The Ural Industrial Biennale: an absolute circus

The Ural Industrial Biennale choice of venue becomes a flashpoint of controversy. The Biennale faces its first stumbling block months before the launch of its 6th edition, after artist Alisa Gorshenina (Alice Hualice) announced her boycott in protest of its association with the Ekaterinburg Circus and the latter’s alleged track record of animal abuse

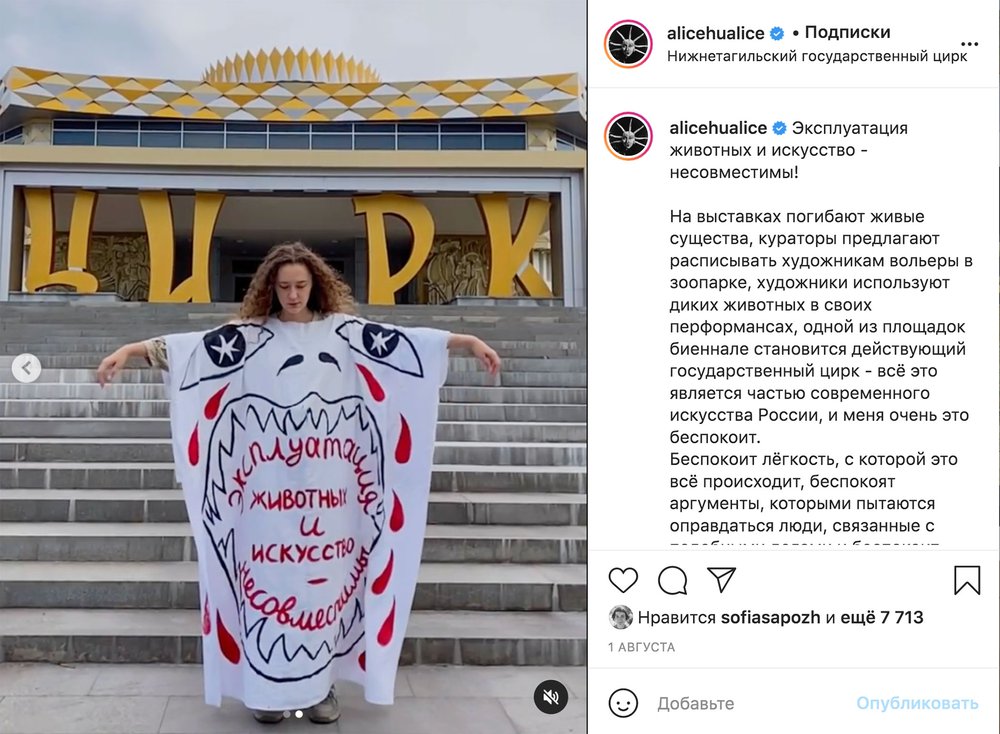

“Animal exploitation and art are incompatible” read Russian letters emblazoned on a white gown worn by Ural artist Alice Gorshenina, also known as Alice Hualice (b. 1994). Behind her, the facade of the state-run circus in her native Nizhny Tagil. Spreading her arms showed the red script was festooned with animal facial features and red tears.

In the caption to this emotive social media post made early in August, Gorshenina recounted the alleged troubling traditions of animal cruelty by Russian state circuses and expressed concern that this institution was being interned into Russian contemporary art. Over the following days, her picket would be replicated by artists and activists in Moscow, St Petersburg, Krasnodar and other cities using the hashtag #циркеннале (roughly, “Circusnale”, a portmanteau of ‘circus’ and ‘biennale’). Soon thereafter, an open letter was penned calling on the Ural Industrial Biennale to remove the Ekaterinburg Circus from its list of venues and launch a roundtable dialogue around the issue of animal abuse in Russian circuses, among other demands. The open letter has garnered nearly 300 signatures as of the time of this writing. Speaking to Russian Art Focus, Alisa Prudnikova, Ural Biennale Commissioner explained the choice of location of the opening: “The circus is part of the concept proposed by the curators of the Biennale Adnan Yildiz, Çagla Ilk and Assaf Kimmel. Doing their research and examining Ekaterinburg through Google Maps, they came across the circus building and got very interested: it is an example of Soviet modernist architecture with a unique dome design. It reminds them of one of Malevich’s ‘planits’, on which the curatorial project is based,” Prudnikova said.

Gorshenina, for her part, had deduced that the choice of the circus as a location for the Biennale likely did not take the question of animal exploitation into consideration.

When asked by Russian Art Focus whether the Ural Industrial Biennale, as one of the larger art institutions in Russia, had the leeway for social commentary on controversial issues, as art often does, Gorshenina showed a dose of Ural pragmatism. “The organizers of the Biennale initially did not even think that cooperation with the circus was a ‘controversial issue’. Apparently, they were simply attracted by the architecture of the space and did not even think about what was happening inside,” Gorshenina said.

The title of the 6th Biennale is ‘A Time to Embrace and to Refrain from Embracing’ and its concept, according to Prudnikova, was devised in the throes of the pandemic and global quarantines. The ideas tackled and, thereupon, locations chosen were made with an entirely human-centric view in mind. “We want to understand the structure of private experience, especially when physical/emotional intimacy is challenged by these dramatic times. Acute questions have arisen: how people feel the boundaries and capabilities of their bodies, how they experience interaction with others,” Prudnikova said. “The curators insisted on revealing the topic through the possibility of creating an individual experience. So trapeze acts became the metaphor for the theme of the main project – Thinking hands touch each other.” Trapeze numbers are but part of the Ekaterinburg Circus’ repertoires. The circus itself makes no secret of its use of a wide variety of animals in its shows. A quick romp through the circus’ online media reveals as much; strewn between images of grand magicians and colourful clowns, videos of bears riding motorcycles and leather-clad performers petting alligators are presented proudly.

In their open letter, Gorshenina and her associates present evidence of systematic mistreatment of these animals. Rosgostsirk, the state enterprise that runs the Ekaterinburg Circus as one of over 40 across Russia, shuffles about 1,500 rare and exotic animals between circuses in what the letter calls a “conveyor belt” system.

“Violence per se and violence against animals are burning issues of our reality and, unfortunately, Russian society is still far from solving them,” Prudnikova said to Russian Art Focus. “Nevertheless, if such a project like ours, which attracts the careful attention of civil society, did not come to the circus, the animal cruelty problem would probably not be that acute now but would continue to exist as we know it.” Gorshenina, on the other hand, regards such a position as disingenuous and merely an afterthought in search of a silver lining. “Perhaps everything would be different if the organizers themselves raised this issue from the very beginning and announced that they were planning it as a critical statement [about animal abuse],” Gorshenina told us. “In fact, it looks as though they only thought about criticism after the public hinted that cooperation with the circus was a troubling undertaking, to say the least.” The young artist similarly took issue with the Biennale’s engagement with those expressing their concern. “They say that they will not change the venue for the Biennale, but they are ready for dialogue. I see a contradiction here, why have dialogue (which, by the way, is still nonexistent), if they immediately make it clear that they will not change anything?” she asked.

The Biennale, however, pointed to the value in the very existence of the controversy. “People started to discuss it more actively, this gives us hope that the problem may be solved sooner than we think,” Prudnikova concluded. The Biennale is set to kick off on October 2 and last until December 5, featuring dozens of artists in three main locations in the capital of the Urals.

The 6th Ural Industrial Biennial of Contemporary Art

Ekaterinburg, Russia

October 2 – December 5, 2021