United States of Armenia: an Eye-Opening Exhibition in New Jersey

Armine Galents. Katoghike Church in Talin, Armenia, 1983. Norton and Nancy Dodge Collection of Nonconformist Art from the Soviet Union. Photo by Peter Jacobs. Courtesy of Zimmerli Art Museum

A current exhibition at the Zimmerli Art Museum challenges assumptions about artistic freedom in the Soviet era, revealing how Armenia emerged as an unexpected haven for modernist expression. Drawing from the renowned Nancy and Norton Dodge Collection, the show sheds light on a little-known chapter of cultural history.

In terms of its cultural climate, Soviet Armenia was far more liberal than Russia proper. The air of relative freedom even earned the small Transcaucasian republic the nickname ‘the United States of Armenia’. Julia Tulovsky, head of the Department of Nonconformist Art from the Soviet Union and Arts of Eurasia at the Zimmerli Art Museum, told me this anecdote as we enter ‘Topographies of Dissent’, an exhibition she has co-curated with her Armenian colleagues, Lilit Sargsyan and Armen Yesayants. The exhibition itself immediately justifies the moniker. It seems as though freedom of expression in the republic was not at all constrained. As you wander through the exhibition space, you notice an array of influences that are often surprising and unexpected.

Armenia has a long and painful history of emigration, fuelled by the 1915 genocide, and a large diaspora community overseas. With more Armenians living outside the country than within its borders, and with some diaspora artists returning from abroad, the local art scene has somehow managed to retain a cosmopolitan vibe, even during the Soviet era.

Hagop Hagopian (1923–2013), for example, was born in Egypt and moved to Soviet Armenia in the 1960s. “Art in Egypt has many French influences. It is a tradition that differs greatly from the Russian and Soviet schools of academic painting,” Tulovsky explained. The exhibition is divided into five chapters, one of which, ‘Facets of “Formalism’, showcases local interpretations of international modernist movements, ranging from Cubism to Surrealism. Arshile Gorky (1904–1948), who was born in Armenia and became one of the founders of Abstract Expressionism in America, was another major influence, despite never returning to his homeland after emigrating to the United States as a teenager in 1920. Armenian painter Hohvannes Zardaryan (1918–1992) saw his work at the Venice Biennale in 1956 and brought home a catalogue of his works, setting off a wave of homages and imitations. The painting ‘Bobo’ by Kiki (Grigor Mikaelyan) (b. 1956), a centrepiece of the ‘Abstraction’ section of the show was obviously inspired by Gorky.

All of the artworks in the exhibition come from the collection of Nancy and Norton Dodge, which was bequeathed to the Zimmerli Museum at Rutgers University. In recent years, the Zimmerli has been bringing lesser-known parts of the Dodge collection into the limelight, exploring areas that were once considered peripheral, such as art from the Baltics and Georgia. Now it is Armenia’s turn. Out of the 27,000 works of ‘unofficial’ Soviet art in this collection, around 500–600 originate from this republic. Due to space constraints, the curators have included just 60 artworks in the exhibition.

It seems that the boundaries between official and unofficial art were far less rigid in Armenia than in Russia. Many artists followed in the footsteps of Martiros Saryan (1880–1972), a renowned Soviet classic known for the vibrant colours in his paintings. Like their mentor, they attempted to express national identity through landscape. Their works comprise a dedicated section, ‘National Landscape: Land, Identity, Dream’, introduced by a watercolour by Saryan himself. For Armenians, the rugged, barren landscape of their country has strong political significance since their homeland's territory gradually shrank throughout history. Even Mount Ararat, a cherished national symbol, now belongs to Turkey. The recent armed conflict with Azerbaijan over Nagorno-Karabakh makes this section of the exhibition particularly relevant. While many churches in the disputed area have been destroyed during the war, the painting of a church by Armine Galentz (1920–2007), a Syria-born artist who was also a repatriate, looks like a testament to tragic loss and resilience.

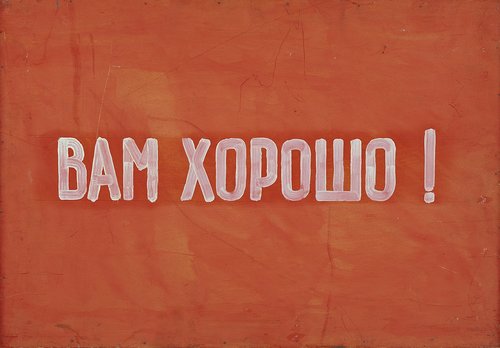

Soviet censorship in Armenia was so relaxed that an artist could bypass it simply by changing the label. This is the story behind Hagop Hagopian’s artwork, which opens the exhibition's darkest chapter, ‘Dystopias of the Evil Empire’. The painting depicts an eerie crowd of headless people rallying on an endless plain, and the anti-Soviet message is so obvious that the artist never intended it to be shown at an officially approved exhibition. However, after reading a newspaper article about the invention of the neutron bomb, he gave the painting the title ‘No to the Neutron Bomb!’. With its message thus aligned with Soviet anti-war propaganda, the painting appeared in many exhibitions. The curators have created an elegant visual rhyme by placing a photograph of a beheaded Lenin statue being dismantled in post-Soviet Yerevan (by Zaven Sargsyan, b. 1947) at the entrance to the exhibition. This striking document and Hagopyan's bold fantasy echo one another, proving that even the most surreal artistic visions can become reality. Other artworks in this section also criticize the Soviet regime indirectly and symbolically. For example, Raffi Adalyan’s (b. 1940) ‘Gulag Archipelago No. 2’ (1984), an assemblage of shoes glued onto a board, evokes the many Holocaust memorials where old shoes have been turned into monuments to their owners, who perished in death camps. The idea that the Nazi and Stalinist regimes employed similar mechanisms of destruction predates the heated public debates about the Great Terror repressions during Gorbachev's perestroika – an era of liberation in the USSR that began in 1985.

The final chapter of the exhibition is dedicated to the ‘Third Floor’ group, a collective of young conceptual artists who challenged academic and non-conformist conventions alike. Drawing inspiration from Western counterculture, they fused the aesthetics of comics and collage with national motifs. Their art is full of youthful energy and refreshing irreverence. Karine Matsakyan’s (b. 1959) ‘Half-Hourly Difference’ (1985–1986) combines Pop Art imagery with a feminist protest against the commodification of the female body — a powerful yet unexpected combination. Thus, the exhibition concludes on a positive note with Perestroika and its high hopes for a new beginning. However, this optimistic finale is deceptive. The tragic events that followed, from the catastrophic Spitak earthquake of 1988 to the bloody wars with Azerbaijan that began in the 1990s and continued into the 2020s, lie beyond the scope of the exhibition. Constrained by the chronological limits of the Dodge Collection and the modest size of the galleries, the exhibition makes the artistic heritage of Soviet Armenia appear like a sunken Atlantis, despite the fact that many of the artists featured in it are still alive, and some attended the opening reception. As viewers leave the museum, the question ‘What came next?’ lingers in their minds. In any case, as the largest exhibition of Armenian art in America to date, ‘Topographies of Dissent’ hopefully paves the way for further exploration of this multifaceted subject.

Topographies of Dissent: Armenian Art from the Dodge Collection

New Brunswick, New Jersey, USA

27 September 2025 – 31 July 2026