The Spines of Dissent: A Journey Through A–Ya Magazine

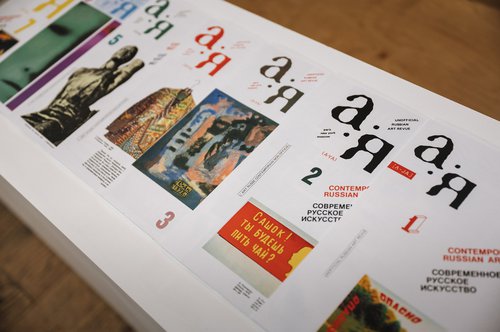

The Path to the Avant-garde: Artists’ Dialogues in ‘A–Ya’ Magazine. Exhibition view. Moscow, 2025. Photo by Daniil Annenkov. Courtesy of Zotov Centre

The exhibition ‘The Path to the Avant-Garde: Artists’ Dialogues in A–Ya Magazine’ has opened at the Zotov Centre in Moscow, immersing visitors in the sharp debates and radical ideas that defined A–Ya, the leading journal of unofficial Soviet art. Russian art critic Sergey Khachaturov explores the fierce polemics—often verging on open insult—that unfolded between editors, artists, and patrons, capturing the spirit of a publication that shaped the history of nonconformist art in the late Soviet era.

A new exhibition in Moscow promises to submerge you in the heated polemics and radical ideas which were at the epicentre of the journal of unofficial Russian art, A–Ya, published in Paris between 1979 and 1984 edited by Igor Shelkovsky (b. 1937) and Alexander Sidorov (1941–2008).

A white ‘cube’ has been built into the rotunda of the Zotov centre, a former bakery factory. However, this is far from a replica of the sterile modernist spaces of Western galleries. This cube is a gigantic magazine rack divided by the spines of the eight issues of ‘A–Ya’ magazine. Each spine represents an individual theme. Brilliantly curated by Anna Zamriy and Irina Gorlova, with a clever design by architects Alexander Brodsky and Natasha Kuzmina, visitors follow a carefully planned route which begins with the ‘Malevich Complex’, reflecting the theme of the first issue of the journal. Here in a programmatic text written by Boris Groys called ‘Moscow Romantic Conceptualism’ unofficial art sits alongside the desire of unofficial artists to come to terms with the accursed, simultaneously unattainable, fetishist legacy of the Russian avant-garde. The exhibition eventually circles back, ending up not on number eight but on another number one, a one off edition which was dedicated the unofficial literary life in the USSR.

Nearly forty museums and private collections have lent works to the exhibition, including the State Russian Museum, the State Tretyakov Gallery, the AZ Museum and some works come from collections of art dealers Alina Pinskaya and Igor Markin.

Guided skilfully by the two curators you literally embark on a journey to the epicentre of what is a very detailed and incongruous biography of this leading émigré publication in which the very first chapter of the history of unofficial Russian art was written.

Irina Gorlova sets the scene from the outset telling us this is not a show about individual artists and heroes of ‘A–Ya’, but about the problem of complex and polemical communication between the first and second avant-gardes, and this polemic runs like a red thread through all issues of the journal. And here is a paradoxical conclusion: standing in front of the first work on display, Kazimir Malevich's (1879–1935) Suprematist Peasant, Gorlova states: “The unofficial artists of the 1970s disliked the avant-garde for many reasons”.

To confirm this, I opened issue number 5 of the 2004 reprint of the journal which was originally published in 1983. It contains an article by Boris Groys ‘Moscow Artists on Malevich’. Here is a quote from it: “The beautiful forms created by the avant-garde seem insipid and boring. They evoke an ironic attitude due to their claim to ‘ultimate perfection’, which contemporary artists are inclined to consider unattainable. At the same time, their alienation and ‘beauty’ deprives them of expressiveness: people are not connected to them vitally and emotionally and therefore cannot ‘express themselves’ through them”.

Here Erik Bulatov (b. 1933) and Oleg Vasiliev (1931–2013) also set forth their own philosophical objections to Malevich, some of whose works were shown for the first time in the flesh at the ‘Moscow–Paris’ exhibition of 1981. Bulatov passes judgement on Malevich’s unwillingness to respect space, collapsing it into elementary objectness. Suprematism, insensitive to the complex empathetic philosophy of painting, became a treasure in the white cubes of museum institutions and commercial art galleries. It exhausted its radical creative revolutionary force and instead turning into a comfortable form of consumer design.

Curiously, Boris Groys gave a name to the alternative to the ‘classical avant-garde’ in this 1983 article. That is ‘transavantgarde’, which is close to the postmodernist idea. The term ‘transavantgarde’ had been introduced in 1979, several years before Groys’s article, by Italian critic Achille Bonito Oliva. Transavantgarde also advocates for a new sensuality, expressiveness, radical voluntarism of artistic statement, a return to traditional techniques, citation, and combinatorics of forms of the present and past.

Perhaps the main achievement of this exhibition at the Zotov Centre is changing the optics on the anthology of unofficial art of the 1970s–1980s. The main focus is not on conceptualism, but the Russian version of transavantgarde as a new eclecticism. Eclecticism is understood not pejoratively, but as an effective method of coupling different vectors of ‘modernity’. The priority of writing and text is questioned for the first time.

Aligning with this heated polemical yet fruitful dialogue with the earlier generation of modernists and with members of their own ‘A–Ya’ fraternity, the movement is constructed in an enfilade of eight parts. Francisco Infante-Arana (b. 1943), Bulatov, Sergey Shablavin (b. 1944), Ivan Chuikov (1935–2020) against Kazimir Malevich (1879–1935), El Lissitzky (1890–1941) and Alexander Rodchenko (1891–1956). There are exceptionally interesting interactions. One just needs recall how Erik Bulatov scraped a tiny point in the middle of the ‘Black Square’, thus liberating the light of space that is blocked in Malevich's world of total objectness.

In the ‘Filonov Mythologeme’ section, there is another trend that I also saw recently in the new exhibition at the State Museum in St Petersburg, ‘Our Avant-garde’. The analytical school of Pavel Filonov (1883–1941) is no longer seen as a group of eccentric outsiders or marginals compared with Malevich, but as an active force with huge resonance in figurative art of the 1960s–1980s. ‘A-Ya’ ideologist Igor Shelkovsky’s mentor Feodor Semyonov-Amursky (1902–1980) is confirmation of this – he enlisted archaism, ancient masks, Eastern art, Egypt and Byzantium as allies in new form-creation. Using analytical means, like Filonov he restored the corpuscular-molecular fabric of life from ruins and fragments, simultaneously acting as an encyclopaedist and a conduit.

And the dense thickets of geometric forms in objects by Igor Shelkovsky reinterpret the organic, and at the same time technogenic mechanics of Filonov’s worlds, seen in a polemical dialogue with Semyonov-Amursky. Within transavantgarde experimentation, Filonov is undoubtedly in a league of his own: the most powerful, sobbing convulsions of Filonov’s expressionist forms become harbingers of today’s art: neural networks, object-oriented art, and net-art. This transition of Filonov’s analytical method to contemporary art is signalled, for example, by objects shown at the exhibition by one of the heroes of ‘A-Ya’: Vladimir Yankilevsky (1938–2018).

Exceptionally precise, though multidirectional parallels are found in sections where unofficial art is compared with the neo-naïve of Mikhail Larionov (1881–1964) and Natalia Goncharova (1881–1962). Mikhail Roginsky’s (1931–2004) ‘Red Door’ is shown opposite a brutal painting by Mikhail Larionov, a composition resembling a triumphal arch, symbolising the victorious return of objectness, or “thingness” in a world of worn-out words.

The dialogues of Mikhail Matyushin’s (1861–1934) optical light-colour and sound experiments with Eduard Gorokhovsky’s (1929–2004) albums and Ivan Chuikov’s paintings are interesting. Moreover, the polemical ardour is obvious. Chuikov, unlike Matyushin, uses chance in his handling of colour: “I simply gave numbers to the paint tins and drew lots from a hat,” writes Chuikov about his 1980 work ‘Window XVIII’, made as a reflection on the theme of Matyushin’s painting ‘Movement in Space’ (1917–1919). “Matyushin specifically studied colour theory, and the selection of paints was very important to him. It seemed to me, however, that the genius of his work was not at all in colour and that colours could be changed randomly without any detriment to the work...”

Such love-hatred permeates the entire space of dialogue between the nonconformists and the avant-gardists. As it turned out, this tension provided charges of the most powerful creative energy for artists of unofficial status. Texts and conceptualism with its hegemony of writing are, of course, also represented. All the more so as an entire issue of ‘A–Ya’ was dedicated to literature. However, even here, the curators cleverly included texts by Dmitry Alexandrovich Prigov (1940–2007) and Lev Rubinstein (1947–2024) in dialogue with the nonsense language of the Futurists, with whom the word first sounded visibly.

The Path to the Avant-garde: Artists’ Dialogues in ‘A–Ya’ Magazine

Moscow, Russia

4 September 2025 – 18 January 2026