Sergei Borisov: looking back anew

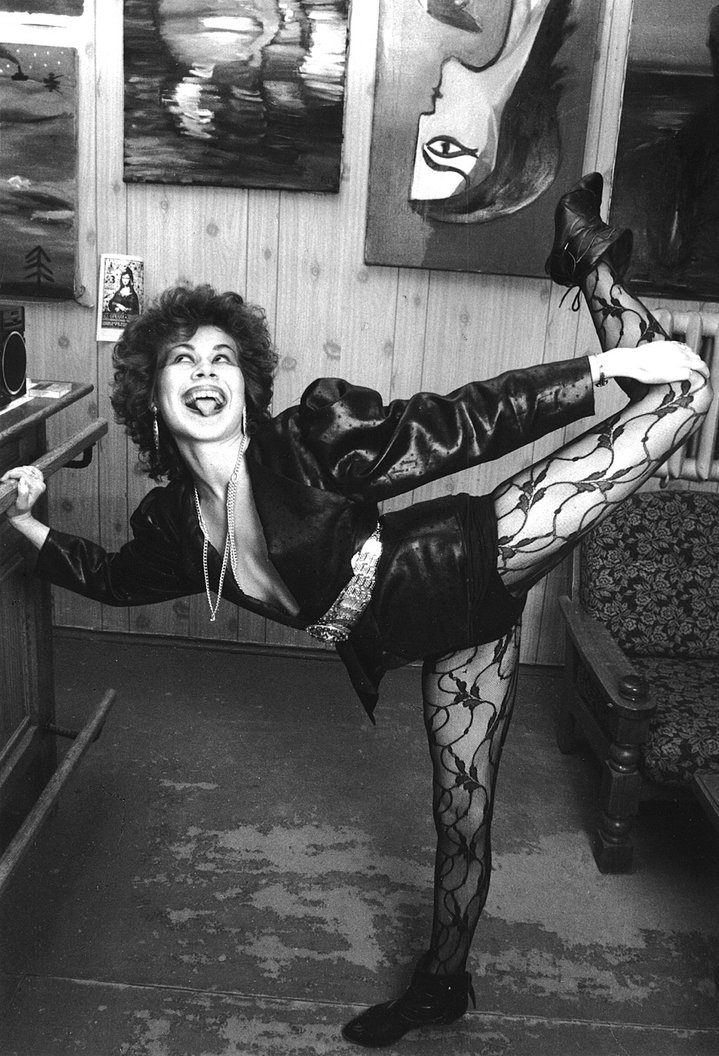

Sergei Borisov. Flight, 1988. New meanings. Courtesy Ruarts gallery

Sergei Borisov, a tireless chronicler of Russian underground culture, is revisiting his own now-classical works of the 1980s in a new photo project due to be shown at Moscow’s Ruarts gallery.

While Moscow and Leningrad in the 1980s were unraveling into political chaos, Soviet counter-culture was bursting open. Thanks to the freedoms permitted by perestroika and glasnost, access to once forbidden fruits, such as political protest, international collaborations, American jeans, punk and rock music, among others, injected a febrile atmosphere into a society that was overhauling itself. “Tusovki” were the unusual and arresting (often literally) gigs, happenings, and exhibitions where the risk-taking subset of that young Soviet generation thrived, and Sergei Borisov (b. 1947) became their photo booth.

If all goes well on the epidemic front by then, a selection of Borisov’s recent photographs will be exhibited alongside his now-iconic images from the last two decades of the past century at Moscow’s Ruarts gallery from April 15 to May 31. His ‘New Meanings’ exhibition is structured around pairings of old and new images, where the latter one replays a scene, place, or gesture of the earlier one. Borisov has called this process “self-citation”, although he emphasizes that the concept emerged organically rather than in a self-conscious way. “It all started by itself. I just liked some subjects and I involuntarily repeated them. The first time I deliberately quoted myself was in 2014 with the photograph of a girl and an oar. However, this was more me referencing a common subject than making an explicit self-citation.” He also does not consider the project nostalgic: “There is a living underground now; we don’t need to get hung up on the past.”

Born in 1947, Borisov showed early interest in photography. He joined the photo club at the Moscow House of Pioneers at age 12. By 1976, he was photographing Soviet actors and musicians, creating images for concert posters and album covers that would transform them into pop stars. Simultaneously, Borisov entwined himself in the wild, messy, and very special side of Moscow, building friendships with artists Ilya Kabakov (b. 1933), Vladimir Nemukhin (1925–2016), and Anatoly Zverev (1931–1986).

Around 1979, he turned his personal studio on Znamenka streeet into a stage. ‘Studio 50A’, as it came to be called, hosted exhibitions and performances, ranging from local groups to underground stars like the late Viktor Tsoi and Pyotr Mamonov. Borisov’s photographs of Studio 50A elevated the edgy and the weird and in doing so attracted the attention of Soviet sanitation officials, as well as foreign fashion glossies. In his images of the Leningrad rock scene for Le Monde in 1984, undernourished men in leather jackets and women with matching metallic jewelry and dyed hair gazed at the world in a variety of styled and straightforward poses. Marrying rugged subterranean culture with cosmopolitan chic, those photographs razed through Europe and the United States.

Like many of Borisov’s photographs, the visual interest arises from the tension between the eternal and the ephemeral. A gesture like a jump against the pull of gravity or a breeze catching a skirt makes viewers aware of time’s suspension in the photograph.

But Borisov plays with time in other ways. He recycles not only key formal properties, but also material ones. For instance, though he used different cameras, he shot all the images on black-and-white film. Thus, the exhibited photographs can be read from left to right or right to left, defying temporal order. This fantasy of the reversibility of time may work to superimpose a spirit of perestroika on present-day Moscow.