60th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia. Photo by Andrea Avezzù. Courtesy of La Biennale di Venezia

The Venice Biennale Turns the Other Way

With peace itself at stake in Europe, why has the Venice Biennale turned to the Global South as the protagonist of its latest edition?

The 2024 Biennale de Arte in Venice was never going to be a walk in the park. Anyone looking from afar (or from closer to home) at the current state of affairs in Europe with its continuing war, social displacement, and wider geopolitical tensions destabilising the world and forcing us to contemplate a different future with less security, could be forgiven for feeling a little daunted at the task of curating an international contemporary art show fit for our times. Even the title ´Foreigners Everywhere´ set expectations long before the opening last week, it seemed apt and relevant looking at the numbers of Europeans displaced across our continent. Volte-face. Arriving in Venice, the reality hit that at a time when we are deeply in need of understanding, comfort and new perspectives, if not a sharing of collective grief, the mother of all biennales was looking the other way. With the exception of very few national pavilions such as Austria, Poland, and Ukraine, the current war in Europe and the enormous consequences this has brought us including high inflation, rising poverty, bigger defence budgets (when governments have unprecedented levels of debt), bombastic, military rhetoric not seen since the end of the Cold War, all of this was nowhere to be seen in Venice.

It all felt rather more retrograde rather than avant-garde, perhaps the second part of a show about outsiders on the back of Cecilia Alemani’s female Venice Biennale in 2022 which also had a strong Latin American focus. This title, translated into English as ‘Foreigners Everywhere’ is taken from a neon light installation by the art collective Claire Fontaine, a work made twenty years ago during the mid 2000s referring to an anarchist collective from Turin. Biennale curator Adriano Pedrosa, director of the impressively openminded and forward-thinking Museum of Art in Sao Palo, invites multiple interpretations, playing on the word ‘Stranieri’ which both can be translated as ‘Strangers’ and ‘Foreigners’ structuring the show around three main themes, queer art, indigenous art and outsider art. If in the 19th century we meet the lone white male in his studio garret, now many generations later, the outsider has become anyone among us, even all of us, ‘Stranieri Ovunque’. The idea of focussing the Biennale on outsiders was first introduced by Massimiliano Gioni in 2013, a decade ago and at the time it seemed radical and fresh. All of these issues continue to be very relevant as our societies rightly seek more inclusivity, yet are they the most pressing in Europe today amid the current socio-political crisis?

Loosely, this Biennale was more about the global south than anything else, a postcolonial vision whether on social immigration from the Global South to Europe or new respect for its artists, in each case both past and present. What exactly is the Global South? It has become the latest moniker for what used to be referred to superciliously as the Third World, yet it covers a multitude of countries that share very little in common and it risks likewise perpetuating a generalised assembly of countries into two competing tiers. The now antiquated world order, the First, Second and Third worlds, dissolved at the end of the cold war in part because the Soviet Union (the second order) broke up. If much is said about the democratization of the art world today, values which the Venice Biennale holds dear, when it comes to geography and ethnicity, this is generally a dialogue of decolonialisation between the old first and third world orders. Yet what about the narratives closer to home? Modern and contemporary Central and Eastern European art, and art from the post-soviet countries has remained in the periphery of the mainstream over the past three decades, with few cheerleaders on the market or in international fairs and biennales. At a time when we need nuance and understanding within Europe if not further afield, there was silence.

Some of the national pavilions come up with their responses to the current crisis. After having been shuttered during the last Biennale two years ago, this time around Russia lent its pavilion to Bolivia; Poland lent its pavilion to a Ukrainian art collective. Bulgaria, Austria, Poland, Ukraine and Kosovo all presented projects which resonated either directly or indirectly with what is happening today in Europe.

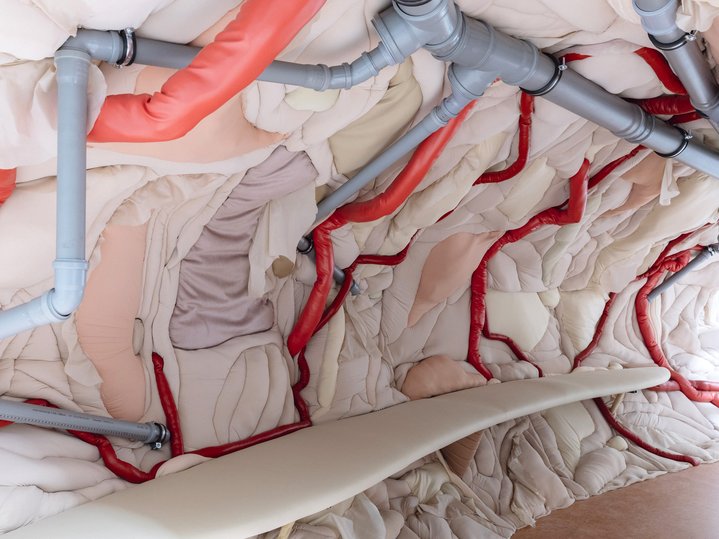

The Polish pavilion was given to a Ukrainian collective, Open Group, who presented a moving yet disturbing monumental video piece called ‘Repeat After Me II’ in which residents from across the country imitated the sounds of Russian missiles. Ukrainian based Pinchuk Foundation, a regular at the Venice Biennale, where it used to exhibit shortlisted artists in its coveted Future Generations prize, since 2022 has curated international shows about the war. In this edition’s exhibition called ‘Dare to Dream’ one of the most powerful and dramatic works on display is a life-size organ created by Ukrainian artist Zhanna Kadyrova (b. 1981), the top of the pipes being formed out of the shells of used Russian ballistic missiles.

Russian born artist Anna Jermolaewa (b. 1970) who lives in Vienna was chosen to represent the Austrian pavilion. Her ‘Rehearsal for Swan Lake’, consists of a video of this iconic Russian ballet played on a loop with Ukrainian ballet dancer Oksana Serheieva coming out from time to time to rehearse as if she is preparing for the big show. Famously broadcast on television in the Soviet times during the days of mourning of soviet leaders and again during the 1991 coup, this ballet symbolises not just a time of political upheaval but ultimately a change of regime. Jermolaewa left Soviet Russia in 1989 in the search for the freedom of expression she was denied at home and a video work at the pavilion is about her own, personal experiences as a new migrant in Vienna where she found herself initially sleeping on a bench. The Bulgarian pavillion is about the consequences and legacies of state repression in extremis based on real experiences of people who lived during communist era Bulgaria. ‘The Neighbours’ is a chilling reminder that in a highly repressive dictatorship you cannot even trust your neighbour, an afront to one of the most basic of civil values. In this immersive installation you find yourself in a dark space with three small domestic settings in which you can sit and listen to various recordings spoken by survivors of historic state repression. The curator has divided these recordings into three, those who are accustomed to speaking about their personal experiences in public, those who were talking about it for the first time, and those who were simply unable to access their memories, or put them into words, in other words, silence.

In ‘Exposition Coloniale’, the Serbian pavilion takes a far broader perspective on socio-political narratives around notions of Europe as a conglomeration of nation states, a locus for historical immigration, transformation and its position in the world as well as questions around displacement and belonging – the artist is himself permanently displaced in Germany. Conceived as an ensemble of several small immersive sets comprising a bedroom, bathroom and bar which you can stroll around and enter, it feels like a film set reflecting the artist Aleksandar Denić’s work as a theatre set designer. The first thing you encounter is a massive, illuminated sign with the word EUROPE just below the ceiling and by the wall, but facing the wall, we find ourselves on the inside. Here we encounter vintage detritus, crates of empty coca cola bottles in a cabinet locked under padlock; elsewhere in a small gloomily lit bedroom hanging from a top corner there is an old vintage television blasting out the 1971 iconic coca-cola ad, more recently recycled at the end of ‘Mad Men’, the global blockbuster American TV series which defined the 2000s. The words sung in happy unison, Ï like to teach the world to sing and furnish it with love´ culminating in the famous jingle Ít´s the Real Thing´. In this setting in the middle of the Venetian giardini, I find myself asking the question - what is real? Is Europe really a North American colony? Or is the promise that it holds for immigrants fleeing political asylum real? Or are we Europeans just consumers in a global marketplace? Whatever, Denić tells us, don’t worry, we are in a film set, it is not the real thing.

Biennale of Art 2024. The 60th International Art Exhibition

Venice, Italy

20 April – 24 November, 2024