The Blunt Tool of Labelling Artists

Ilya Repin. Reply of the Zaporozhian Cossacks, 1880–1891. Oil on canvas. Courtesy of State Russian Museum

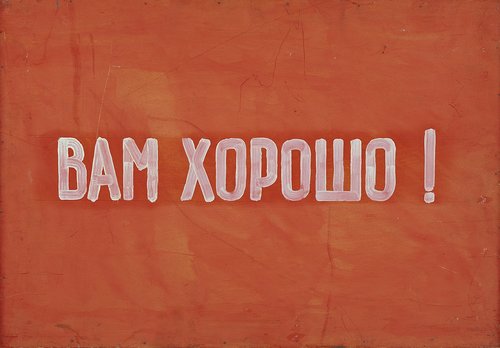

The conflict between Russia and Ukraine has sharpened sensibilities and focussed new attention on how museums and art portals categorise artists in terms of their nationality. How do we find a balance in the crossfire of vested political interests?

Culture is under fire. Over the past year there have been numerous cases of Russian heritage being cancelled from museums and concert programmes across Europe and North America. Now the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, ostensibly reacting to pressure from comments on social media, has raised eyebrows by re-classifying three artists in its holdings - Ilya Repin (1844–1930), Ivan Aivazovsky (1817–1900) and Arkhip Kuindzhi (1842–1910) - as Ukrainian.

A cursory search on the MET’s website in fact quickly reveals shortcomings and inconsistencies in how artist nationalities are described there in general. Louise Bourgeois, born and studied in France and emigrated to the USA when she was 27, is described exclusively as ‘American’. Although Anish Kapoor was born in India, he is described only as ‘British’. Chagall is ‘French’, and so on. Although all three of these artists assimilated themselves into their adopted countries and officially took on new nationalities, this blunt way of labelling them evades their true origins.

Comparing the MET’s approach with other world-class museums it is less inclusive than its peers. As a standard today among the international museum community it has become more common to reflect both the place or nation of birth and the adopted country for artists who have moved abroad either for a substantial part of their careers or who settled abroad indefinitely. At MOMA they note the birth places of artists immediately after their nationality, a helpful approach for artists who have emigrated. Chagall is here described as ‘French, born Belarus’. But there are also glaring mistakes commonplace across all such globally-minded art institutions. Just one example: Ilya Kabakov who was born in Dnipropetrovsk in Ukraine, is incorrectly described on MOMA’s website as ‘American, born Russia 1933’. Among the leading state art institutions, the Centre Pompidou in Paris seems the most conscientious at actively describing artists’ origins and their nationhood. Further, they also take care to use the term the ‘Russian Empire’, rather than ‘Russia’ when referring to country of birth.

So, even with these more inclusive approaches, categorising artists by nationality or birth is a minefield, and some museums understandably try to avoid doing it at all. At Tate they sidestep, defer to Wikipedia and lift artist biographies directly from there, pasting them into their website rather than having them written by inhouse staffers. When categorising artists by nationality, Wikipedia takes an inclusive approach in general, preferring not to omit one nationality over another, reflecting both by way of a hyphen, hence Bourgeois is ‘French-American’ and Kapoor ‘British-Indian’. But with artists from the Russian Empire, they are described as ‘Russian’ such as in the case of Chagall who is described as ‘Russian-French’, for example, and Malevich is outright a ‘Russian artist’ with no immediate alternative definition of his nuanced cultural origins.

Looking at these global standards, none is perfect nor followed to the letter, however, it is disappointing that the MET did not take a more inclusive and balanced approach when considering how to define the nationality of all three artists (not to speak of Bourgeois and Kapoor!). In fact, they have allowed for national duality in their description of artist Josef Albers who is described as ‘American, German-born’, showing their exclusive approach is not set in stone.

But all this discussion precludes the biggest point here about Ilya Repin and Arkhip Kuindzhi in particular: the bluntness of a tool which serves to obscure often national or cultural identities which artists themselves relate or belong to, sometimes by choice, and not to speak of ethnicity. To define them exclusively as Ukrainian and not mention Russia, is essentially taking them out of the real context within which they lived out their professional lives. It seems like an act of rewriting history.

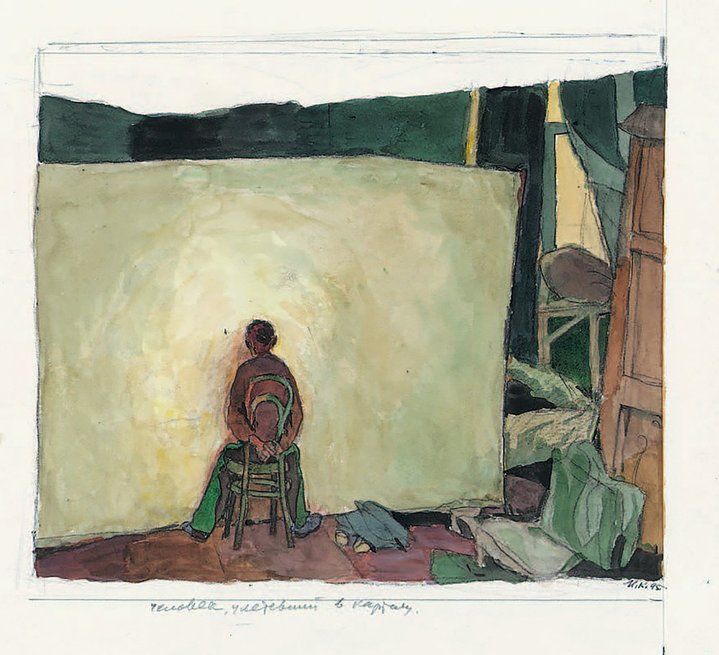

From the age of nineteen, Ilya Repin, studied then worked and lived in Russia - the country as well as the Empire. Although he was born in Chuhuiv in Ukraine he did not need to change his nationality to reflect moving from one corner of the vast Russian Empire to another. Repin spoke both Ukrainian and Russian fluently, and he considered himself a Russian, at the same time holding deep affection for Ukrainian Cossack culture. Thus, to reflect his origins and his place in both the interdependent cultures of Russia and the Ukraine (also under the umbrella of the Empire) and contribution to Russian 19th century culture, it would be far better to classify him as a ‘Ukrainian-born Russian artist’.

Similarly, Arkhip Kuindzhi moved to St Petersburg when he was in his 20s, and like Repin became a defining force in the creation of the Russian realist school, and the Peredvizhniki. Both taught for many years at the St. Petersburg Academy of Arts, where they had studied and for all intents and purposes they had moved to Russia and their careers and lives were intimately connected with the artistic life of Moscow and St Petersburg. Yet Arkhip Kuindzhi’s art is one long, lyrical song to the Ukrainian landscape, and some of Repin’s greatest works are about the Zaporozhian Cossacks of the Ukraine, part of a rich body of work he produced about the country of his birth.

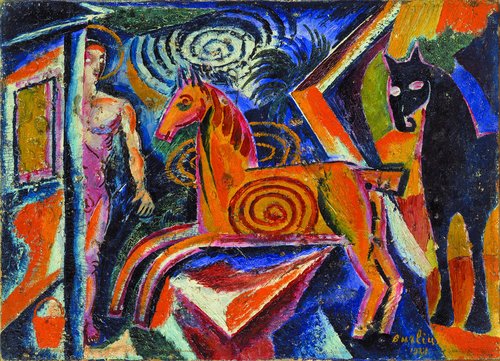

Marine painter Ivan Aivazovsky – born Hovhannes Aivazian - perhaps defies being put in a box more than any other 19th century artist I can think of, and it is hard to exaggerate this point. He has been claimed variously as the cultural heritage of Russia, Armenia, Ukraine (and even Turkey!). To Anton Chekhov the master of the pithy, Aivazovsky was an Armenian and currently the global art portal Artnet refers to Aivazovsky as an Armenian-Russian artist, although he was not actually born in Armenia and never lived there. Unlike Repin or Kuindzhi who did move to St Petersburg (or in the case of Repin also Moscow) and became a part of the artistic life of Russia, Aivazovsky chose to live in the town of his birth, Feodosia, in the Crimea which was an independent khanate until the 18th century when it became part of the Russian Empire, remaining a part of Russia until the mid 1950s.

Errors and inconsistencies aside, the re-classification of these three artists by a top Western museum comes across as a politically motivated act, such are the times we are living in. Yet looking at the bigger picture where key information about artists is decided and recorded in all our biggest state museums in Europe and North America and served to the public, one is left wondering whether globalism itself, which is already a few decades old, has failed us even on the most basic of levels.