Tuxedo and Turpentine: What’s New in a New Biography of Kandinsky

Olga Medvedkova. Kandinsky. Corps et âme. Book cover. Courtesy of Flammarion Editions

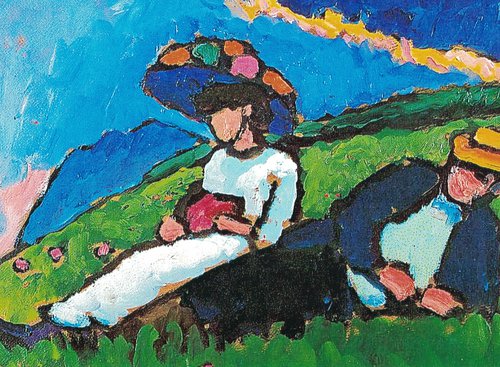

A year before the 160th anniversary of the birth of Wassily Kandinsky (1866–1944), a new biography of the artist has been published in French by Flammarion Editions, written by art historian Olga Medvedkova.

“Making a mess in the studio is proof of an artist’s bad taste. I can paint in a tuxedo”, Wassily Kandinsky used to say, according to his widow Nina. While photographs of French artists of the era often show them in smocks, Kandinsky preferred to pose for photographers in a formal suit.

Kandinsky was a man of routine, spending a significant part of his life strictly according to the clock: getting up at the same time, having breakfast at nine with the same meal every day, working until half past twelve, an hour for a walk, lunch served by one thirty (reading during lunch, no chatting at the table!), half an hour’s nap, then a cup of tea with lemon, and working again until sunset. This routine continued for the last decade of his life in Paris, from 1934 to 1944. The eleven years he spent in Weimar and Dessau, from 1922 to 1933, differed only in one detail: the first half of the day was dedicated to teaching.

The new biography of Kandinsky paints a paradoxical portrait of the great artist as a nearly Kafkaesque character. A reserved snob in his youth, a typical graduate of Moscow University, as described with displeasure by Russian artist and art historian Igor Grabar. A grand bourgeois in maturity - the owner of a large 24-apartment building, built for him near the Garden Ring in Moscow. A human clock in his later years. And at the same time, a romantic and visionary, a traveller and an explorer.

Wassily Kandinsky was undoubtedly one of the most educated artists of the Russian avant-garde, if not the most educated. A lawyer by training and an ethnographer by passion, with scientific publications in both fields already as a young man, he could have had a brilliant academic career but stubbornly refused the offered professorships such as the position of professor of law at the University of Dorpat (now Tartu). He could have gone into the tea trade, like generations of his ancestors. Being closely related to the wealthy merchant family of the Abrikosovs (they were the largest importers of tea in the Russian Empire, manufacturers of candies, and owners of a chain of confectioneries), he would have not worried about securing his future: it was predetermined at birth. But, once he graduated, after working for just one year as the director of the Kushnerev typolithography, one of the best publishing houses in Moscow at the beginning of the 20th century, which published illustrated books, Kandinsky once and for all abandoned business. At the age of thirty he finally decided to realise his childhood dream of becoming an artist and went to Munich to study painting.

“I remember that drawing and, a little later, painting tore me away from the conditions of reality, that is, placed me outside time and space and led to self-forgetfulness”, the artist wrote in 1913, recalling his childhood. “Even the smell of turpentine was so enchanting, serious, and strict, a smell that even now arouses in me some special, resonant state, the main element of which is a sense of responsibility”. This irresistible smell of turpentine made him forget about his career and plunge headlong into the risky world of bohemia.

It is difficult to write a new biography of this artist. He moved all his life, and documents concerning his life and work are stored in archives in Russia, Ukraine, Germany, France, and the USA. He was prolific not only as an artist but also as a writer – producing many books and articles often contradicting each other, and volumes of correspondence with his contemporaries. The number of exhibitions and their catalogues in which Kandinsky’s works were included probably numbers several thousand. Finally, and most importantly, Kandinsky is not only a studied but also an overstudied artist.

“Kandinsky studies” is a separate industry not only in art history but also in art theory. One could write a separate monograph about the reception of Kandinsky’s ideas in French philosophy of the 20th century – from his half-nephew Alexandre Kojève to Philippe Sers. Articles dedicated to the artist measure in hectolitres of poured ink. From one biography of the artist to another, one could build an entire bookshelf, starting with the first posthumous biography by his friend Will Grohmann, and ending with the latest biographical surge around 2016, when the artist’s 150th birthday was celebrated.

The Kandinsky myth has long superseded his actual persona. Partly created by Kandinsky himself, partly by his widow Nina, and partly as a result of information noise, this myth exists separately from the individual and only grows like a snowball over time. For example, the latest Russian-language biography of Kandinsky is a volatile mix of unsubstantiated information, superficial cultural studies, naive psychology, essayistic descriptions of paintings, and authorial reflections (i.e., the author’s self-reflection through Kandinsky).

This myth spans from the origin of the Kandinsky family name to the death of his widow. Information about Kandinsky’s descent from the “princes” of Konda, i.e., the Finno-Ugric people of the Ob region (without references to reliable sources), migrates from publication to publication. This is followed by a chain linking to his ethnographic article about the “god Churila” among the Komi people, then to his association with anthroposophists (who have no connection to paganism), and this snowball rolls on until the “mysterious” death of Nina Kandinskaya (is there anything mysterious about the robbery of a wealthy old woman living alone in her villa?). In this context, Kandinsky himself is portrayed almost as a shaman in the vein of ‘Psychic Challenge’.

A new book by Olga Medvedkova, Paris-based art historian, writer and Director of Research at the Sorbonne’s Andre-Chastel Centre is devoid of mythological aura; it is a research-based study (the author even accessed the State Archive in Odessa!). Although the book contains some unfortunate factual errors – particularly in areas most familiar to Russian readers, for example, regarding the biography of Anatoly Lunacharsky, the first Soviet Minister of Education, it provides a pleasant alternative to pseudo-art criticism. The writer does not put herself in Kandinsky’s shoes or replace documents with her own fabrications or fervent descriptions of the artist’s works, which are inappropriate for a biography.

Three distinct individuals are vividly portrayed in the five chapters of Olga Medvedkova’s new book. The first is a young Moscow careerist from a good family, aspiring to become a scholar or administrator with ambitions, before the age of thirty. The second is the Munich bohemian between the ages of thirty and fifty – a man whose head is spinning with ideas and whose portfolio is overflowing with artworks. And finally, the third is in his prime: a renowned European artist and art theorist, teacher, and organizer of public education.

Russian? German? French? He mastered each of these languages as his native tongue. Additionally, he knew ancient Greek well enough to translate Longus himself. Kandinsky’s life seemed to embody the dream of his Bosnian friend Dimitrije Mitrinović about a united Europe where creativity would flow freely without national boundaries. The problem is that this very dream led to both World Wars. To create a new Europe, one must first destroy the old one.

For Kandinsky, changes in fortune were a series of forced decisions. In 1914, he fled Germany as a conflict began in which his native country and his adopted homeland found themselves on opposing sides. In 1921, he permanently left Russia, ravaged by revolution. In 1933, he lost Germany again, when it became engulfed in Nazi madness. Each time, he left everything behind, risking never to recover his paintings, library, or belongings. While Kandinsky’s paintings have long been textbook material, his destiny is now eerily relevant.

Olga Medvedkova. Kandinsky. Corps et âme. Collecntion ‘Grandes biographies’. 2025. 368 p.

Paris, France