Ukrainian artists fascinated by the human body

Installation view, Restless Bodies by The Naked Room (Kyiv) at NOME (Berlin), 2022. Courtesy of NOME gallery

Berlin’s Nome gallery is playing host to ‘Restless Bodies’, an exhibition curated by Kyiv based art gallery, The Naked Room. It brings together works by young and mid-career Ukrainian artists reflecting on the human body from unconventional perspectives.

Founded back in 2018 by independent art curators Lizaveta German and Maria Lanko, and Swiss film director Marc Wilkins, The Naked Room exhibits up-and-coming Ukrainian artists. As one of the artists explains, the title of the show, ‘Restless Bodies’, alludes to how students at art schools in the Ukraine spend a lot of time learning how to sketch the human body according to academic traditions which they later use as a starting point for further explorations.

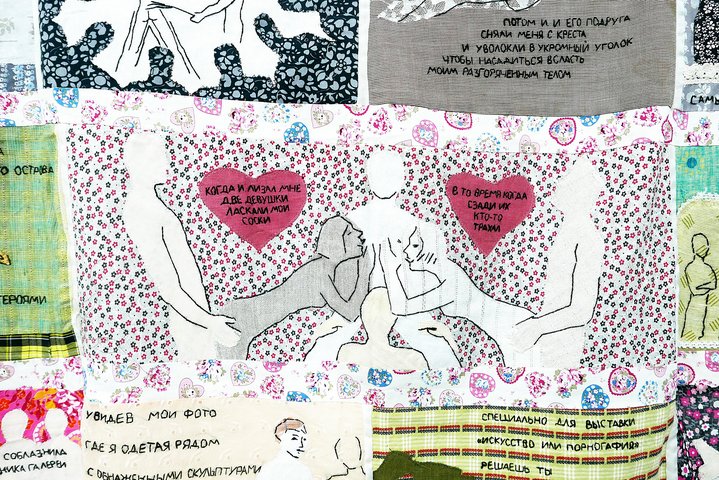

A canvas at the entrance to the exhibition depicts amorous adventures in needlework: the protagonist is flagellated while ten other men are watching, pleasuring themselves; she engages in intercourse on a mini-golf course or sleeps with strangers. There is an upbeat style, the needlework is made with patches of lace and different patterned fabrics from bedlinen. It is almost disturbingly frank, and adventurous, especially when you learn that the artist, Alina Kopytsa (b. 1983), was inspired by her own pleasure seeking experiences during her first trip to Berlin a decade ago.

And yet both pleasure and pain coexist in the space of this exhibition. Other small embroideries made by Kopytsa from vintage lace placemats, show people dominating in BDSM practices. Katya Libkind (b. 1991) has made a series of pencil sketches in which people with Down syndrome are engaging in sexual intercourse, often, similarly, in a BDSM setting. Through the bare intimacy of these scenes and the pencil lines, the drawings create a feeling of voyeurism and discomfort, and accentuate vulnerabilities.

Sasha Kurmaz (b. 1986) presents a series of screen prints taken from pictures in forensics books. Printed in intense hues of red with white, they blur the bodies and wounds, and yield the atrocious aspect of their content before one can take a closer look. The prints are accompanied with bronze objects resembling knuckles and torture instruments that turn the abstraction of forensic prints into a possibility. Kristina Melnyk (b. 1993) paints close-ups of wounds in a technique used for painting Orthodox icons known as levkas, which is a mixture of fine alabaster powder, gypsum, and glue applied in layers to a surface later gilded with gold leaf. And even though stitches are still visible in the painted wounds, the result is unidentifiable, turning wounds into abstraction, as if in reverse order to the works of Kurmaz.

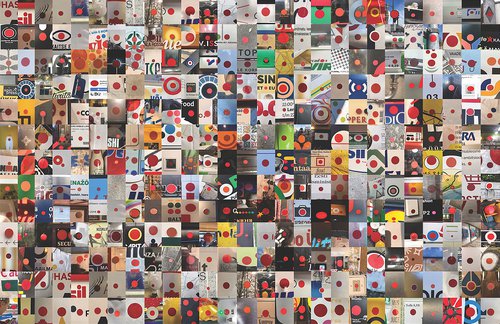

In ‘Mutilated Myth’ by Nikita Kadan (b.1982), cropped black and white photographs of people are pasted on top of illustrations from Bruno Schultz’s ‘Book of Idolatry’. There are two layers: the idol of a woman unattainable to men who surrender themselves in front of her, usually prostrated at her feet, as in Kadan’s bigger Goyaesque painting where some of the men even look like corpses on the floor; and small squares with faces of people documented during the 1941 Lviv Pogrom. How are the same beings crossed with such strikingly different emotions? Where does idolatry turn to power play? Where does power turn to violence, torture, and massacre?

In ‘Mutilated Myth’ by Nikita Kadan (b.1982), cropped black and white photographs of people are pasted on top of illustrations from Bruno Schultz’s ‘Book of Idolatry’. There are two layers: the idol of a woman unattainable to men who surrender themselves in front of her, usually prostrated at her feet, as in Kadan’s bigger Goyaesque painting where some of the men even look like corpses on the floor; and small squares with faces of people documented during the 1941 Lviv Pogrom. How are the same beings crossed with such strikingly different emotions? Where does idolatry turn to power play? Where does power turn to violence, torture, and massacre?

Tortured bodies are the subject of Kateryna Lysovenko (b. 1989)’s works. Victims of the Russian invasion of Ukraine are seen as figures from an alternative mythology, some with the bodies of a centaur, some enlarged, bloated, monstrous, corpses returning to those alive. They are protagonists of a different reality than the one we witness in the mass media.

And speaking of the clashes of realities, after the fall of the Soviet Union, freshly independent Ukraine had to reissue passports for its citizens. The State police hired photographers to visit the elderly and the incapacitated in their homes, and take their passport photographs against a backdrop of a white sheet. Alexander Chekmenev (b.1969) documented this process in the city of Lugansk in his ‘Passport’ series: while the close-up portraits would later be used for official purposes, the exhibited photographs are taken from a distance of three steps away. As a result, we cast an intrusive look into the homes of the elderly, dressed up for the occasion, held up by others. Women in dresses, men in suits, barefoot, squinting hard into the camera, are sitting next to their unmade beds and startled relatives, their rooms squalid and poor. One of them stores her things on the lower bunk of a bed, and in a coffin wrapped in bright red cloth, on the upper bunk. These ‘restless bodies’ seeking eternal rest.

Restless Bodies. Nome hosts the Naked Room

Berlin, Germany

October 26 – November 18, 2022