The Legend of Till: Remembering Valentin Samarin

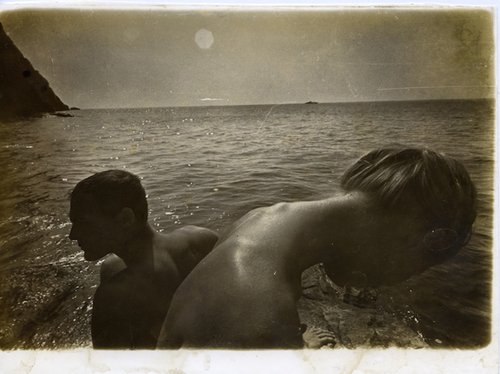

Valentin Samarin. Alexey Khvostenko's metatheater, 1989. Silver-plated paper, sanki print. 25x30 cm. From the collection of Vadim Alekseev. Courtesy of Vadim Alekseev

Till, the last of the Leningrad nonconformist photographers, has died at the age of 96. In the 1970s he was known to the bohemians on the shores of the Neva as Valentin Smirnov. Later while living in Paris, on the banks of the Seine he turned himself into Valentin Maria Till Valgreka Samarin. To his friends he was always just Till.

Till is an ‘excluded classicist’. His work can be found today in the collections of the State Russian Museum in St. Petersburg, the Moscow Museum of Modern Art, the State Yaroslavl Art Museum and the National Library of France in Paris, as well as a dozen more state institutions. Yet Till remains completely unknown to the public at large.

‘The Legend of Till’ was a Soviet multi-part film from 1976. Till Eulenspiegel is a Flemish folk hero who fights a cruel king, the Inquisition and informers. The second part of the film is called ‘Long Live the Beggars!’. In the increasing darkness of the seventies, this film became a metaphor for the struggle for justice and an apologia for poverty. It was not by accident that the name-symbol stuck to Valentin Samarin as ‘Till’ is a rare Russian abbreviation for the name Valentin.

Till began to exhibit in the earliest apartment exhibitions in Leningrad in the 1970s. The first group gathering of the Neva photo underground took place at the flat of the poet Konstantin Kuzminsky in 1974, and Till was already there. From 1978 to 1980 he organised informal meetings, exhibitions, concerts and poetry readings in his flat, in ‘Studio 974’, as he called it, until he was forced to stop these activities after persecution by the authorities. Until the end of his life he remained faithful to the spirit of resistance that had guided him for nearly a century.

Valentin was born in Soviet Leningrad in 1928 just after the 10th anniversary of the October Revolution, and in his childhood he still enjoyed a small glimpse of once Imperial St. Petersburg, a world that was disappearing fast. After school he studied a wide range of subjects in several of the best institutions – at the Maritime School, the Theatre Institute, the Physics Faculty of Leningrad State University and then in the Philosophy Faculty of the same University. Till once told me in a recent discussion that, having fled to Paris in 1981, he was warmly received by the last of the white emigres (post-revolutionary refugees who remembered the Civil War of 1917–1922), who saw in him “one of their own”, the heir of pre-revolutionary culture. He lived in France for a quarter of a century and became a chronicler of Russian bohemia – beggars among beggars, exiles among exiles.

“He was like a flower from another planet,” wrote Dmitry Pilikin, a photographer and curator from St Petersburg who knew Till since the late seventies. In the last years of his life, Till was never seen without his foulard, beret and cane which made him stand out. But Till had been a dandy back in the era when dandyism in the USSR was seen as political provocation: the ‘stylagi’ were one of the main targets of the caricatures of the 1950s.

In the mid-fifties, Valentin took part in public discussions about Picasso's art and for the first time attracted the attention of the KGB. In 1960 he printed and distributed a leaflet ‘For Peace and Democracy!’, after which he was tragically locked up in a psychiatric hospital in a prison, where he learnt the profession of a bookbinder and this is how his journey into art began: with abstract collages made from leftover pieces of paper and paint in the mental hospital on Arsenalnaya Street. In 1981 he was forced to emigrate from the USSR as a political refugee and stripped of his Soviet citizenship.

Till always preferred to be on his own with no family, class, or tribe. During the quarter of a century when he lived in France he changed more than a dozen squats where he worked and often lived. His social housing in Pantin, a suburb of Paris, was like narrow pencil case where you could touch one wall and the other at the same time, most of the space occupied by shelves with his own work. Photographic films were developed in the sink and he slept in a narrow bunk bed built partially hidden under shelves. The flat itself was in a building where some of the flats had burned down, rubbish was thrown into the street out of the windows, and women were never to be seen in the local coffee shop. In 2001 Samarin exhibited his works in the Borei gallery in St. Petersburg, and little by little he began to return to his native homeland. In 2006 he received Russian citizenship, and a few years later he left France and moved back to Russia.

Till was a balletomaniac – an admirer of Maurice Béjart (1927–2007) and Pina Bausch (1940–2009), Roland Petit (1924–2011) and Boris Eifman (b. 1946), whose ballets he photographed. His interest in photography was sparked by Leonid Jakobson's (1904–1975) Leningrad company of ‘choreographic miniatures’, fashionable in the early seventies, with its famous ballet in flesh-coloured tights that made the dancers look like nudes.

Till remained for the rest of his life faithful to the fashion of the seventies, his darkroom experiments using reagents and overlapping negatives, as well as avant-garde filming techniques with sharp camera rotations and changing the perspective of the camera at the point of shooting. He created his own style, recognisable through solarisation and chemical colouring, and called it sanki (a term from a book on ancient Chinese philosophy and meaning “the invisible energy potentials of Time and Space that determine our earthly existence”). But sanki was more than just a style to him.

“Sanki is the universal standing and shining and gaping of time and space,” wrote Valentin Samarin. To justify this universal concept, its interpreters drew on the mathematician Abraham Robinson's theory of non-standard analysis and Etienne Gilson's philosophy of uniqueness. Sanki are unique objects arising from the process of their photographic expression, the refraction of the wide world in each of them. In his theories, Valentin Samarin remained faithful to the supersensual pursuits of the Russian avant-garde.

Till was a photographer of underground life in Leningrad and Paris for half a century, but by no means its chronicler. Till's style can be called consistently anti-documentary. He was not interested in the ‘photo-fact’ as much as a breakthrough into another reality through artistic events, that is, not in the physical but in the metaphysical dimension of photography and the ability of the silver print to be a medium, to demonstrate “the oneness and mystery of every human presence”. The chemicals themselves were as important to him as the subject. Photography for him was not something that melds (according to Roland Barthes) with reality, but a way of generating unique objects that testify to the energies that permeate all things.

His portraits are dedicated to the people he saw as guides notably the poet Joseph Brodsky (1940–1996), ballerina Maya Plisetskaya (1925–2015), artist Oleg Tselkov (1934–2021) and the cellist Mstislav Rostropovich (1927–2007). He was not interested in ‘famous names’, but in that psychic substance which can be called ‘charisma’ – cabaret singer Natasha Medvedeva (1958–2003) and the underground bard Alexei Khvostenko (1940–2004) were among his favourite heroes. Till considered aura as a physical phenomenon, which can be shown with the help of photography.

Till's favourite themes were sex, death and magic as seen in ballet and the performing arts, such as Boris Eifman’s Satan’s Ball or Philippe Tallard’s Stairway to Heaven. Mstislav Rostropovich playing at Andrei Tarkovsky’s memorial service. Alexei Khvostenko’s ‘metatheatre’ – from his performances in Parisian squats to Khvostenko’s own funeral at Skhodnya railway station near Moscow.

Till could be called the ‘excluded from the excluded’ as despite the fact that he was well known to all those who were at least tangentially involved in the cultural history of Leningrad-St Petersburg over the last half-century, his works have not been collected by influential collectors, and today art historians and curators in the Russian Museum are barely aware of his existence. In the recently published ‘The Oxford Handbook of Soviet Underground Culture’, a chapter on the Leningrad photographic underground mentions him briefly in passing as the only living member of the underground (at the time of the book's publication). This unvarnished figure, difficult to fit into pre-arranged discursive ranks is a kind of headache even for the most earnest of researchers.

Till's style could be described as neo-conservative avant-garde. It is quite typical of Leningrad-St Petersburg artists to think that beauty exists only somewhere in the past or in parallel a universe, but that is no reason not to have some fun in the meantime. A magazine with a tiny circulation of dedicated followers that he and his friends published in Paris in the early 1980s was called ‘Back’.