Unseen Treasures of Socialist Design on Show in Berlin

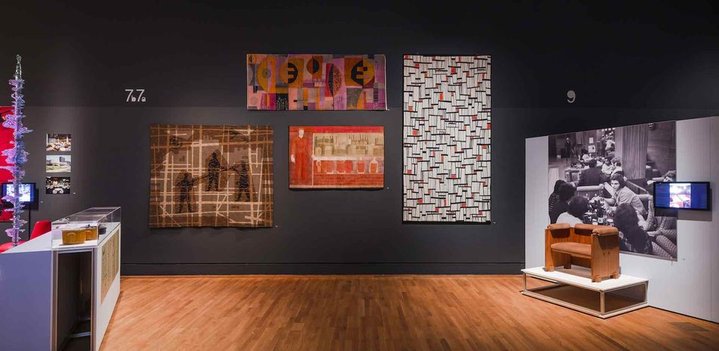

Eastern bloc retro has a new appeal today among young contemporary audiences, which Retrotopia, an exhibition at Berlin’s Kunstgewerbemuseum addresses from a fresh post-colonial perspective. Little of it was actually made or produced at the time and now these designs themselves have become ‘pure art’.

From the era of post-war reconstruction till the late 1980s, through the lens of everyday life, this show examines design across the socialist countries of Central and Eastern Europe. The focus is on spaces meant for communal use in cities or factories and private housing comprising residential buildings, apartments and their interiors.

Broadly, the socialist states in Central and Eastern Europe formed a loose belt of postulated socialist utopia, a spectrum of attitudes between the market-oriented west and the rigid centre, which was the USSR. Everywhere in the socialist block and Yugoslavia, the economy was plan-based, and the ideological dogmata were of paramount importance, although it was different between states and republics. In contrast, design was a territory where communication with the West was possible and even desirable, be it via festivals and sports events, or via representative units like airports and hotels.

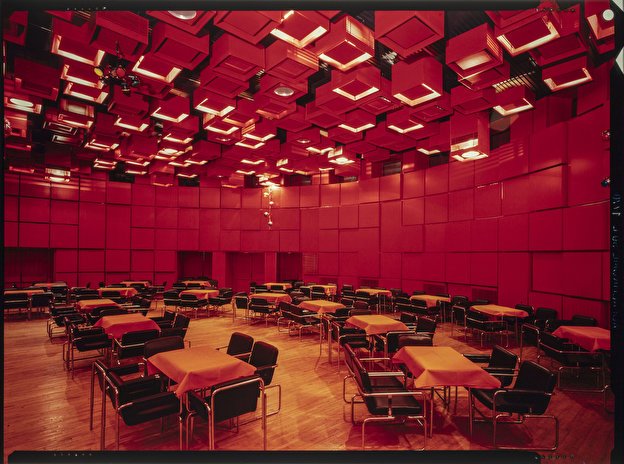

The exhibition in Berlin’s Kunstgewerbemuseum (Museum of Decorative Arts) is curated by writer and art and design historian, Claudia Banz. It was an impressive exercise in cross-country networking with eleven co-curatorial teams in post-socialist countries involved each represented in the show in a dedicated capsule. The co-curators of each capsule chose their own theme, highlighting two design projects, one public and the other private. For example, for their public design project, the Slovak capsule co-curated by Klara Presnajderova presents the Government Lounge at Bratislava airport (1972–74), designed by Vojtech Vilhan (1925–1988) with Jan Bahna (b. 1944). Although its interiors look high-tech, all were in fact created by hand and not intended for mass reproduction. The Slovak private project co-curated by Vera Kleinova is called ‘Slovak Design and Craft in Private Spaces’ and shows wooden chandeliers from the 1970s.

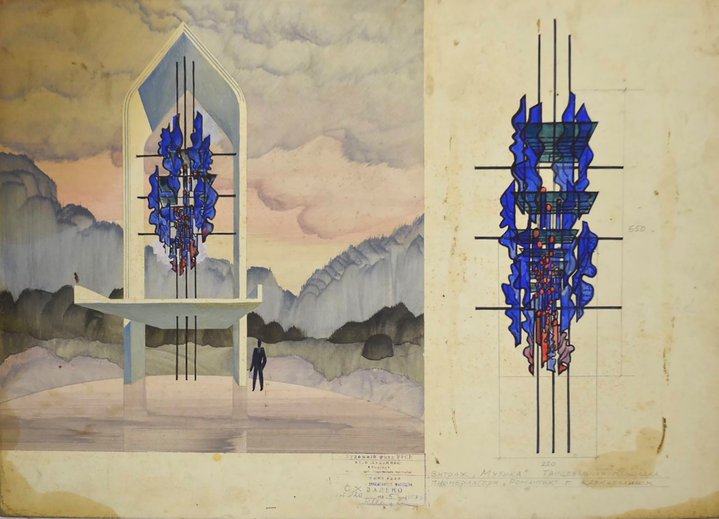

The exhibition’s narrative is linear, and the first capsule is dedicated to Ukraine. Co-curated by Polina Baitsym, its public project is called ‘Through the Magnifying Glass, and What We Lost There’, dedicated to stained-glass production of socialist era Ukraine, with artists like Oleksandr Dubovyk (b. 1931) and Anatolii Manokhin (1952–2020) among others. Some of the works, like the windows of the Chaika palace of culture (1981–82) by Timofii Syvukhin and V. Avdieienko in Mariupol or the windows at the faculties of Biology and Geology at the Kyiv National University (1986) by Larysa Michchenko (b. 1941) have been destroyed by Russian bombing in 2022. Others, like windows at the Kyiv Hospital No.4 (1988–89) by Olha Vorona (b.1961) were lost due to negligence.

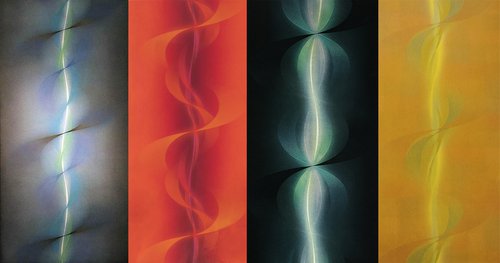

It is not the only project around stained-glass. The Lithuanian capsule, curated by Karolina Jakaite, revolves around cosmic vision. Although both Ukraine and Lithuania were republics in the same USSR, their designers approached the medium in different ways. A good example is the 1965 ‘Cosmic Fantasy’ for the Ciurlionis National Museum of Art in Kaunas, designed by Algimantas Stoskus (1925–1998). A private version of cosmic visualization is the famous 1962 Saturnas vacuum cleaner by Vitautas Didziulis, a home appliance produced until 1975 and seen in many Soviet homes. One of the problems with socialist design was that its best examples rarely were produced in quantities that would saturate the demand; by the 1980s socialist states suffered from goods deficit.

In a sense, design existed in thin air, as it could not affect production and was often shunned by industry. “The very term ‘design’ was replaced by two separate notions: ‘artistic engineering’ and ‘technical aesthetics’, standing for design practice and design theory,” – says Dr Alyona Sokolnikova, a Berlin-based independent researcher and writer, and co-curator for the Utopia in Plastic and Paper capsule.

The capsule is dedicated to Moscow’s 1962 VNIITE, a refuge for design researchers. Sokolnikova explains the alienated attitude between VNIITE and Soviet industry, that was not open to incorporating new, visual ideas into production, as the latter may have negatively influenced volume targets. So VNIITE ventured into pure utopian fantasizing. Included in the exhibition is the DIM project, a portable audio and visual information stand (1969–72), designed by the VNIITE team – Evgeny Bogdanov (1946–2021), Vladimir Paperny (b. 1944), Vladimir Rezvin (1930–2019), Alexander Ryabushin (1931–2012), A. Sergeev and POZITRON Leningrad research and development association and the GIRIKOND research Institute. It was the first Soviet attempt at a ‘smart home’ ecosystem and was created at a time when the very idea of personal computer was alien: computers were bulky and in small numbers, and the designers saw it as a pure science fiction.

This and the other projects by VNIITE shown in the exhibition are represented by either photos or reconstructions, half-scale for DIM (complete with a 3D video visualization downloadable via a QR code), full-scale for SFINX Superfunctional Information and Communications Unit (1986-87) by Dmitry Azrikan (b.1934), Igor Lysenko (b.1961), Marina Mikheeva (b.1949), Alexey Kolotushkin (b.1956), Maria Kolotushkina (b.1960), and Elena Ruzova (b.1962). The SFINX was similar to today’s smart TVs, incredibly prescient.

Some of the objects at the exhibition bring on a serious sense of ostalgia, like the Saturnas vacuum or the 1971 ‘Radikal’ wall unit by Gerald Neusser (b. 1929) made from solid wood, veneer, chipboard and glass. For those old enough to remember them, memory edits out the daily grind and preserves only the best impressions. It is these ‘best of’ moments are highlighted in the exhibition, it seems the young have a taste for the soviet times that they never lived through, embracing the cool vintage design of the era, they cannot be blamed for the fact that in reality there were few such luxuries.

The biggest takeaway from this exhibition is the touching curatorial search for cultural unity or a common visual language for the once-socialist countries of Europe, that would be post-colonial, post-ideological and not revolving around any given centre. This diversity in unity is implied but is very difficult to pin down.

The exhibition is accompanied by a catalogue containing more projects from the participating countries.