The Brotherhood of New Blockheads: Marginal Legacy Revisited in Berlin

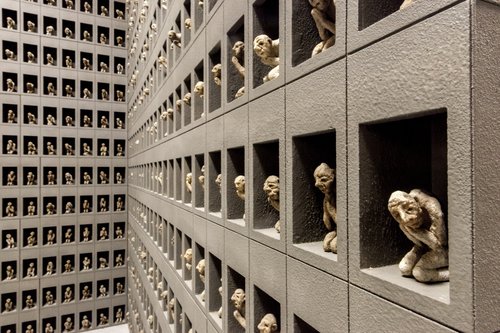

The Brotherhood of New Blockheads. Inner Eroticism / Central Russian Elevated Stupidity project, 2000. Courtesy of Dmitry Mikhailov and Oleg Shagapov

TNT was a group of rebellious performance artists that had its heyday in the late 1990s in St. Petersburg and now is the subject of an archival exhibition in Berlin’s BQ Gallery. Artist Dmitry Vilensky is based today in Hamburg but was born in St Petersburg and witnessed first-hand its short-lived yet memorable career and reflects on new meanings in their ephemeral art in our changing social and cultural context.

Formed in April 1996 at the Borey Gallery in St. Petersburg, The Brotherhood of New Blockheads (Tovarishchestvo Novye Tupye, TNT) emerged as a radical and absurdist artist collective that viewed life itself as a performance. Drawing inspiration from the avant-garde poetics of the Russian OBERIU group and contemporary philosophy, the The Brotherhood of New Blockheads brought a spontaneous, anti-hierarchical approach to art-making and public action.

Their motto “Long live all creatures!” (1997) encapsulated a worldview grounded in humanism, irony, and anarchic freedom. TNT’s members including Vadim Flyagin (b. 1958), Igor Panin (b. 1961), Sergey Spirikhin (b. 1963), Inga Nagel, Vladimir Kozin (b. 1953), Maksim Rayskin (b. 1970, Oleg Khvostov (b. 1972), and Alexander Lyashko (b. 1965) eschewed fixed artistic roles, instead merging sculpture, literature, philosophy, and performance into a unified field of aesthetic experience.

At first glance, the group’s carnivalesque actions and deliberately “foolish” persona might appear to place them in a lineage of jesters or pranksters, echoes of Russia’s cultural traditions of holy foolishness (yurodstvo) and Petersburg absurdism. Yet beneath this mask of idiocy lay a sharp critique of the social and cultural disorientation of post-Soviet life.

As Igor Panin put it: “A stupid life gives rise to a stupid gaze, a stupid gaze produces stupid art — and that is already harmony.”

Between 1996 and 2002 when they disbanded, TNT created more than seventy actions and performances often spontaneous, undocumented, and radically ephemeral. In revisiting their legacy nearly two decades later, their practice stands not only as a document of its time but also as a prescient refusal of institutional logic and aesthetic predictability.

As an artist who grew up in the same environment as the New Blockheads (TNT), and who had direct involvement in the publication of their programmatic magazine Maximka, it is interesting for me to try to understand how it is possible – and how it happens – that certain marginal historical phenomena are integrated into the contemporary context, and how the translation of artists’ works from one context to another is possible. How are TNT's works perceived today in Berlin and how did they get there?

It must be said that they ended up there by happy accident: according to the exhibition’s curator Daniel Baumann (Director of Kunsthalle Zürich), the GQ Gallery in Berlin was looking for something “totally crazy” during Berlin Art Week – and this totally crazy thing turned out to be in Daniel’s basement in the form of a packed-up exhibition that had taken place at Kunsthalle Zürich in 2019, and in a much-reduced version, it found itself at the epicenter of Berlin gallery life, at the main event of the season, in front of thousands of art professionals.

At the exhibition, there is a generous selection of various TNT performance videos, made throughout their creative period, shown in a cinema style room inside the gallery. On a separate projection, viewers see an iconic performance by Vadim Flyagin, Vanka-Vstanka, where the performer, over several hours, falls down and gets up from four chairs. This is a classic example of endurance performance, and a perfect merging of life and art: the artist literally slept on those same four chairs for several years in the storeroom of Borey Gallery, where he worked as a cleaner. Also featured in the exhibition are reconstructed TNT installations and autonomous series of graphic works by Inga Nagel and Vadim Flyagin, hanging salon-style across two large gallery walls. And, of course, many brilliant photographic documentations of different performances.

I visited the exhibition both on the opening night and the day after mostly to observe the reactions of the audience rather than the works themselves, which were already familiar to me in many ways – although the Swiss and German production capabilities significantly transformed the works themselves. The death of the artist (and the TNT phenomenon clearly falls into that category, even though most of its participants are still alive) always opens up the possibility of endless speculation about their legacy – especially when it comes to serial works and potential protocol-based reconstructions. That is why many historical exhibitions look so fresh and impressive today: thanks to the possibilities of digital enlargement and photo processing, incredible projection technology, spatial design – all of which refresh and transform historical works and, in many ways, make them contemporary.

The New Blockheads were very lucky to have worked with top-notch local photographers (Sergei Lyashko, Oleg Shagapov), who managed to create truly iconic images, often resembling classic performance photography of the 1960s and 1970s. Shot in black-and-white and aged colour tones, they create even more confusion when viewing TNT’s art: when was this made? and where? The Russian context – or more precisely, the context of the St. Petersburg art scene – is completely unfamiliar to Western audiences, and most international curators would hardly be able to recall even a few key names from our milieu. And this situation flattens the perception of TNT’s works, which arose in direct confrontation with the fascistoid pseudo-intellectual kitsch of the ¨New Academy,” the beginnings of the media art boom, and St. Petersburg dandyism and trendiness. At the same time, they drew upon a very important tradition of absurdism in Petersburg culture (OBERIU), and perhaps it is this tendency that makes their art so relevant and in tune with our crazy times.

Another unexpected coincidence: the TNT exhibition ended up being next door to a solo exhibition by Nadya Tolokonnikova (b. 1989), which inevitably led to comparisons. The context of Pussy Riot, the most well-known cultural-political phenomenon from Russia, is of course familiar to everyone, as a kind of pop phenomenon. But when translated into the language of contemporary art, it becomes a rather banal, albeit well-executed aesthetic statement – which, strangely, has little to do with the raw energy of the historic performances of its time, and is immediately transformed into consumerized, normative production. In contrast, the New Blockheads – against the backdrop of an apolitical contemporary art scene in Russia – were not afraid to respond to political events, always finding a poetic language in which to do so: their response to the war in Chechnya was the performance ´Laundry Day´ – washing the Russian flag as an attempt to wash away shame; their response to the war in Yugoslavia was ´Slavic Bazaar´ – pouring bloody borscht not into bowls, but onto a white tablecloth. This political stance now seems more complex, more artistic, than the rhetorical moralizing of Tolokonnikova’s installation ´Have You Ever Fucked the System?´ In their own register, TNT were always doing just that - they genuinely didn’t care about the system, and the system didn’t care about them.

And this authenticity turned out to be the hook – as was immediately visible from most reactions and small talks – that captivated even the most sophisticated international audience. It’s also worth considering that there is growing fatigue with the endless conveyor belt of perfectly executed, conceptual, minimalist, politically correct art – and the viewer, on a gut level, felt a forgotten sense of freedom, poetry, unpredictable and intriguing references.

It’s important to say again: today’s interest is not related to the exoticism of the material (as critics of the time often emphasized when analyzing TNT’s work), but rather to a sense of recognition: TNT’s imagery feels surprisingly familiar – in the context of punk, squats, the cult of poverty (especially resonant in Berlin), and, of course, everyone has their own “wild,” dumb, weird ones. One visitor, critic Raimar Stange, told me that at that time, all art academy students lived more or less the same way and made more or less the same kind of art. I don’t fully agree with this view, but I do agree that TNT’s work involved simple entry points of recognition (as has always been the case, for example, with Moscow Conceptualism), and when those are combined with a lasting nostalgia for authentic experience, the phenomenon of the unrecognized genius (“Van Gogh” – another St. Peterburg artist and curator Pyotr Bely (b. 1971) called TNT the “Van Goghs of performance”), and a light exotic flair (after three years of fighting in Ukraine, few people are scandalized by Russian origins), the result is a striking and attractive story. Will there be a continuation of that story? Unlikely. But just like this exhibition – and the state of the world in general – it’s best to leave room for miracles.

And the New Blockheads deserve one.