Robert Falk: a painterly alchemy

The State Tretyakov Gallery will stage a retrospective of this artist who found his own distinctive style after bringing together elements of Cezanne and the Russian Avant-Garde. In the process he managed to become the mentor of a whole generation of Russian artists. His show is due to open in January, once the pandemic restrictions in Moscow are lifted.

“My misfortune is that I am an artist,” Robert Falk (1886–1958) once proclaimed, as quoted in Anton Uspensky’s recently published monograph, ‘Robert Falk: Schastye Zhivopistsa’ (“Robert Falk: The Joy of Painting”). It expresses both the burden of his painting and the bittersweet taste of his vocation. His exceptionally charged canvasses bear witness to a life’s calling fulfilled to the utmost: colossal in their representational exactitude and humble in the ephemeral mid-tones of grey, they capture with such poignance – speaking of something much bigger than themselves and, at the same time, nothing at all. A late still life channels the main arteries of Falk’s art and life: ‘Potatoes’ (1955), the most modest subject matter, executed in a palette of brownish greys, the essence of scarcity and humility. And yet, it shimmers with light, a barely noticeable flicker of red or blue, bringing the whole image to a poignant tension. The result is painterly alchemy. “I may be a bad artist, but I will be an artist and only that.” That is what the young Falk said when deciding to pursue his artistic education, despite the opposition of his middle-class Jewish family, which dreamt of a more respectable career.

Before the 1917 Russian Revolution, he studied in Moscow’s leading ‘School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture’. It was there he befriended a generation of young artists, who became the founding members of the Avant-Gardist ‘Bubnovy Valet’ (“Jack of Diamonds”) art group. Inspired by the newest art in France, its goal was to break free from academic painting.

After the revolution, Falk joined renowned artists in steering the new revolutionary Vkhutemas art school and headed the painting department of this “Soviet Bauhaus”.

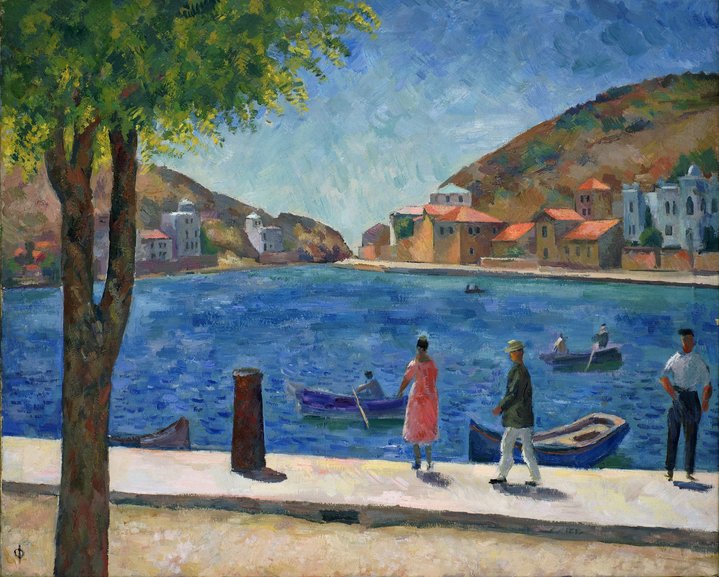

However, he is already becoming a self-professed realist and, thus, steering away from many of his more radical colleagues. Realism in him is not a superficial likeness of representation, but the translation of true life into canvas. In this, he saw Cezanne as a beacon. He was hugely indebted not only to Cezanne. He also borrowed from a whole host of predecessors and contemporaries, ranging from Rembrandt to Impressionism, Art Nouveau, Fauvism, Neo-Primitivism and Cubism. However, he never fully embraced any one of them. Instead, he co-opted them to serve his artistic purposes, his inherent trajectory towards painterly realism. One of his most famous works ‘Red Furniture’ (1920) dates from what Falk saw as his most successful period. One can see the exaggerated angularity and broken planes of Cubism, the bold colour of Fauvism, even Impressionistic brushstrokes and yet there is a direct connection to the humble potatoes 35 years later. In 1928, Falk travelled to Paris for an ostensibly short work trip and stayed 10 years. That pilgrim went to the artistic Mecca not only for inspiration, but also to find shelter. He felt tugged in too many directions and suffered from his own popularity in Russia, while in Paris he was unknown and this anonymity, paradoxically, is what he needed to reinvigorate his work.

Eventually, he became a comfortably established regular on the Parisian art scene. But it was exactly then that he decided to return to the Soviet Union. He took that decision in 1937, just when Stalin was beginning his mass purges. It seemed a suicidal move. Falk felt his country needed both him and his art, but he was not naïve. He had an idea of the dangers awaiting him: he was expecting arrest or something similar, but his motivation to return was that museums needed his paintings. He brought suitcases full of canvases back with him to Moscow. What happened was the opposite of what he expected. By some miracle, he remained untouched by the authorities until his death in 1958. However, his art was completely ignored by the Soviet establishment. He had no income from his art and lived in poverty. However, he was accountable to no one but himself. There were no commissions or exhibitions and yet he worked tirelessly, painting for himself.

According to Falk’s widow Angelina Schekin-Krotova, his working method was laborious and lengthy: mixing colours and observing the canvas and his subject for long stretches just to place one dab in exactly the right spot and resume again with vigorous mixing.

He would often come back the following day to scrape off the previous day’s work with a palette knife. One sitter recalls her frustration that her portrait took half a year (she was 17 and restless), despite several long sittings a week. At one point, the canvas was so heavy with paint layers that it began to fall off. “The canvas covered in paint turns into an energy field,” writes Falk’s foremost scholar, Dmitry Sarabyanov.

Falk doesn’t have a distinctly recognisable trademark style that will help a novice to immediately single out his works. He could paint almost anything. His works require long almost meditative contemplation in order to reveal the canvas’s role as the ultimate intersection between a visible universe, the artist and the viewer. This viewing method was regularly practiced in Falk’s studio during his legendary weekly sessions. A small audience would secretly gather and he would show a selection of works consecutively, allowing each one to stand before the audience before ruling it was time to bring the next one out. Those privileged guests remember these sessions as pure happiness and something akin to the gathering of a secret cult. While Soviet cultural and intellectual life was being completely stifled on the surface, it bubbled all the more vigorously in small hidden pockets. One such space was Falk’s studio.

It is partly due to these showings that Falk eventually became the spiritual godfather of a whole host of Russian artists of the 1960s. However, towards the end of his life, Falk was so overwhelmed by this admiration that it became an obstacle to his work.

Falk’s name ignited a “succès de scandale” when his ‘Nude’ (1922), exhibited at Moscow’s Manege exhibition hall in 1962, earned furious criticism from the Soviet Union’s then leader, Nikita Khrushchev. The scandal re-ignited interest in Falk from Soviet underground artists of the time.

Falk chose the thorniest path, one which in his lifetime led to hardship and oblivion. It was, however, what allowed him to achieve something that eventually came to be recognised. “These poems of mine, like precious wine/ Will have their time,” wrote the poet Marina Tsvetaeva. And it seems Falk knew all along that his precious canvases would in due course be understood and appreciated.