Vladimir Weisberg in Search of Heaven

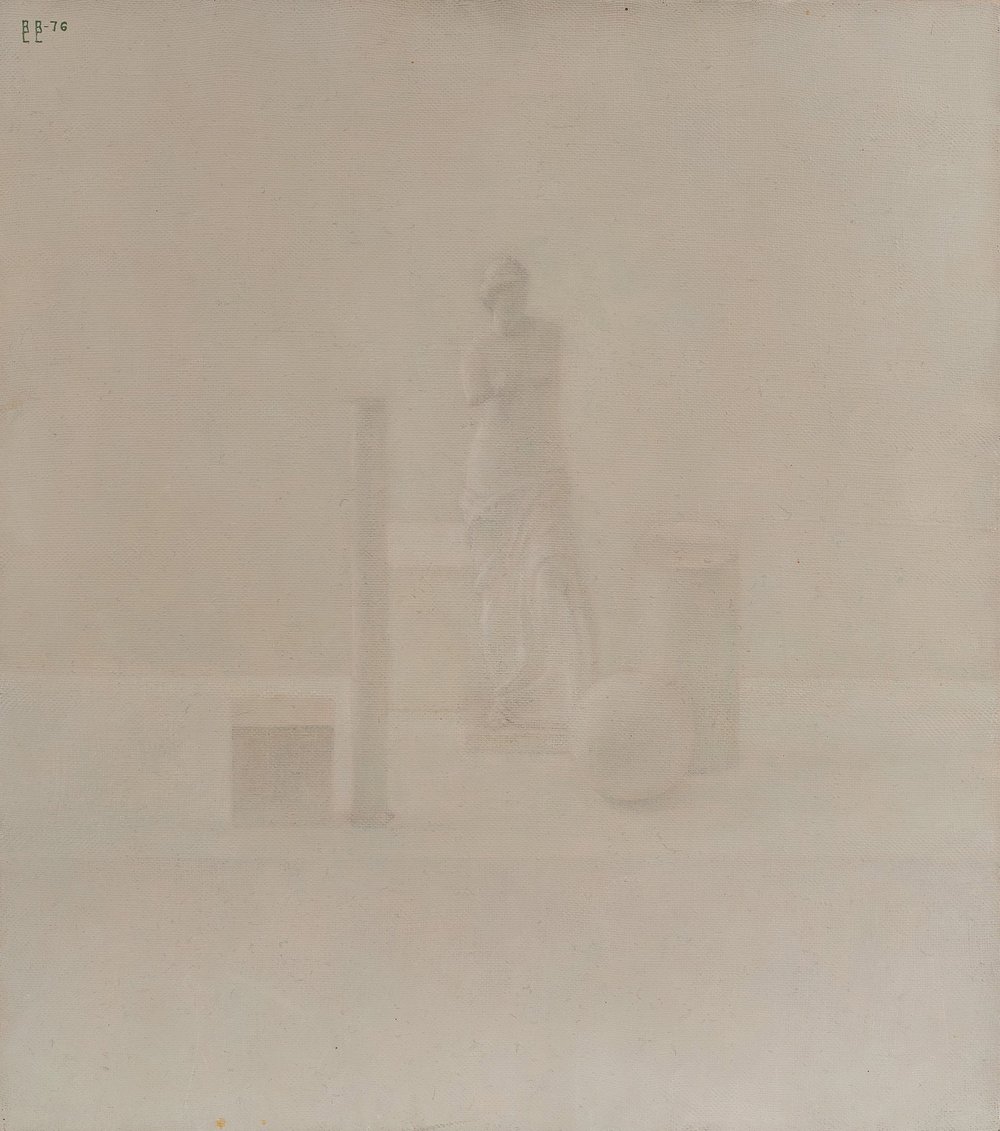

Vladimir Weisberg. Venus with geometric shapes. InArtibus collection. Courtesy of The Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts

The solo retrospective ‘From Colour to Light. To the Centenary of Vladimir Weisberg's Birth’ at the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts in Moscow is a chronological walkthrough of the artist’s oeuvre which leaves nothing out.

Recognition, fame, love and admiration only came Vladimir Weisberg’s way after his death. The first solo exhibition of one of Soviet Russia’s greatest artists (1924–1985) took place at the State Tretyakov Gallery in 1988, it was a turning point in his posthumous reputation for an artist who had prior to that only been known among a narrow circle of students, admirers and a few collectors.

In 1961 Weisberg became a member of the USSR Artist’s Union and was a lecturer in the studio of the Institute for Professional Development of the Union of Architects of the USSR for twenty years. His work featured regularly in various group exhibitions. These were, however, only the external contours of a life notable for the artist’s unwavering search for his own path in art, what was an unstoppable search for truth and perfect harmony.

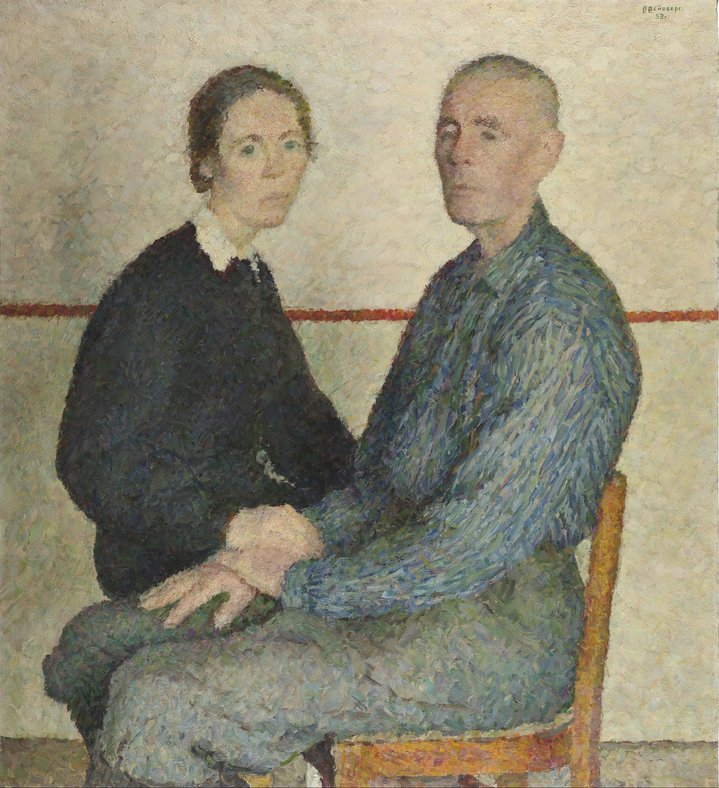

While the current exhibition brings together Weisberg's works from several museums and private collections, the majority of the items on display come from the Pushkin Museum itself. The artist's widow donated a significant collection of his paintings and works on paper to this institution. Anna Chudetskaya, an art historian and expert on the work of Weisberg who wrote his monograph and was associated with the Pushkin for many years, oversaw the preparation of the exhibition. Chudetskaya developed the concept of the retrospective, selected works and was responsible for the layout. Following her recent tragic death in a car crash, museum staff honoured her vision. The exhibition not only presents the evolution of Weisberg's oeuvre from bright multicoloured canvases to pale, almost monochromatic ones and from colour to light, but also explores in some detail the artist's search for perfect harmony.

As Weisberg said, in words recorded by his student Ksenia Muratova: “Harmony for me is a kind of homogeneous light felt gradually through the structure. This light is beyond our senses.”

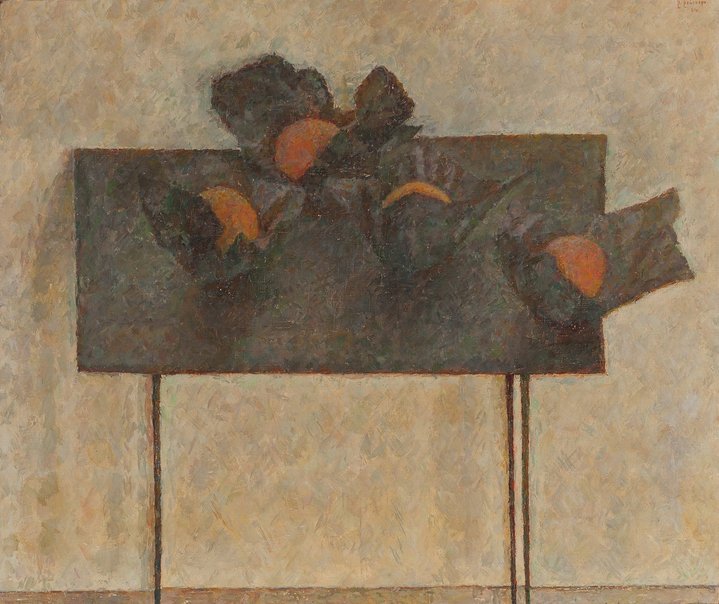

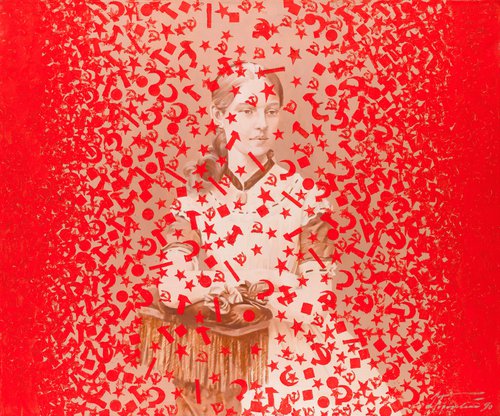

The first two rooms of the exhibition show bright, pastel and quite realistic still lifes of the 1950s. For those more familiar with his ‘white on white’ compositions it is hard to accept these as works by Weisberg, but a walk through successive rooms in the exhibibition quickly make evident the changes in the artist's style. The title ‘Oranges in Black Wrappers on a Black Table’ of a 1961 still life shows how brightness, contrasting colours and their complex combinations ceased to preoccupy Weisberg.

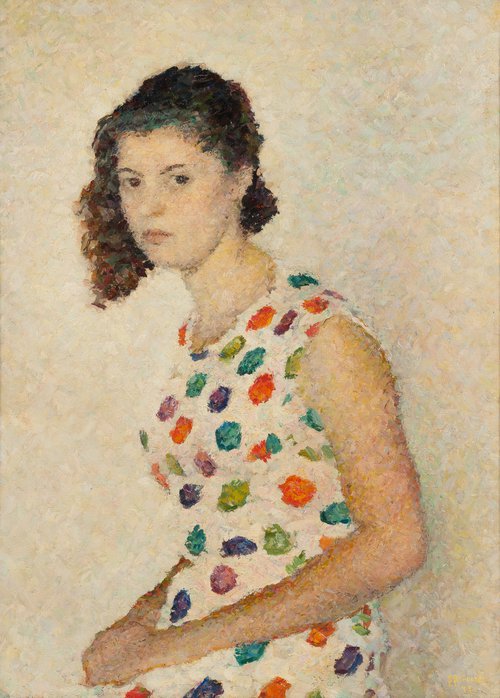

In a portrait of ‘Masha Lebedinskaya’, painted two years earlier, in 1959, we can already see that the artist is far less interested in the external resemblance to the model or her character than in the colour interchange of the circles on her dress with the strokes of the background. While there is no dissolution of the figure in the background of the painting yet, a hint of intention for this is already discernable. Furthermore, in the female portraits painted ten and twenty years later, the faces are almost devoid of individual features. They appear only in the background, as if the heroines of the portraits exist not in the real world, but outside it, as though in some parallel universe.

“If our vision were perfect, we would no longer distinguish objects, we would see nothing but harmony,” Weisberg once told his students. In Muratova’s notes, he is quoted as saying: “We cannot be in divine harmony. We set ourselves visual motives. But our craving for the sublime always goes against our immediate sensations” and “Colour exists, but it constrains me. When I am taken over by feelings, consciousness, understanding of the truth, I am not afraid to free myself from colour.”

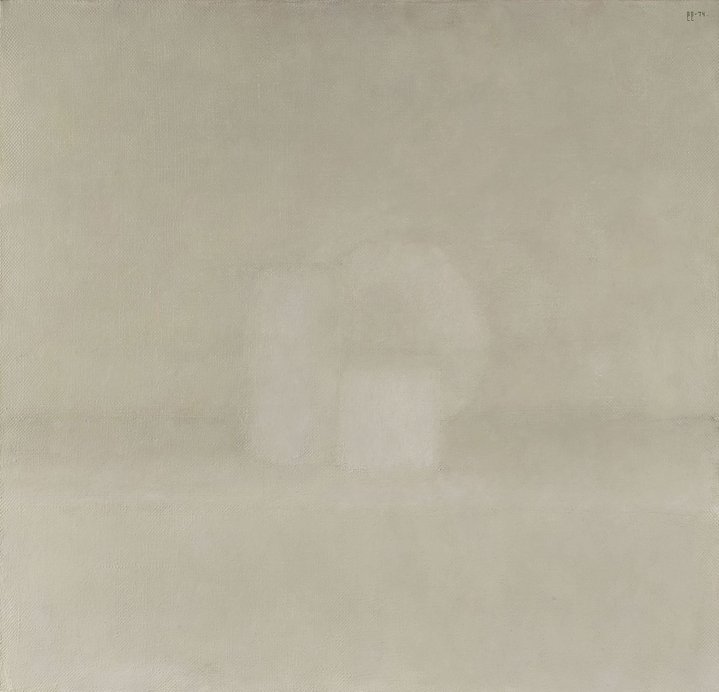

It goes without saying that there can be no complete liberation of painting from colour. But Weisberg came within a hair’s breadth of it, using in his ‘white’ paintings pale colours that were close in tone to one another. By this time, the use of people as models for his paintings no longer interested him. Instead, his compositions depict white geometric objects – cubes, cylinders, balls – and small plaster models of classical statues.

From Colour to Light. To the Centenary of Vladimir Weisberg's Birth

The Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts

Moscow, Russia

26 March–30 June, 2024