 2018. From a series of 146 paintings. Your Time is My Time. Photo by Stanislav Stepaško. Courtesy of the artist and of Mousse Publishing

A new book called ‘Your Time is My Time’ gives an overview of contemporary artists from the Baltics in the context of migration, global networks and art production while in transit and abroad.

Your Time is My Time, edited by Annika Toots and Merilin Talumaa and published in Milan, questions how recent geopolitical events have impacted the migration patterns of artists from across the Baltic countries, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. It examines the way they have learnt to adapt to working in a nomadic setting, how notions around home, belonging and community are formed within this context and how all of this shapes their art practices.

I picked up my copy of Your Time is My Time in Riga’s Kim? Art Centre where an outdoor gig and fashion show was taking place in the post-industrial courtyard to the tune of Latvian avant-garde bands boosting the mood of the arty crowd. Reconnecting with local friends, from Latvia, Estonia as well as numerous Russians who have taken refuge here since the Spring of 2022, it is no longer surprising to find each other here at one of the many crossroads of our migrant paths.

This newly-published volume offers a timely insight into the culture of artists’ migration, a topic now very close to the bone. Four essays, two interviews, and sixteen artists’ visual essays present artists that have been abroad for some time, representing a ‘culture of mobility’, in our current era of crises: the European refugee crisis (now long-forgotten, it seems) Brexit, Covid, and Ukraine all contributed to influencing the migration patterns of artists.

Artists travelling for work, education or to broaden their horizons is no new phenomenon, think of the Grand Tour, though unlike their historical precedents this book’s protagonists are mainly women. Since the end of the Soviet Union and accession of the Baltic States into the EU in 2004 this mobility was set into motion. Some artists have oscillated between two locations, a Baltic home and another in Western Europe or America; some are constantly travelling and changing countries. But of particular interest in this book are those artists who went abroad and subsequently returned to the Baltics. Although there is no clear conclusion, the third (and final) part of the book called ‘The Second Migration’ foregrounds this category through lengthy interviews conducted by the editors with two artists, Laura Põld (b. 1984) and Maria Kapajeva (b.1976), both of whom returned to Tallinn after long periods of working in Vienna and London respectively.

Whereas studying, gaining a foothold or taking part in artist residencies in the big wide art world appeals to young artists, the book finds that mid-career artists choose to bring this experience back home, and find a welcome soil back in the Baltics where they sow the seeds of their experience. It looks like a win-win strategy: the local art scene is reinvigorated by these experiences and by the knowledge and contacts gained abroad, and the artist has the opportunity to make a meaningful impact on their homeland’s art trajectory.

Yet it seems clear that this choice is not definite and permanent and the notion of home becomes and remains fraught and fluid. “Coming back to Estonia is not really coming back,” says Kapajeva, as she experiences it as a ‘second migration’. Their experiences and emotions are re-worked in the artists’ practice, for Põld such topics are “Perception of space and landscape, anonymity, relationships, cultural misunderstandings, seeking one’s own place, being stamped as an Eastern European”.

The books visuals in the form of snippets of image selections by each participant, with a short artist biography as an introduction give limited insight into the individual practices of each artist. The two editors highlight the tendency artists have for self-analysis when it comes to their migration patterns, often positioning themselves as self-directed sociologists.

What are the book’s target audiences? Is it for art enthusiasts, professionals or sociologists? On the one hand it seems to fall through a gap, falling short of becoming widely popular, too sociological for art-lovers, too arty for sociologists. And yet many sentiments speak directly to me as I dabble in and deliberate along these lines of Eastern-European artistic nomadism and I am surely not alone in this. Maybe we are a new generation of a kind of semi-artistic, semi-nomadic creative class?

“I am an immigrant, like a readymade, I lost my former place and function in order to gain new meaning.” writes curator and scholar Sandra Skurvida in her contributing essay, comparing herself to Duchamp’s urinal. Yet, multi-media ceramic artist Laura Põld (b.1984) talks about the heaviness and coldness of fired ceramics, making it a difficult medium for the nomadic artist, so perhaps the migrant artist is not a finished urinal, but one yet unfired, fragile and open to potential re-moulding depending on local plumbing.

Your Time is My Time

Edited by Annika Toots and Merilin Talumaa

Mousse Publishing, Milan, 2023