Thirty-something: the contemporary art of generation Y

The Russian Museum in St. Petersburg has decided to take a look into the face of a new generation of the city’s artists. Yet, the exhibition, called ‘Millennials’, brings more questions than answers

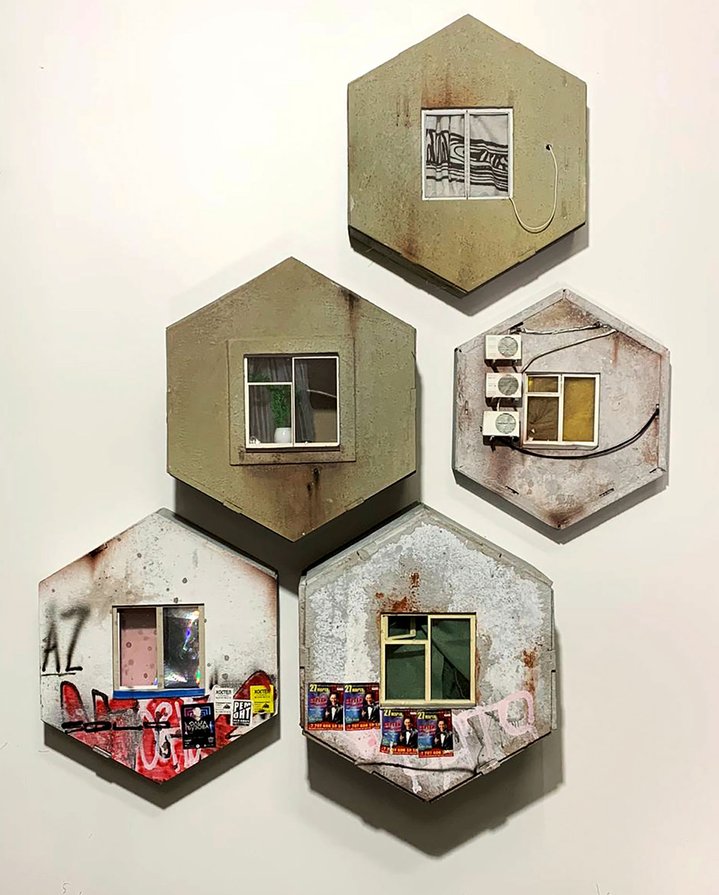

Millennials are a social group broadly defined as those born in the 80s and 90s, characterised by an upbeat, go-getter attitude. But a new exhibition in St. Petersburg’s Russian Museum might re-cast this presumption. ‘Millennials in Contemporary Russian Art’, which runs from March 4 to June 14, examines the artistic output of a city renowned for its melancholy, perfectly captured by the words on a souvenir postcard on sale in the museum’s shop: “From St. Petersburg with apathy and indifference”. The term ‘millennial’ was coined by two American sociologists, Neil Howe and William Strauss, but what distinguishes the Russian variant? The exhibition’s curator Maria Saltanova explains: “They were most likely born still in the Soviet Union, but they don’t methodically reflect upon the Soviet Union like the Sots Art movement did; it exists more in the depository of their memory in the form of echoes: grandma’s flowerpots, dacha vegetable gardens, something to do with perestroika, Pepsi-Cola, Cheburashka... these sorts of images.” The first room exudes Petersburgian melancholy. Impeccably curated, it is completely devoid of colour, filled with art works that harmoniously resonate in an understated bare materiality of wood and metal. There is a dress made of nails by Nadezhda Kosinskaya (b.1981), a welded shower by Konstantin Benkovich (b. 1981), a plank of wood by Nestor Engelke (b. 1983), hacked out somewhat viciously to reveal the form of a primitive shed; and the structure is repeated in a pile of wood chips on the floor. There is a monochrome mosaic of Mickey Mouse and Cheburashka holding hands by artist Ivan Tuzov (b. 1984). Here, although there is a broad spectrum of media and technique, the works are often intentionally handmade or antiquated, which reveals a common leaning in the group towards materiality. The physicality of material and craftsmanship is explored and brought into focus, perhaps a symptom of digital fatigue, or a material-virtual tug-of-war.

Something which Alexandra Lerman’s (b. 1980) work in fired unglazed clay Swipe Swipe Swipe illustrates almost too precisely: “The copyrighted, choreographed gestures of the ‘swipe’, ‘slide to unlock’ and ‘pinch-to-zoom’ are performed by millions each day and are owned by Apple, Inc. A series of clay smartphones are imprinted with indexical ‘portraits’ of these ephemeral and often unconsciously executed touch-screen gestures and reclaimed by the human hand in the process. Fingers to digits, silicone to clay,” the artist explains. The show features some 145 works by over 40 artists from St. Petersburg: how did curators Maria Saltanova and Anastasia Karlova, who began work on the project four years ago, make their selection? One technique was to interview each artist and ask them whom they would nominate to be included in the exhibition. The aim was to build a broad overview, partly intended as sociological study. The project’s ambition is fascinating – to use contemporary art as a kind of data pool for analysing the behaviours and mind-set of an entire generation. But, the curators shy away from a meticulous examination, instead outlining three broad and fluid categories: materiality, introspection and environment – and leave the rest to the viewer. The show cheers up with works in fimo clay, expressionist style paintings, textile dolls and bright inflatable sculptures imitating computer graphics. With humour, painterliness, complex research and concepts, dialogue with themselves and other artworks – the works are manifold and each demand individual attention. But, there are no overarching millennial trends that leap out at the viewer above and beyond the individual pieces. Reassuringly, the artworks hold their own against attempts at data-mining categorization. And yet, one can’t help but notice there is a gaping Putin-shaped hole. The year 2000 welcomed not only a new millennium, giving the generation its name, but arguably the world’s most controversial leader to Russia’s throne. Dictating the country’s direction for half of this generation’s life, the political apathy of artworks inside the museum looks somewhat unrepresentative. The show is rather tame for what one might expect of youth: here even street art has been disinfected, represented by clean replicas commissioned for the occasion. Yet, curiosity about their young talent has been drawing in much media attention and pulling crowds of St. Petersburgers ten times the museum’s daily norm. Saltanova notes with surprise that this popularity rivals only a blockbuster show of Sylvester Stallone’s paintings in 2014. With this ‘Millennial’ show, a state museum has the chance to make a direct impact on the careers of living artists and vice versa –perhaps this museumification is what this generation needs: a step up, laurels to rest on, a clean pedestal making a welcome difference from the daily grind of studio life.