Russian art in Venice: between circus and pathos

Alterazioni Video. The New Circus Event. Photo by Ekaterina Wagner

Russian art institutions flaunt their larger-than-life ambitions at the Venice Biennale.

A female acrobat was striking posed atop an old plush chair; a washing machine shook and jumped violently inside an iron cage; a man in a tuxedo was making and giving out sugar-floss to anybody who wanted it; an excavator positioned on a barge moored at the Zattere embankment was scooping water out of the lagoon and pouring it back. The delightfully absurd freak show, which involved both professional and amateur artists, was called The New Circus Event. It was a gift to the residents and visitors of Venice from the V-A-C Foundation, a Russian institution that has a venue in this Italian city, but none yet in Moscow (the enormous exhibition venue in the Russian capital is scheduled to open in 2020). The private institution is funded by gas tycoon Leonid Mikhelson — Russia’s richest businessman, according to Forbes magazine. The show (which, regrettably, lasted only for the duration of the Biennale’s preview days) was probably Russia’s most colourful contribution to the world’s biggest art event. Ironically, the performance, organized by the international collective Alterazioni Video, had just a few Russians participants, including the artist Petr Bystrov, who was laboriously drawing his own versions of banknotes given to him by generous spectators — or even those who were not-so-generous: I gave Bystrov only 100 roubles (about 1.5 US dollars) and walked away with the drawing, before realising it was not quite a fair exchange. The spirit of the show was not alien to the Russian mind, though. The absurd is a driving force in Russian reality and could have easily become the country’s most popular export product, after oil and gas. It's not for nothing that “Meanwhile in Russia” memes have inundated the web. The circus bacchanalia was a welcome respite from the deadly serious exhibition located within the walls of the V-A-C institution itself, called “Time, Ahead!” and showing conceptually complex and technically advanced site-specific installations by Russian and international artists.

Contemporary art is not at all opposed to the absurd, and neither is the Biennale’s jury. Its experts granted the Golden Lion, the Biennale’s top award, to the Lithuanian pavilion, where an opera is performed by semi-naked singers on an artificial indoor beach. The project by artists Lina Lapelyte, Vaiva Grainyte and Rugile Barzdziukaite addresses the issue of climate change. Gravity and nonsense merge together in perfect harmony. However, in the Russian national pavilion in the Giardini, pathos and circus co-exist within the same building in obvious discord, like quarrelling neighbours in a Soviet communal flat. The main topic of the exhibition is not a current social or cultural issue, but the Hermitage museum itself. The museum, housed in the former imperial palace in St. Petersburg, is renowned worldwide for its collection of Western art. The Russian pavilion’s installation on the top floor, conceived by film director Alexander Sokurov, is dark and solemn. It features sculptures based on the Rembrandt’s “Prodigal Son” (one of the Hermitage collection’s highlights) and two enlarged copies of other Rembrandt works. These are complemented by two equally grim videos, full of fire and destruction and occasional appearances of a seated Christ in the desert. This is based on a painting by the Russian 19th century artist Ivan Kramskoy. This nearly indigestible mix leaves the viewer more bewildered rather than moved. The lower floor is lit by ominous red lights. Here the absurd side takes over in a kinetic installation by St. Petersburg artist and theatre designer Alexander Shishkin-Hokusai (profiled in the April issue of Russian Art Focus). Plywood renderings of Flemish old masters’ paintings from the Hermitage move along the walls, while plywood spectators perform a nonsensical mechanical ballet. This absurd museum where nothing is either stable or authentic could have been a rather witty parody of any large institution (or even a very big country) if it occupied the whole building, rather than just the Russian Pavilion’s claustrophobic lower half. As it is, it feels trampled by the weight of its upstairs neighbour’s larger-than-life ambitions. At least it’s fun to watch.

An excess of ambition and lack of big ideas seems to be the curse of Russian shows in Venice this year. Or is it just the curse of great state museums, which are more used to conservation than experimentation and tend to look back to the past rather than face the present, much less dream of the future? The State Tretyakov Gallery brought a solo show of Gely Korzhev (1928-2012) to the city. This Soviet realist painter outlived his time and bemoaned the collapse of Socialism. In his late paintings, resurrected skeletons and horror movie-style monsters act as symbols of the new political reality. The project “There is a beginning in the end,” organised by the State Pushkin Museum and supported by Moscow’s Stella Art Foundation, is dedicated to Tintoretto, and even includes his newly restored work “The Origins of Love,” loaned by Venetian art dealer Pietro Scarpa. (Most people who come to Venice definitely want to see some Tintoretto. That’s why including him in the exhibition is always a smart move, if not too new one. Bice Kuriger, curator of the 54th Biennale, displayed three of his paintings in her main project in 2011, so why not follow a good example?) Three site-specific video installations by Russian theatre director and designer Dmitry Krymov, renowned Moscow conceptualist Irina Nakhova and American artist Gary Hill are all visually striking and work well with classical architecture of the San Fantin church. Yet they are screened one after another and the whole show lasts an hour. First comes Krymov’s piece, where the transition from circus to pathos is probably most rapid. Those who walked in during its engaging and playful opening have to endure a seemingly endless finale before they can enjoy the stunning imagery of Nakhova, or Gary Hill’s mesmerizing digital abstractions.

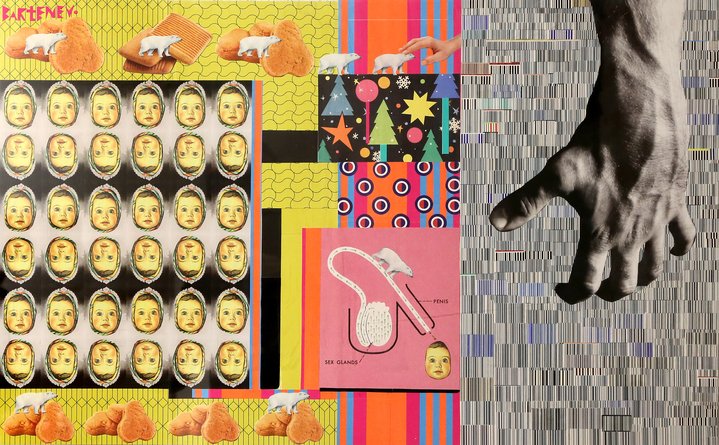

Does it mean that there is no happy medium for Russian art? Certainly not. Curators of at least one exhibition in Venice somehow managed to walk this fine line. It lurks deep within Ca’ Foscari University’s library and, characteristically, has no obvious connection with either the state or oligarchs. A show called Id. Art:Tech brings together works of international and Russian (mostly St. Petersburg) artists dedicated to the notion of the self in the digital era and the era that came before it. Works by Erik Bulatov, Oleg Vassiliev, Vagrich Bakhchanyan and other heroes of the pre-iPhone age are juxtaposed with Marina Alexeeva’s witty animations projected on a fountain of chocolate, Ludmila Belova’s striking photos of used beauty mud-packs, Andrey Bartenev’s colourful collages, Alexandra Dementieva’s underwater videos and other artists’ reflections on the subject. Apparently, it is still possible to put together an interesting show without the help of Rembrandt and Tintoretto. Sounds reassuring, no?