The alchemy of glass

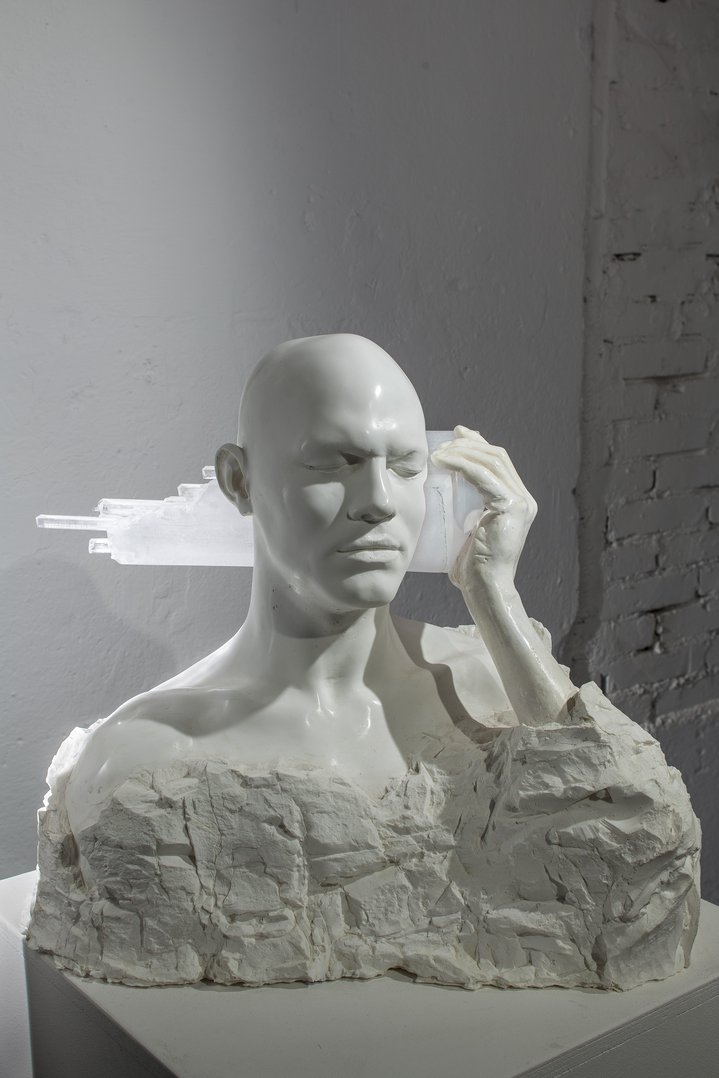

Ilya and Emilia Kabakov. Arch of Life. 2015

The footprints left by Russian artists using one of the world’s oldest techniques in the Venice lagoon.

Like pilgrims to a shrine, a group of artists have returned to the island of Murano during the 58th Venice Biennale to cast in glass what their imaginations have conceived. The Glasstress project, which celebrates its 10th anniversary this year, represents a marriage of contemporary art with a process whose technology has remained unchanged since the Middle Ages, except that gas has replaced wood to stoke the fire in the furnaces.

It was the long-time Venice resident and collector Peggy Guggenheim (1898–1979) who promoted that artistic fusion, was inspired by the work of Venice’s masterly glassmaker Egidio Costantini (1912–2007) who had shown artists such as Jean Arp, Alexander Calder, Max Ernst, Pablo Picasso and others how to transform their work into glass sculptures.

The idea was revived as the Glasstress project in 2009 by the entrepreneur Adriano Berengo who had set up his glass studio in Murano 20 years earlier. Over 200 artists of various disciplines have since taken part. They include China’s Ai Weiwei, British architect of Iraqi origin Zaha Hadid and Belgium’s Jan Fabre as well as an active Russian contingent.

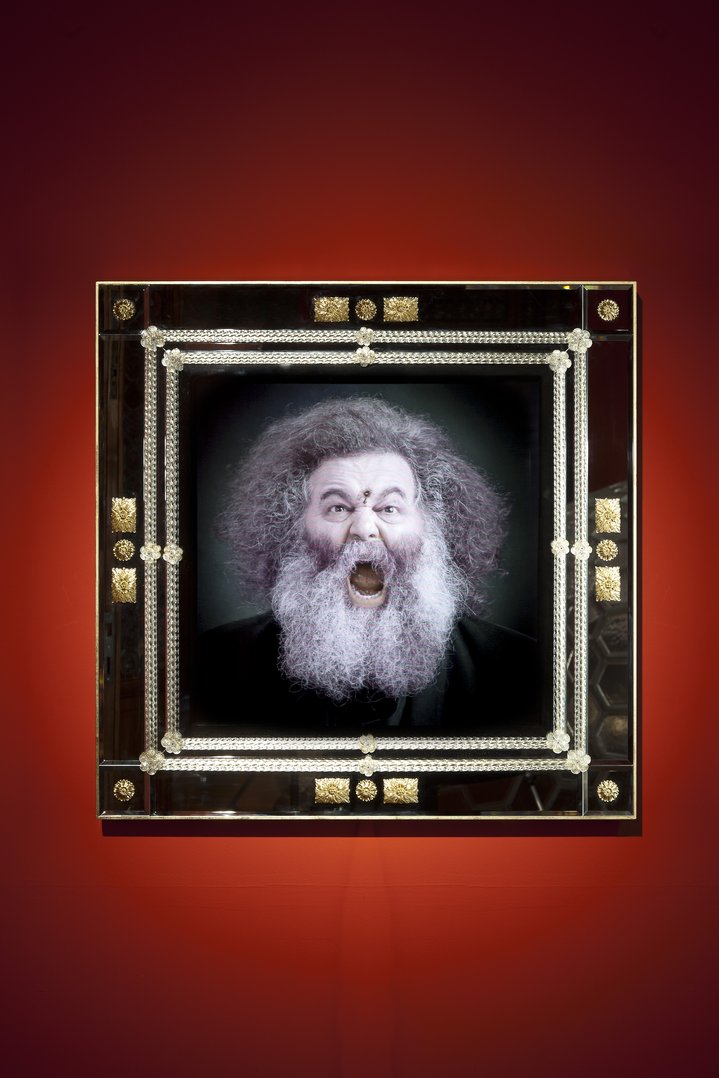

Oleg Kulik's work was placed on a remote part of an abandoned glass works on Murano. The artist interpreted this as putting his creation into "exile."

Russia’s Ilya and Emilia Kabakov have returned to Glasstress for the third time, after 2013 and 2015. Their sculpture “Arch of Life,” created in 2015, is now on show again.

Curators along with Berengo supported the work of the Moscow-based artist Oleg Kulik, who in 2011 created a glass statement called “Basta Carne” (No more meat) in support of Ai Weiwei, who had been arrested in China shortly before the opening of that year’s Biennale.

In it, Ai Weiwei appeared in a Buddha posture representing the artist’s spirituality, while the body of another Chinese artist, Zhang Huan, was covered in meat as a symbol of materialism and the commercial aspect of art. Zhang Huan was one of the 2011 Glasstress artists and a prominent exhibitor at that Biennale.

Kulik’s work was placed on a remote part of what had been an abandoned glass works on Murano (now the Berengo Foudation Art Space). The Russian artist interpreted this as putting his creation into “exile.”

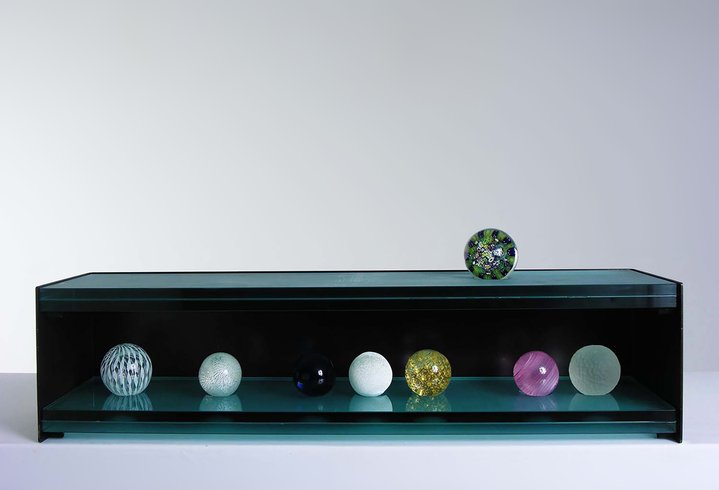

Russia’s Dmitri Gutov caused a different problem in 2013. He originally wanted to create a large pond with stones. However, the required size was too big for glass. As glass and stones cool at different speeds, inserting them into glass was also a challenge. In the end, stones were pressed in hot glass to form a mold, but it still took a lot of work to make them fit in.

Russian artists’ interest in Murano glass began four years before Glasstress had even been created when three Moscow artists — Nikita Alexeev, Sergei Mironenko and Andrey Filippov — benefited from a residency in the Berengo studio and created several works in glass.

The following year, Moscow’s State Pushkin Museum of Fine Art staged an exhibition called “Handle with Care,” featuring the works of the three Russian artists as well as those of 12 international artists who were then working at the Berengo studio.

It is easy to be surprised and charmed by glass, as well as annoyed by its kitsch. The border that separates them is very thin. Today, it is the boldness and imaginative spirit of contemporary art that makes the difference.